Next-gen vaccines to help change direction of war on Covid

Next-generation jabs are already being developed as medical scientists strive to keep pace with a changing virus.

But the medical scientists driving a second wave of vaccines want to recast pandemic management to reflect how the next-generation immunisers will work.

With Victoria joining NSW, Tasmania and the ACT in reaching the double-vax threshold to open up, allowing Melbourne to at last emerge from lockdown on Friday, and their single-dose rates approaching or exceeding 90 per cent of over-16s, the research effort shows no sign of slowing.

Far from it. Australia’s world-ranked Covid researchers are working to develop new ways to deal with the virus at the pace it continues to change.

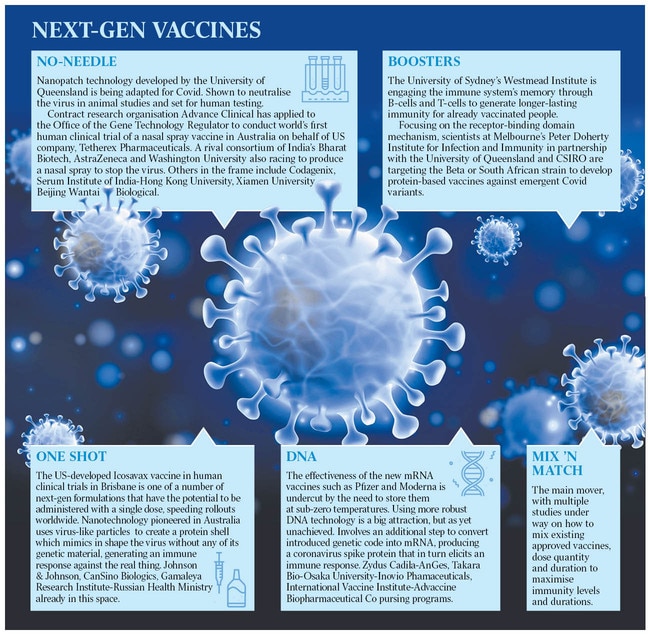

The innovations include needle-free vaccine delivery, variant-specific shots, long-lived boosters and a combination preventer for seasonal infections such as influenza. Some are now being tested in Australian human trials.

The aim is to make the 2.0 vaccines easier to handle and use, cheaper, and more attuned to future iterations of the virus, the lab gurus say. “We are not talking about reinventing the wheel because we have really come an extraordinary way since the start of 2020 in terms of taking something from scratch and getting it safely into people’s arms,” says Sharon Lewin of Melbourne’s Doherty Institute, where three next-gen vaccines are in the pipeline.

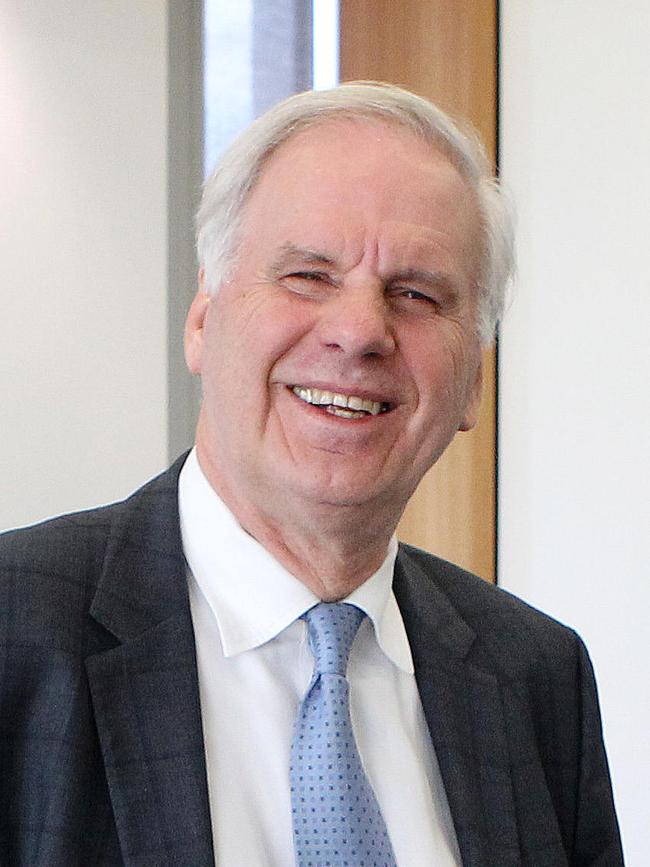

Tony Cunningham, director of the Centre for Virus Research at the University of Sydney’s Westmead Institute, tells Inquirer: “I think duration of immunity and new variants are the two main issues we will be grappling with. That means there will be a need for boosters and a whole lot of questions about who gets them, when, and using which of the vaccines we have available.”

Both the Australian Medical Association and the Labor Party back the establishment of a federal, epidemic-focused agency modelled on the US Centres for Disease Control – though this approach is by no means universally supported by the researchers. Lewin questions the need when Australia already has a deeply integrated public health system.

“What we don’t have is a good link between the research, public health system and industry to inform the public health response,” the Doherty director says. “In my view, we need to strengthen the research network across Australia in closely aligned partnerships with industry and government to develop things like vaccines and therapeutics and integrate them all with the public response. I don’t think you want to have everyone employed by a state or federal government”.

Cunningham argues for a national “biobank” to act as a knowledge exchange among researchers. The prototype Vaccine, Infection and Immunity Collaborative Research Group in NSW, set up with seed money from the state government, could be built on “so that the brightest ideas can plug into resources quickly and be utilised”, the veteran virologist and professor of medicine says.

On the other hand, University of Queensland scientist Trent Munro, whose molecular clamp team went tantalisingly close last year to an Australian-made Covid jab, insists a stand-alone pandemic agency is worth pursuing, provided it reflects the “unique features” of Australian healthcare.

“A CDC-like model absolutely should happen here,” he says.

“We’ve seen disparate data sources that have really caused us to struggle … there would be immense advantages to a central body that could respond and also bring information together.”

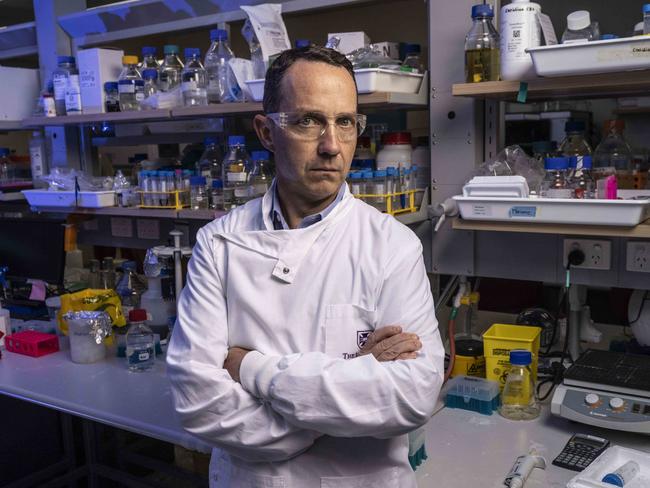

Munro knows all about the need to think fast and be nimble to keep pace with the virus. Since the molecular clamp vaccine stumbled at a technical hurdle – a formulation glitch produced false negative readings to HIV in a clinical trial, unrelated to performance or safety – the team has gone back to the drawing board. Clamp 2.0 will likely have in-built flexibility to be redirected at individual future variants as they emerge.

“The other part will be having vaccines that are more suited to quick, large-scale production and that are also easier to distribute,” Munro says. “What we need to identify is vaccine platforms that can be transported globally and given in difficult places … challenging geographies such as villages in Africa. Then you come to dosing. What we’re learning is that we haven’t fully fleshed out what is the ideal dosing regimen for longer-term protection.

“Most of the vaccines are still currently a two-dose course, with some recommendations of a third dose for high-risk or elderly populations. That puts huge pressure on production,” he says.

“Instead of thinking, say, 12 billion doses globally over a 12 to 24-month period, it is suddenly 18 billion does with boosters.”

Remember, the mRNA technology used in the in-demand Pfizer and Moderna vaccines now underpinning the rollout in Australia did not exist in working form before the virus erupted in central China in the winter of 2019-20.

Protein-based platforms such as the molecular clamp are also cutting edge, although that is easily overlooked in the headlong research and development stampede.

Among the next-gen vaccines being trialled here is a versatile offering from Seattle-based biotech company Icosavax, designed also to go after new strains. Using nanotechnology developed by former Australian of the Year Ian Frazer and the late Jian Zhou for their breakthrough cervical cancer vaccine, a synthetic “virus-like particle” is injected into cells to mimic the shape of SARS-CoV-2 and generate a powerful immune response against it.

Safety and preliminary efficacy testing of the Icosavax candidate vaccine by the University of the Sunshine Coast is in full swing north of Brisbane, involving 168 people aged 18 to 69. USC Clinical Trials Director Lucas Litewka says the formulation could also have application for influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, suggesting potential for cross-use were it to progress. “I think the benefit here is that we’re using an existing technology to apply to the Covid setting,” he says.

Worldwide, eight Covid-19 vaccines have been approved for full use, with the trio being rolled out in Australia – Pfizer, Moderna and locally made AstraZeneca – dominating supply, along with a soon-to-arrive Novavax jab.

Johnson & Johnson’s one-shot formulation, though provisionally approved by Australia’s medicines regulator, is unlikely to be imported given its similarity to AZ and side effects of rare but serious blood clotting.

Nearly 300 vaccines are still in development, according to the World Health Organisation.

While most are designed to generate an antibody reaction that can wane after six months, Cunningham’s team in Sydney is exploring how to trip the immune system’s “memory bank” of T-cells and B-cells to elicit eight or more years of protection.

“There are a few ways to skin a cat here,” he says.

Local nanopatch technology being adapted as a no-needle Covid vaccine by another UQ researcher, David Muller, has neutralised the virus in animal studies and is on track to enter human trials. “We’re working at the moment to put Delta on the patch,” he says.

Separately, contract research organisation Advance Clinical has applied to the Office of the Gene Technology Regulator to conduct the world’s first human clinical trial of a nasal spray vaccine in Australia on behalf of US company Tetherex Pharmaceuticals.

As Lewin argues, mix-and-match protocols involving existing vaccines may be a cost-effective way forward, maximising bang for the buck of the untold billions of dollars pumped into the international R&D effort to date.

In the US, regulator the Food and Drug Administration this week moved to allow people to receive as a booster a different brand of vaccine to the one they initially received.

This came on the back of research presented to an expert committee advising the FDA that recipients of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine who had a top-up dose of Moderna benefited from an astonishing 75-fold increase in their antibody levels. This compared to a fourfold increase for the J&J recipients who received an additional dose of the one-shot vaccine as a booster.

While the researchers warned they were not endorsing one combination over another, Amanda Cohn of the CDC told The New York Times: “From a public health perspective, there’s a clear need in some situations for individuals to receive a different vaccine.”

Circling back to her argument for a more cohesive research response, Lewin sees a “lot of upside” to mix-and-match and also to improving the vaccines that we already have. “I think we will see some interesting advances, basically synthesising the current vaccines to make them cheaper and less immunogenic,” she says.

Cunningham says: “We’ve rushed into what is the low-hanging fruit on vaccines, which is neutralising antibodies, and I think increasingly we will be looking at alternatives to do specific things or to address specific manifestations of the virus.”

No one vaguely sensible believes that Australia is done with Covid-19 now that the immunisation rate has hit 70 per cent nationally and pacesetting jurisdictions are zeroing in on helping nearly all of those who can or want to be protected.