No recovery playbook for coronavirus pandemic

We all want to know the answer to a single question: ‘When will this all end?’ The truth is there’s no recovery playbook. In fact no one has a clue.

Australians have grown used to living their life under the rudely intrusive shadow of COVID-19.

They are used to empty streets, shuttered shops and supermarket aisles stripped bare of toilet paper and pasta. They are used to tubs of hand sanitisers on the counters of the few gallant businesses that are still trading. They are used to frozen borders, stranded cruise ships and the daily bombardment of grim statistics: alarming death tolls, soaring infection rates and millions unemployed.

They have made their peace with travel bans, self-isolation, social distancing and elbow bumps instead of handshakes.

But as the complete shutdown of Australian public life nears the end of its second week, the question everyone is asking is: how much longer will this last?

“Outbreaks end with a whimper,’’ University of NSW epidemiologist and adviser to the World Health Organisation Marylouise McLaws tells Inquirer. “They end with a long tail.’’

For the first time since health authorities began removing liberties, shutting businesses, locking up the sick and the at-risk — all in the name of ridding us of COVID-19 — there are now clear signs the government is contemplating how and when to return us to “normal” life.

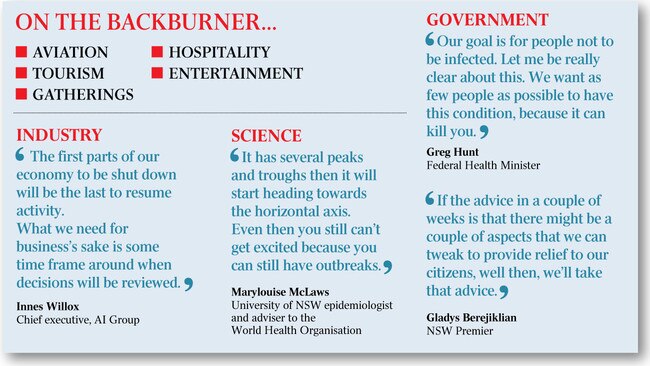

“If the advice in a couple of weeks is that there might be a couple of aspects that we can tweak to provide relief to our citizens, well then, we’ll take that advice,” NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian said on Wednesday.

Ms Berejiklian’s remarks were in response to reports that authorities were leaning towards loosening some of the operating restrictions imposed on businesses to curb the spread of the virus, but which — in the enforcing — have kneecapped the state’s economy.

Ending the lockdown

Most experts agree that lockdowns will end gradually and with extended periods of observation to see what impact, if any, the measured changes have.

“It will obviously start with things that keep society functioning but would maintain things that have high impact, like social distancing and hygiene,’’ University of Newcastle epidemiologist Craig Dalton said. “You wouldn’t have large gatherings any time soon. You would still be limiting non-essential gatherings.’’

On Tuesday, the federal government released modelling, compiled by Victoria’s Doherty Institute, that illustrated just how catastrophic the impact of an unchecked outbreak of the coronavirus in Australia would have been.

According to the modelling, an unmitigated outbreak afflicting 23 million Australians would send 35,000 people into intensive care units across the nation’s hospitals, a figure light-years beyond the ability of any country to cope.

A second scenario, in which people infected with the disease were isolated and where incoming visitors to Australia were quarantined, would require 17,000 ICU beds, still an impossible figure.

The third scenario, combining isolation, quarantine and strict social distancing, was shown to reduce demand on ICU beds to manageable levels.

A fourth option — adopting a policy of herd immunity, which would simply allow the virus to spread throughout the community until the majority of the population had contracted the illness and developed a resistance to it — had initially drawn support from some quarters when COVID-19 arrived on our shores.

But Health Minister Greg Hunt on Wednesday strongly rejected the tactic of herd immunity, insisting “our goal is for people not to be infected”.

Mr Hunt also said Australia was now facing a “different future” below the infection rate predicted in original modelling.

“We’ve rejected that because herd immunity is 60 per cent of the population on the best advice that we have. (For) 15 million people, if there is a 1 per cent loss of life, that would be a catastrophic loss of human life,” he said.

“So that’s not a theory which the Australian government or the national cabinet have been considering or proposing. We reject it.

“Our goal is for people not to be infected. Let me be really clear about this. We want as few people as possible to have this condition, because it can kill you.”

As it turns out, even the relatively mild scenario proved far worse than the experience across Australia thus far.

“In fact, the measures we put in place now have already reduced our infectivity rate much lower than the model impact of even this most significant implementation,’’ the country’s Chief Medical officer, Brendan Murphy, said.

The Doherty Institute’s modelling was theoretical, not empirical. Modelling based on Australia’s actual experience of the coronavirus is now under way. The government has promised to release it once it is complete.

But it is already clear that Australia will avoid the worst of the disease. Unless something drastic changes, we will be spared the horrific scenes witnessed in Italy, Spain and now the US and Britain, where the stricken die in hospital corridors because the ventilators needed to save them are not there.

