No country for old men holding back the future of East Timor

Historic political rivalries plague East Timor’s attempts to establish its new energy economy.

Virgilio Guterres knew he had little chance of success when he tossed his hat into the ring last month for East Timor’s presidential contest but the head of the country’s press council could not bear another election where the same old faces touting the same old revolutionary credentials once again wrestled among themselves for power.

At 56, and a former student revolutionary himself who spent 2½ years in a Jakarta jail for his political activities, Guterres is no spring chicken.

But in one of the world’s youngest countries – with a median age of 18 – he is still considered junior to the ranks of mostly septuagenarian former resistance fighters who have held tight to the reins of government since the country won a long and bloody struggle for independence from Indonesia in 2002.

“I stood up to send a message to the old leaders, and also the people of this country, that the new generation are here and we are ready to take responsibility for this country,” Guterres told Inquirer.

“It’s been 20 years since independence, 15 years since this country started to enjoy the proceeds of oil, but look at the state of our health, education and agricultural sectors. More than 80 per cent of our people rely on agriculture yet the budget for agriculture is less than 2 per cent. The budget for education is less than 10 per cent. Youth unemployment and youth illiteracy are very high. Where does the money go?

“I respect the old leaders but they are not focusing on the people’s wellbeing. Most people feel independence is something that only happens in Dili.”

When first-round votes were tallied, Guterres – a respected local figure who ran as an independent with donations from friends – attracted a tiny fraction of the 664,000 votes cast. But along with several other younger candidates, he has helped amplify a conversation about the need for political renewal, and for a new generation of leaders less interested in past glories than in building a glorious future.

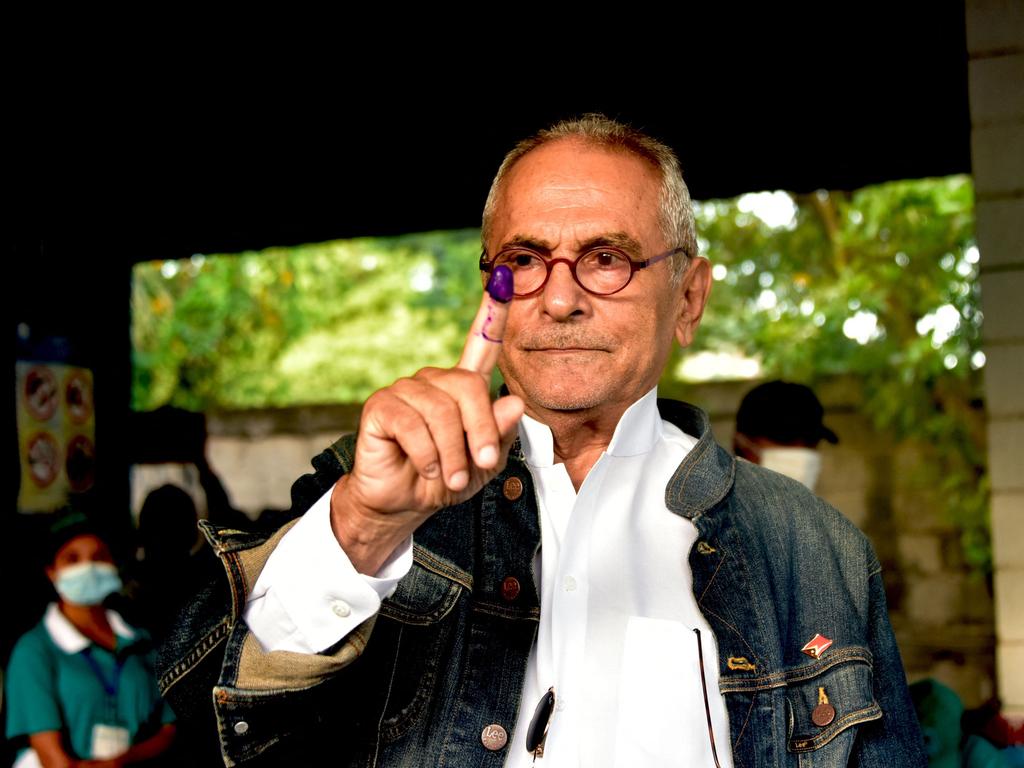

In the end, the contest predictably came down to two old war horses; incumbent President Francisco “Lu Olo” Guterres, 67, from resistance-era political party Fretilin (the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor) and East Timor’s second president and Nobel Peace prize laureate Jose Ramos Horta.

Ramos Horta was ultimately declared the victor last week after a run-off in which political rivalries dominated the debate while the country’s 41.8 per cent poverty rate, 12.3 per cent youth unemployment and striking disparity in urban and rural living standards barely rated a mention. The 72-year-old will be inaugurated into office on May 20, the 20th anniversary of Timor-Leste’s freedom from Indonesia.

Ramos Horta – whose campaign was backed by East Timor’s father of independence, first president and fourth prime minister Xanana Gusmao – has since addressed concerns over political instability in the country, assuring the population he will work to heal divisions between political leaders. “I will do what I have always done throughout my life ... I will always pursue dialogue, patiently, relentlessly, to find common ground to find solutions to the challenges this country faces.”

But even Ramos Horta, with his famed diplomatic skills, faces an uphill challenge to heal the acrimony between old revolutionaries and their conflicting views on how to ensure a sustainable economic future for East Timor.

Gusmao, 75, who leads the CNRT (National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction) party that left the ruling coalition in 2020 over allegations the former president misused his power, backed Ramos Horta’s bid in the expectation he in turn would support his push for a dissolution of parliament and early general elections.

The CNRT’s walkout forced the government’s collapse and the resignation of Prime Minister Taur Matan Ruak, who stayed on as head of a new coalition comprising his People’s Liberation Party, rural party Khunto and Fretilin to steer the country through the coronavirus pandemic.

But Gusmao says the Ruak government is illegitimate and wants to return as PM to pursue his pet Tasi Mane oil and gas project, which would involve building a pipeline from the Greater Sunrise oil and gas field in the Timor Sea to a proposed $15bn processing plant and associated infrastructure on the south coast of the island. The government put the controversial project on hold over concerns about investing so much of the country’s dwindling sovereign oil fund on a finite resource that would not generate sufficient jobs, though there has been talk of seeking Chinese investment.

The Greater Sunrise field, with an estimated 5.1 trillion cubic feet of gas and 226 million barrels of oil condensate, lies 450km northwest of Darwin and 150km south of East Timor. A production-sharing agreement is still pending between Australia and Timor.

Meg O’Neill, chief executive of Woodside Petroleum, which owns a 33 per cent stake in the field, this month called for “serious consideration” to be given to kickstarting the project amid global energy shortages triggered by sanctions on Russia over its Ukraine invasion. Woodside, however, remains adamant Tasi Mane does not stack up.

Virgilio Guterres, too, is part of a growing band of Tasi Mane sceptics who worry the government is gambling the country’s future on a project with no guarantee of “social and economic return for the people”. “I’m not against big projects. We have the right to dream high, but what I don’t agree with is this idea that we must sacrifice a whole generation of society for the wellbeing of the next,” he says.

He also takes issue with the continued privileges afforded independence veterans and former combatants by the state, given the “fight for independence in this country was a collective struggle”. “This is the last chance for this older generation to restore their image by doing good things now for the wellbeing of this country,” he adds.

Michael Leach, an East Timor political analyst and Swinburne University professor, says the current crop of leaders has benefited both from a traditional Timorese reverence for elders and their resistance legacy, though this month’s presidential poll and parliamentary elections due next year will likely be the last terms for many given their advanced age.

“So the question is, what are they doing to bring through younger leaders and prepare them? This is a big five years for transition and a lot of policy changes that need to be made,” Leach says. “The big one is how to diversify the economy beyond oil and gas, which, no matter whether Greater Sunrise goes ahead or not, needs to happen.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout