Nixon’s trip to China opened the door to a quarter of humanity

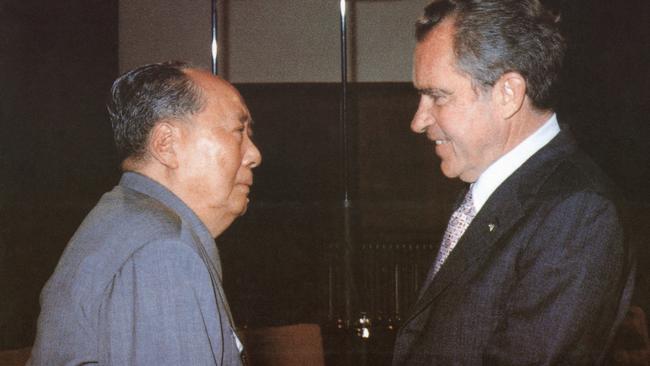

President Nixon’s famous meeting with Chairman Mao was a curious affair that decided nothing – but it still changed the course of world history.

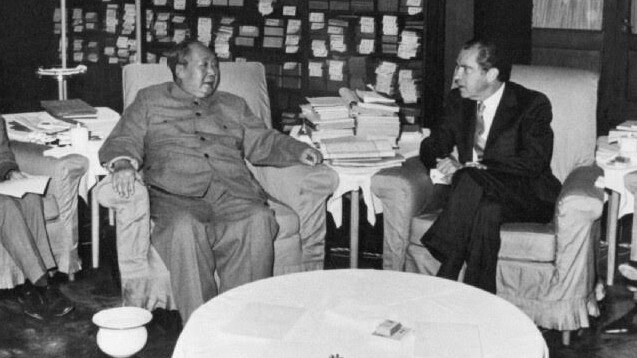

The three leaders who gathered that day were among the most influential on the planet. But their time was running out, their years of power slipping beyond the twilight. At the Great Hall of the People, on the western edge of Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, on February 21, 1972, sat US president Richard Nixon, Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, Mao’s premier since 1949.

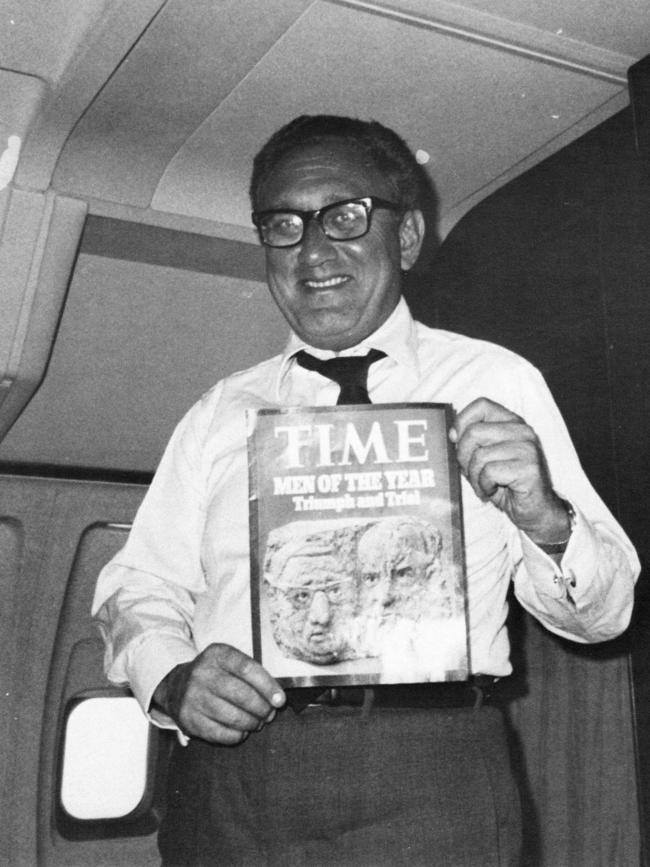

With them was Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger. The seventh person to bear that title – and to become the most dominant – had worked towards this gathering for years.

Nixon had raised the relationship with China with Kissinger on his first day in the White House in January 1969. The president had written about it in The Economist and Foreign Affairs magazines in the lead-up to his November 1968 election victory: the US could not ignore a quarter of the world’s population even if it remained purposely in angry isolation.

Nixon hated communists. There were too many of them. Those in the Soviet Union had nuclear missiles aimed at American cities. Not as many as Nixon’s America had aimed at them, but the threat was real. And the communists were pulling strings in a costly proxy war between communism and the West over Vietnam.

Nixon’s relationship with that war was complex. He had campaigned with a plan to end it, then in office ramped it up in an unprecedented manner. He didn’t plan on being the first US president to lose a war.

After a church service on Sunday, March 16, 1969, the president, irate at rocket attacks directly on Saigon, signed off on B52 bombing raids on North Vietnamese Army camps in neighbouring Cambodia. Engaging a third country, whose civilian deaths reportedly reached 4000 within days and later topped 100,000, was a roll of the dice. With Nixon, the risk-taking gene had always been dominant.

The unwieldy-looking eight-engine B52s, named after the year they first flew, had a 56m wingspan that gave them the appearance of lumbering pterodactyls. They were anything but; with a top speed of 1046km/h they could drop 32,000kg of bombs in short order. Sixty of them set off that evening, 48 turning left for the secret mission. Nixon’s chief-of-staff, HR Haldeman, wrote in his diary that the following day Kissinger “came beaming in with the report (of the damage), very productive”.

In 1973, Kissinger would share the Nobel Peace Prize after signing the Paris Peace Accords designed to settle the conflict. All sides ignored them. Another 11,780 US troops would die in Vietnam in Nixon’s first year as president. Peace was years off.

In 1972 Nixon, then 59, was enjoying the triumphs of the space race; eight Americans had walked on the moon by the time he sat down in the Great Hall. Another four would that year. The US economy was fine, with the Arab oil price shocks and runaway inflation more than a year away.

Mao was untouchable as CCP chairman, even at 78. He had emerged as a clever, inquisitive student of political thought in the first decades of the 20th century as turmoil gripped China in the fading years of the Qing dynasty.

He read Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, obviously, but only after having consumed the ideas of liberal-thought pioneers John Stuart Mill and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He led various rebellious lives in those volatile times and seemed torn between the need for civil liberties and a revolutionary desire to up-end them all. But in a land of numberless peasants he realised their dormant power and sided with the communists, whom he soon led. The Long March secured his and Zhou’s authority in the Communist Party despite it being a circuitous retreat. And twice before the march, and again at its start, he had children with third wife He Zizhen that they passed on to others and who were lost forever. Mao seemed untroubled.

His rise to head of the Communist Party, the end of the civil war and the defeat of Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang – pushed off to Taiwan, where a wealthy robust democracy now flowers, annoying Chinese communists to this day – had secured his place in history long before he killed political opponents to cement it.

His first Five-Year Plan brought about rapid industrialisation of the country but poorer agricultural output from collectivised farms. Dissenting voices were flushed out in clever strategies such as the Hundred Flowers Campaign that encouraged critical feedback on the communists’ programs. Those who spoke up were persecuted to the point of suicide or shot. The second Five-Year Plan diverted more farmers away to infrastructure projects and those who remained falsified their production quotas to avoid punishment. Along with some bad weather this led to China’s Great Famine, perhaps the worst man-made disaster in history, leading to the deaths of up to 55 million. As with the children Mao had given away, he moved on, but not before ordering stocktakes of the “hidden” produce he believed rural villagers had stored. These “enemies of the people” were beaten to death.

Mao’s vicious streak manifested itself in bloody purges of his enemies, the luckiest of whom were sent to labour camps and died there. Then, following Joseph Stalin’s death, China split from the Soviet Union and lost aid and technical support. Mao’s response was the 10-year Cultural Revolution in which he encouraged young communists to endless rebellion. Teachers, scientists and intellectuals were sent to work in rural areas. The less fortunate were murdered or took their own lives. The so-called Gang of Four emerged in this year, led by Mao’s volatile and cruel last wife Jiang Qing.

As Kissinger approaches his centenary next year, his reputation ranges from being acclaimed as a genius of groundbreaking diplomacy to enduring charges that he is a war criminal. He has written a dozen books to straighten the record, but kinks remain.

His family fled the Holocaust for New York in 1938. He was academically gifted, but his studies were interrupted by war service during which he fought against the country of his birth at the Battle of the Bulge. He completed a degree in political science at Harvard, held a series of academic posts and co-founded the Centre for International Affairs while giving foreign affairs policy advice to Nelson Rockefeller’s three shots at the Republican presidential nomination.

When Rockefeller failed again in 1968, Kissinger, who had said Nixon was a dangerous man, offered to join the new leader’s team. Nixon had met Kissinger and had been impressed and appointed him national security adviser. Kissinger was immediately surprised by the latitude he was given. He found it curious the president would take instruction from a pushy German (his accent remained strong) given the trouble caused by bossy Germans in the first half of the century.

And, like Nixon, Kissinger was a risk-taker; his “official” trip to see Pakistan’s president Yahya Khan in 1971 involved him feigning illness and “resting” in Islamabad while taking Khan’s plane to Beijing on a secret mission to meet Zhou, with whom he had been covertly communicating for a year. In any case, Khan was busy at the time completing his Bangladesh genocide in which up to three million people would be murdered.