Changing course

The frightening early trajectory of COVID-19, which saw a doubling of the number of infections across Australia every three days, has sharply altered course.

The rate of known infections is now doubling every eight to nine days. Australia has recorded just 50 coronavirus-related deaths, and fewer than 100 people with the disease are in intensive care. The overwhelming majority remain in the community, but in isolation.

Our experience of COVID-19 will be longer, slower and milder than what is happening overseas. Most importantly, it looks set to occur at a pace that will allow authorities to scale up the critical care facilities needed to treat the small number of patients mortally stricken with the virus.

“It has occurred well beyond our expectations, in the way that we have been able to bring that daily growth rate down together, and certainly ahead of what all the theoretical models would have suggested,’’ Prime Minister Scott Morrison said of the progress Australia has made.

That in itself does not mean Australians will be able to quickly resume normal lives.

Quizzed on that point on Tuesday, Dr Murphy evinced the trademark caution of all public health officials: “What we do next in Australia will very much depend on our real-time Australian data. And that’s too early to say yet.’’

A day after the government released its modelling, the Chinese city of Wuhan ended its 76-day lockdown. Wuhan was the epicentre of the coronavirus outbreak and the first of the world’s cities to go into intensive lockdown.

The city’s 11 million residents were sealed off in late January as infection rates soared, threatening to send the pandemic into an uncontrollable upward spiral that could have cost tens of millions of mainland Chinese their lives. About two-thirds of the country’s 80,000

COVID-19 infections occurred in Wuhan. Shops were closed, public transport ceased and residents were confined to their homes. No one was allowed to leave the city.

Wuhan’s journey out of that long hibernation will provide insight into how the rest of the world might do the same.

The city has been gradually easing restrictions for weeks. Although residents can now leave the city, they must first obtain government approval. They also face a 14-day isolation period when they arrive at their destination, which is long enough for the symptoms of coronavirus to manifest and run their course.

Authorities will be watching closely to see how the gradual easing of restrictions affects the city’s infection rate. Their mortal fear is that even a gradual easing of restrictions will unleash a second wave of infections.

Mr Hunt told The Weekend Australian last Saturday, a staged reopening of society was a “very realistic assessment’’.

A slow road

For the business community, this liberalisation cannot occur soon enough. The head of the Australian Industry Group, Innes Willox, said the pandemic would shave between 4.5 and 5 per cent off Australia’s trillion-dollar economy and send unemployment skyrocketing to between 10 and 15 per cent. Furthermore, he said that whereas the shock to the economy was brutal and sudden, the recovery would be painful and slow.

“The first parts of our economy to be shut down will be the last to resume activity, as they largely involve significant public contact,’’ he told Inquirer. “Aviation, tourism, hospitality and entertainment — they’ll be the last to come back.’’

Mr Willox acknowledged the pandemic was predominantly a public health issue. But he said the time had come to give business some guide as to when things would liberalise.

“What we need for the sake of business is some time frame around when decisions will be reviewed or actioned,’’ he said.

“At the moment, there is not much on the horizon for business to review or look forward to.’’

For all the talk of curve-flattening, Professor McLaws said Australians should not expect a neat end to the pandemic.

She said the bell-curve beloved by the media, one that showed a sharp increase in cases, then a plateau, then an equally sharp decline, rarely occurred in practice.

“It has several peaks and troughs, then it will start heading towards the horizontal axis. Even then, you still can’t get excited because you can still have outbreaks,’’ she said.

This can go on for years.

The Spanish influenza pandemic ran from 1918 to the northern summer of 1919. By the time it had run its course it had killed between 20 million and 50 million people and infected 500 million, a third of the world’s population at the time. A second wave of infection killed more American victims than the initial outbreak.

The debate occurring about when and how to return to normal life is not confined to Australia. It is occurring all over the world. French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe said the question about when and how to end the lockdown was impossible to answer definitively because the situation was without precedent.

“We have never confined such a large number of people, and by definition we have never relaxed confinement of such a large number of people. There is no written process or tried method.”

As well as easing restrictions by sector, Australia may see any relaxation occur geographically or unevenly across the population.

Hot spots, where the infection is known to be more widespread, may have to wait longer for businesses to reopen and mass gatherings, such as sporting events, to be allowed.

The elderly and the vulnerable may also be encouraged to remain in isolation longer, while younger and fitter members of society resume their normal working lives.

If there is to be a definitive end to the pandemic, it will come with the development of a vaccine.

That, however, could be as much as 18 months away. In that time, rich countries are likely to have contained the disease. In the developing world, however, coronavirus threatens to be a deadly juggernaut.

“I think it could be one of the greatest public health disasters in history,’’ Dr Dalton said.

Australia is not immune from this. An eruption of the disease in the southern hemisphere will have a profound impact on the ease with which we trade with and travel through the developing world.

“There’s no playbook for this pandemic,’’ Dr Dalton said. “It is totally new. Every government is learning as they go.’’

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout