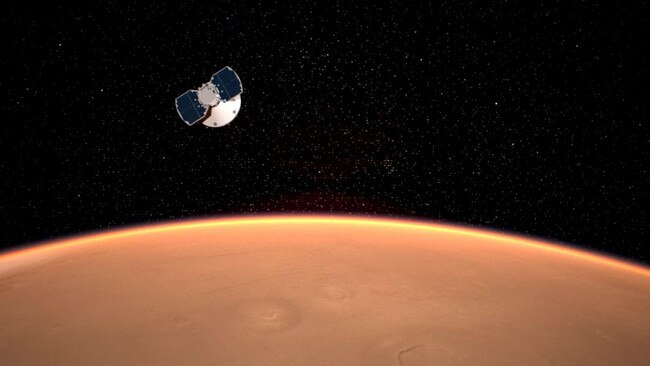

Next giant leap to Mars

The 50th anniversary of Apollo 11’s moon landing has revived ambitions for return journeys — and the next target, Mars.

The weekend 50th anniversary of Apollo 11’s moon landing has revived ambitions for return journeys — and the next target, Mars.

The US, China, Russia, India, Israel, Japan and private businesses are staring into space with dreams of building colonies on other worlds. But a human presence on the moon remains crucial to these visions.

In the 1960s the motive for the US and the Soviet Union venturing to the moon was national pride — to win the space race. Nowadays, we still look to the heavens hoping to show off our nation’s technological capability, but we’re also conscious of blasting into contention for the multibillion-dollar industries that space opens up — creating technology to mine the resources beyond Earth.

And there are the scientific achievements in learning what other celestial bodies can tell us about the universe, our planetary history and our own origin.

For the US, there are the twin imperatives of science and politics. President Donald Trump wants the US back on the moon by 2024, at the end of what would be his second term.

This year US Vice-President Mike Pence said if NASA failed to make a return visit within five years, “we need to change the organisation, not the mission”.

NASA has long sought to return to the moon in preparation for venturing farther to Mars but has suffered a lack of funds and organisational dysfunction.

Budget cuts have left NASA lacking even a suitable moon lander, says Jim Bridenstine, a former Republican senator who became NASA administrator.

China harbours moon ambitions but has pursued a different path: orbital missions and lunar rovers. In 2014 it landed an unmanned capsule on the far side of the moon, a first. Its Chang’e 5 mission plans to land a craft on the lunar surface this year to scoop up samples. It also wants to build a lunar research station.

Russia has a less ambitious target of landing cosmonauts on the moon by 2030.

India already has contributed to our knowledge of the moon. In 2008 the orbiter Chandrayaan-1 helped confirm the presence of lunar water. A follow-up mission scheduled last week was delayed because of technical difficulties. It includes a lunar lander and rover.

In April SpaceX — the private US aerospace manufacturer and space transportation services company founded by Elon Musk — used its Falcon 9 rockets to help a privately funded Israeli probe on its way to the moon, but the craft crashed into the surface.

Japan has ambitions for the moon and Mars.

Australia could be a contributor to such missions. CSIRO astronomy and space science deputy director Sarah Pearce says our expertise in mining and remote operations will be invaluable in space industries.

“We have a very strong mining, robotics and autonomous operations sector, and I think that’s an area that we and certainly the (Australian) Space Agency have identified as potentially an area where Australia can contribute to these large international missions,” she says.

But will the public back space exploration by humans if it comes with a price tag of billions of dollars? In an Associated Press/University of Chicago poll conducted in May, 68 per cent of respondents in the US wanted the space program to concentrate on monitoring asteroids and comets that could impact Earth. Only 27 per cent wanted the US to send astronauts to Mars, and less than a quarter (24 per cent) prioritised returning astronauts to the moon.

Putting humans in new worlds may be great entertainment and inspirational, but will we put our money where are mouths are?

There is, however, a great scientific narrative for humans visiting and colonising Mars — humans will need to learn to break their bonds with Earth to visit Mars. We will need to survive without a lifeline to Mother Earth and become independent, interplanetary travellers.

At one stage of its two-year orbit, Mars is on the opposite side of the sun to Earth. While its closest approach to Earth is about 54.6 million kilometres, it can be up to 401 million kilometres away. That’s more than 1000 times the distance from Earth to the moon.

A radio signal will take up to 20 minutes to travel in each direction. The opportunity to go or send supplies to Mars will come once every two years. Astronauts on Mars will be totally self-sufficient, making their own fuel, replenishing their oxygen supplies and growing food. They’ll probably use 3D printers to create housing and buildings.

Jason Crusan, director of advanced space exploration systems at NASA, in an earlier interview with The Australian, said astronauts on Mars can’t afford to rely on Mission Control to solve every issue. “The whole analogy of ‘Houston, we have a problem’ and they come back and say ‘Yes what is it?’ some 40 minutes later is not something you can operate with Mars.”

Nor is it feasible or affordable to continually send rocket after rocket with refreshed oxygen supplies, water, rocket fuel, medicines and building materials. Like a conquering Napoleon, astronauts dependent on Earth would face the hardship of overextended supply lines. Instead of having a lifeline to Earth, astronauts on Mars need a new skill set if they are to stay for any length. But mankind will gain the skills to travel even deeper into space.

New techniques are on the horizon to help. Scientists say it is possible to use electrolysis to split water into its constituent atoms and produce hydrogen for rocket fuel and oxygen for life support. For any of this, astronauts will need a water supply and a way to access it. This isn’t going to happen easily, with some water being detected on the moon and Mars but mainly at their poles, in challenging, inhospitable environments. Some hope we’ll find water on the Martian moons, Deimos and Phobos.

Astronauts also will need psychological conditioning to spend years in an isolated, hostile Martian environment where radiation, lower air pressure, toxic dust, the carbon dioxide atmosphere and freezing temperatures can each kill in a flash.

This is where our moon comes in as a vital training ground before living on the red planet. NASA says it is working with US companies and international partners to establish a permanent presence on the moon. It says that apart from being a training ground for astronauts, a lunar colony will make new scientific discoveries and lay the foundation for private companies to build a lunar economy.

A spaceship called The Gateway will orbit the moon and support human and robotic missions to the surface. NASA says The Gateway also will support months-long crew expeditions to the lunar surface. The moon also will be a great location to launch spacecraft, which will need only a fraction of the fuel required for an Earth launch. NASA says it will start testing its space launch system for sending humans into deep space next year.

The moon and Mars loom large as exploration targets for mankind and for scientific research, with the moon a testing ground for Mars endeavours. Private sector investment and participation are key to the success of a new moon venture, which will open up a new frontier for industry and international partnerships.

Our space ventures need to be thoroughly executed. More than 50 years ago, when the US decided to land a human on the moon, there was a proposal that fortunately didn’t see the light of day. It involved sending a US astronaut on a one-way trip to the moon with a promise that he eventually would be brought home when the necessary technology made a return possible. Subsequent rockets would supply food, water and oxygen for the stay. This way, an American could be on the moon by 1965.

While it’s hard to confirm, the Soviet Union may have thought about a similar mission. There is an online reference to it. “The saddest story connected with the moon is a written statement from a part of the Soviet cosmonauts — a cosmonaut detachment to the top management about their readiness to fly only in one direction (kamikaze) for the sake of primacy,” says one commentator in Russian, translated here to English. “Fortunately it was decided for the political effect to be dubious.”

Hopefully similar shortcuts won’t be contemplated as we venture to Mars. It will take decades to do the job properly. But will the public support these endeavours once the glow of enthusiasm over the 50th anniversary celebrations of Apollo 11 dies down?