Nixon rated Kissinger highly, as did the US president’s successor Gerald Ford, who had delivered lectures at Kissinger’s Harvard seminars. In 1974, a shattered Nixon’s sole advice for the incoming president Ford was to keep Kissinger on: “Henry is a genius, but you don’t have to accept everything that he recommends. You can’t let him have a totally free hand … there are times when he has to be kicked in the nuts.”

Zhou had not been born to peasantry and received a solid education, learnt English and studied for a while in Japan. Back in China he became radicalised, and while studying further in France he formed a European branch of the Chinese Communist Party. On his return the beginnings of what would become the protracted Chinese civil war disjointedly unfolded. During these tumultuous years he would encounter Mao and they would form a partnership that would last their lives, they alone surviving the bloody internal conflicts that distinguish Chinese communism. Zhou remained an obedient servant. In the Bible, God asks Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac but calls it off; in 1968 Zhou was similarly tested.

Mao’s wife had Zhou’s daughter Sun Weishi – a beautiful actor turned acclaimed theatre director – arrested. Jiang knew her from her own days as an actor and was envious. She made Zhou sign the arrest warrant. She had Sun moved from one jail to another where she was raped and tortured. Jiang reportedly taunted Zhou delivering to him a letter Sun had written seeking his help. He didn’t. Neither did Mao. After seven months Sun died.

By very different means these four men had risen to the apex of very different countries and cultures. Were it not for the presence of Mao and Zhou you might believe they were united in a common humanity. But they shared only interests, chiefly a fear of and hostility towards the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, the Russians supplied food, vehicles and weapons to the North Vietnamese Army by boats that unloaded all this at Chinese ports. It was then mostly sent on trains headed south, along with China’s military aid – and 300,000 troops.

Above all else, Nixon wanted to discuss these issues with Mao – and Mao with him – but their techniques would differ and everything was on Mao’s terms.

The Americans arrived in Beijing at 11.30am on a Monday. Zhou was there to meet them, but there were no crowds. Beijingers had been warned to go about their business and ignore the visitors. A motorcade headed for the city. A woman who waved at it was detained. She had spotted a young relative – an interpreter – in one of the cars. They arrived soon after at the Taio Yu Tai guesthouse where most important visitors stayed. The Nixons may well have slept in the bed Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara did a few years before.

That night’s capital city news reported on the arrival in a brief, last moment on the bulletin.

It had not been confirmed that Nixon would meet Mao, but as soon as they arrived Mao contacted Zhou and said he wanted to see the US president at 2.50pm. Mao had been ill for months and unconscious for most of the past fortnight. A chain smoker, he had lung and heart problems. He’d almost died of pneumonia weeks before. Doctors reportedly used the oxygen tanks US security had sent on ahead in case Nixon fell ill to keep the chairman alive. Mao shaved for the first time in a month and donned a new Mao suit and new shoes. His doctor stood by the door.

The two teams entered Mao’s book-lined Great Hall study. There were upbeat introductions and the leaders shook hands, Mao holding on to the president for more than a minute. “I voted for you,” Mao said with a smile, his words being interpreted by a member of his staff, American-born Tang Wensheng, who was familiar with her boss’s Hunan accent and newly slurred speech. The exchanges were awkwardly delayed as she interpreted each leader’s words. As a result the encounter ran over time yet Mao and Nixon spoke a mere 2266 words between them in 55 minutes.

Nixon raised issues including Taiwan, Japan, Russia and North Korea. There would be no specifics, no conclusions, no arguments. But everyone understood the power of what it meant. Nixon had said he wished to “nudge history”, and they did, leaving history to deal with the details. And just in time. Within four months there would be a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate building in Washington that eventually would sink Nixon’s presidency. By that December Zhou would be stricken with bladder cancer, and Mao would refuse him treatment until it was too late. Mao died just months after Zhou’s death in 1976.

Nixon commented later: “You have to divide the politicians of the world into poets and pragmatists. Zhou Enlai is part poet, part pragmatist; he has the surest grasp on the great issues of the world of any man I’ve met. But Mao is all poet. Maybe a revolutionary leader has to be a poet, he must be a dreamer. That’s his strength.”

When Nixon and Mao met, Americans were earning about $US16,700 a year, the average Chinese about 35c a day. China’s share of the world economy was about 1 per cent while the US enjoyed almost 25 per cent. Today China has 18.7 per cent of the world economy and the US 15.9 per cent.

“The second half of the 20th century, in geopolitical terms, divides itself into the period prior to Nixon meeting Mao and the period after. It completely changed the dynamic of the Cold War,” says former senator Stephen Loosley, a senior fellow at the US Studies Centre. “It led directly to China becoming a global player. It was the most consequential bridge-building of the 20th century.”

John Lee, a former senior adviser to the Australian foreign minister, agrees: “These four characters arguably did more to shape great-power politics for the next half century than anyone else from their generation.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout