No more treasure in trash

Changes in the world’s rubbish industry are being felt at the very bottom of society.

Across India, from poor villages to expensive residential areas of cities, millions of garbage pickers are at work to collect what other people dispose of. They are called raddiwalas, ragpickers, scavengers and waste managers. Some go door-to-door, others gather iron and used bricks on construction sites, still others clean parks and city streets. There are even specialists who gather hair, which is exported in bulk for wigs.

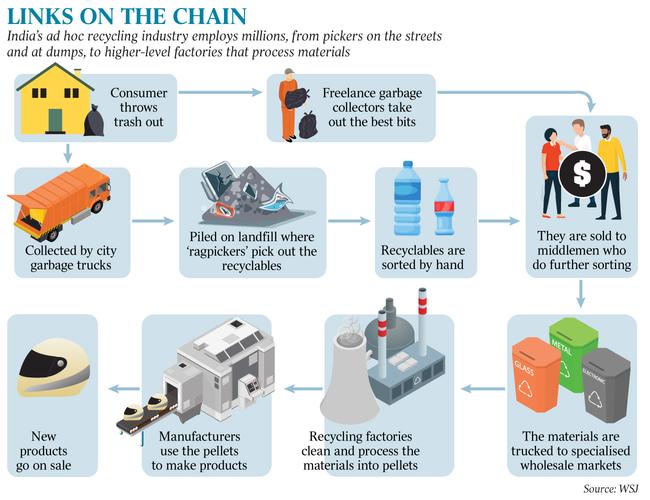

They’re the starting point of a multi-layered, $US25 billion ($36bn) industry in India that advances through increasingly specialised middlemen and industrialists to eventually turn garbage into new objects. The work is a moneymaker for conglomerates, as well as a route out of poverty for some of India’s poorest people.

All of that has been upended by a crash in a global garbage market dominated by two players: China, which buys most of the world’s garbage, and the US, which sells the most.

Last year, China dramatically cut the amount of garbage it buys. The reduced demand from China and continued supply from the US flooded the world garbage market and drove down the price of rubbish everywhere.

Indian recycling companies took advantage of the deep discounts and started importing more garbage from the US and elsewhere. The imports of mixed scrap plastic to India rose by 33 per cent last year.

Garbage migration

The jump in supply pushed prices down for the low-end Indian workers who pick through mountains of locally produced garbage for raw materials to sell.

That’s affecting an Indian rubbish economy powerful enough to have prompted its own migration pattern: thousands of families left their rural villages to collect garbage in cities. Now, with their garbage hauls worth less, many are returning home.

For the pickers, the going price for a kilogram of plastic water bottles, which used to bring in about 45 rupees (95c) is now worth only about 25 rupees.

The garbage glut also lowered profits for industrial recycling companies that turn the rubbish into usable materials. Plastic pellets, the end-product after processing some plastic scrap, went from 80 rupees to 45 rupees per kilogram.

Malaysia and other countries have also had a surge in plastic scrap imports, while India and Indonesia are among the top destinations for paper.

“A lot of people came into this industry” in India and around the world when demand and prices were high thanks to China, says Adam Minter, author of Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade, a book about the rise of the recycling industry. “Now they are having to get out.”

China ratcheted up restrictions on imports of recyclable materials to force its recycling industry to absorb more of the waste generated in the country. Beijing is also nudging the country away from the role of taking others’ garbage, which is viewed as a dirty industry.

In the US — the world’s top exporter of garbage — paper and plastic scrap exports to China tumbled by more than 30 per cent last year.

Garbage mountain

The global garbage glut means India’s own rubbish is worth less to its domestic recyclers. After a consumer throws out his garbage, an early link in the rubbish chain are people such as Ambia Khatoon, who with her family scraped out a living for 15 years by scavenging at the Ghazipur landfill, a 60m-high mountain of trash on the outskirts of New Delhi.

The family pulled in more than $7 a day, enough to support seven children and to buy the land where they lived next to the landfill.

Ghazipur landfill is one of multiple mountains of garbage around Delhi which have grown for years, climbing higher and higher as hundreds of trucks per day dump the megacity’s waste. It can be seen for kilometres, a towering grey plateau with a flying halo of thousands of scavenger birds circling above.

Men climbed the heap to bring back bags full of scrap material, while women and children sorted the pickings. Worthwhile items included plastic bottles, bicycle rims, cardboard boxes, rubber sandals, copper wires and toothpaste tubes. Even old pieces of bread and rice could be sold to feed the cows of a nearby dairy.

Last year’s price upheaval cut their earnings to less than $4.30 a day, forcing Khatoon, 46, and her youngest child to move home to their rural village.

“The prices have never declined so much,” she says. “Everything fell. Aluminium, brass, steel, paper, food waste, even hair.”

The pickers sell to middlemen, who collect and sort the scrap for sale. They say they often have to sell at a loss now, so are buying less and holding on to inventory, hoping for prices to bounce back.

Mohammad Nasir used to move a truckload of recycled plastic each week to buyers, but now he sells a truckload every three months.

“My wife asked me to go buy food,” he says, pulling a long grocery list from his pocket. “But I don’t have the money.”

The next layer — recycled waste can go through 10 or more middlemen before it is reprocessed into something usable — has the same problem. Ninety minutes’ drive from the Ghazipur landfill is the Tikri wholesale plastic market, an open field with hectares and hectares of scrap divided into piles — car bumpers, syringes, plastic bottles, old desktop phones, even bags filled just with twist caps.

Price plummet

Scrap wholesaler Kush Chauhan says he has been buying and selling much less as demand and prices have tumbled.

“If this plastic doesn’t sell, it will be bad for the environment,” because it will have to be burned or thrown back into the landfill, he says. Specialists in different types of plastic buy in bulk at the Tikri market and then further separate, clean, shred and melt it.

Kunal Panwar, a regular buyer, specialises in pens. He buys tons of them, which are cleaned, bleached and chipped. A group of women sorts through large piles of shard and picks out the remaining caps and other parts which are made of a different type of plastic.

“A lot of (scrap) imports have started coming in,” but only to certain ports and markets, he says. “Those with connections know how to get it.”

Big recycling companies gathered at a conference in Kochi in southern India in February discussed lower prices and the search for new buyers.

“We are now swamped” with too much scrap, says Ranjit Baxi, head of J&H Sales International, a British recycling company, and president of the Bureau of International Recycling, an industry association.

“Outside China, we need to create a demand.”

Pramod Agarwal, chairman of Rama Paper Mills in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, has been filling his warehouses with mixed paper from the US, which he uses to make newsprint and cardboard. The imports were cheaper than what he could buy in India and also better quality, meaning fewer non-paper items were mixed in.

“Everyone wanted to take advantage of the price fall” and bought more, he says.

The slum where Khatoon and her family lived on the edges of the Ghazipur dump is surrounded by 3m-high piles of scrap, sorted into different types — aluminium foil, rubber tubing and pens — which is then stuffed and sewn into bulging white plastic bags.

Life during scrap boom

Khatoon was one of the millions of people who rode the scrap boom at the start of the century. She arrived in 2003 with three bags and six children, to join her husband in the search for a better life.

She started working on the rubbish mountain. Her three youngest children came with her — one on her back, one by the hand and her eldest following behind. “It was very difficult at first,” she says. “I kept fainting and throwing up.”

Other times she would leave her children nearby and chase the trucks as they dumped tonnes of garbage. She learned what to take (brass and aluminium foil were among the most valuable) and what to leave (glass bottles usually aren’t worth the trouble). She would search for broken toys for her children to play with.

Khatoon often didn’t eat, so as to have enough to feed everyone else. But India’s rapidly expanding middle class was spending like never before and throwing out a record amount of rubbish. As the mountain grew, so did the value of the things she found on it. And global prices for scrap were soaring, thanks to demand from China.

Her slum swelled to more than 500 families. Rents rose and shops and little eateries opened to serve the waste workers.

Their homes were a patchwork of scavenged materials, part bamboo, part old doors, part corrugated steel, all wrapped in layers of tarp and the remains of plastic billboards. The city connected the slum to electricity and water. Most huts had televisions and satellite dishes.

The type of trash evolved as more Indians could afford more stuff. Water bottles appeared, along with shopping bags, clothes, cardboard and motorcycle helmets. The latest tech — first piles of cassette tapes, then CDs and DVDs — started showing up. And mobile phones, smartphones and all their accessories.

As the mountain grew, it became more exhausting to reach the peak, where the new stuff was dumped. The 10-minute trek grew to 20 minutes. During the hot, dry summers, when temperatures top 43C, pickers lugged litres of water to stay hydrated. Methane fires sprouted up across the mountain, lighting up the night.

After China’s shift

China’s change in policy, and the drop in prices, had a sharp effect on the slum.

Workers are now struggling to avoid plummeting deep below the poverty line. Almost one in five families has left. Others have turned to day labour, pedalling bicycle rickshaws or cleaning the meat market.

Khatoon’s family has had to sell jewellery and put off doctor visits. Her husband and sons get occasional day labour jobs but don’t make the same amount they made off scrap.

At breaking point, Khatoon and her youngest child moved back to their village, to a mud and bamboo hut that has been unused for 15 years. It leaks when it rains and only gets power for a couple of hours a day.

Khatoon says she misses the materials available at the landfill. She could use more plastic sheets to stop the leaking and she would cut used shower curtains to create windows and bring in light.

There is no work, so they wait for money from the family remaining in New Delhi. An eye injury Khatoon received from being hit on the garbage heap by the swinging back flap of a truck is acting up, but she can’t go to the doctor.

Her daughter is 16, nearing marriage age, but the family can’t afford it. They couldn’t celebrate Eid al-Fitr this year, marking the end of Ramadan.

Khatoon says she would prefer that her 10 grandchildren didn’t have to suffer village life.

“We want them to grow up in the city, even if it is in the slums,” she says. “I’d go back if the scrap prices were better. It is the only job that I know.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout