Neglect fuels our Pacific family feud

Many comment with alarm that a Chinese military base might be established in Solomon Islands. But it’s also worrying to discover how little we know about that country, given it’s so close.

While all happy families are alike, Leo Tolstoy wrote, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

Australian politicians these days seek to signal their virtue as friends to our island neighbours by describing them as our “Pacific family”. But disappointingly few Australians have much of a clue about our new-found Pacific kin, including how they are almost as diverse as the countries of Europe.

Thus one of the more unusual, though also welcome, features of this election campaign has been that not only foreign affairs but also Pacific Island affairs have emerged as high-profile issues.

Many have commented with alarm that a putative Chinese military base might be established in Solomon Islands, so close to Australia. That is alarming. But it’s also a little worrying to discover how little we know about that country, given it’s so close.

Keeping China out is not best achieved by muscular public rhetoric about “keeping China out”. In the Pacific, as everywhere, people prefer to be valued for themselves.

University of Papua New Guinea academic Patrick Kaiku has warned that condescending rhetoric “will push Pacific political elites towards China”, while building long-term partnerships would instead develop “a powerful ally when the corrosive effects of China’s debt-trap diplomacy or militaristic agendas need confronting”.

Since its “discovery” by Europeans in the 18th century, the Pacific has suffered being viewed as a paradise. One big happy family? But no. Never truly a paradise. Just people trying their best to survive and thrive in often challenging environments.

Then a suite of European powers, as well as the US and Japan, established colonies there, investing little in what were mostly afterthoughts, reluctantly acquired following merchant lobbying. Many gained independence in the 1970s in a wave following African decolonisation, and thereafter attracted scant attention – including in 1978 the British Solomon Islands Protectorate.

Their tyranny of isolation, with small populations scattered across a great ocean that provided their core source of wellbeing, with inadequate infrastructure or educational inputs, swiftly led them to rely on aid to meet raised living standard expectations. It remains the most aid-dependent region of the world, per person – while political elites seek an easy ride by insisting the Pacific can have it all, unchanged traditional life alongside modernity.

Last year even the Pacific Islands Forum, the paramount regional organisation, suffered a grievous family breakdown, with the five Micronesian states walking out. The region’s main economic grouping, the Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations Plus, just 17 months old, contains only nine of the 14 island nations, with PNG and Fiji among those refusing to join.

About the time of PNG’s independence in 1975, some of Australia’s brightest emerging talents – people such as Ross Garnaut and Rod Sims – worked there for years. But interest in our former colony waned and today only a fraction of Australians have visited our closest neighbour, with its diverse, vibrant population of almost 10 million and its breathtaking landscapes. Ambitious Australians largely surmised that a focus on PNG or the broader Pacific would lead nowhere for their careers.

Living standards have improved, but painfully slowly. In the UN’s most recent Human Development Index of 189 nations, the only Pacific countries in the top half are Palau and Fiji – just – while PNG and Solomon Islands are in the bottom 20 per cent.

Island politicians became adept at courting international interest. Jon Fraenkel of New Zealand’s Victoria University has said many Pacific states “did rather well by playing on the rivalries of the Cold War era. They are in a good position to do so again” as a new cold war intensifies, this time between China and the West, and as new island nations emerge, in the medium term likely to include Bougainville and New Caledonia. Sadly, this amounts to marketing their own sovereignty, for those who have little else left to sell.

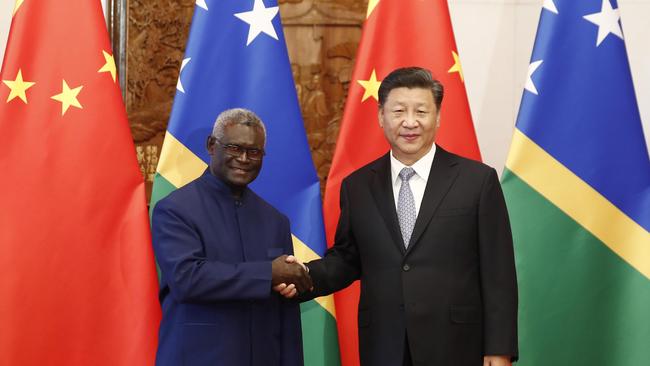

Australians may have gained the impression that China’s Pacific interest is new. But for decades it skirmished with Taiwan for diplomatic loyalty there. A dozen years ago Taiwan’s president at the time, Ma Ying-jeou, broke with this money-diplomacy bribery. China’s President Xi Jinping, however, pressed on to shrink Taiwan’s international space, in 2019 securing the switch of Kiribati and Solomon Islands, leaving the PRC with 10 island allies and Taiwan four. Veteran Pacific analyst Ron Crocombe published his book Asia in the Pacific Islands: Replacing the West 15 years ago as the shift of the world’s economic gravity towards East Asia, especially China, began to shake up old assumptions and alignments. Since the 1990s, Crocombe said, “conditions in the islands have attracted speculative ‘frontier’ enterprises from Asia seeking short-term gains using opportunistic techniques” – meaning corruption, especially notorious in logging.

The move towards China has been supercharged since Xi launched his “New Era”, weaponising the country’s economic heft and asserting the inevitability of “the West declining and the East rising” as he seeks to seize “the dominant position” in world affairs. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was transformed by the Xi ascendancy as he personalised and centralised power. Hence its wolf-warrior evangelisation and its rapid creation of a Pacific-focused diplomatic corps.

Yu Lei, of the Centre for Pacific Islands Studies at China’s Liaocheng University, has written that the extension of the Belt and Road Initiative to all Beijing’s Pacific diplomatic partners “reveals China’s desire not only to intensify its economic co-operation … but also to create a sphere of influence in the traditional backyards of the US and its major ally, Australia”.

He said Xi attached much more strategic significance than his predecessors to China-Pacific relations: “Politically, China hopes to acquire the (island nations’) diplomatic backing”, including in the UN and the Pacific Islands Forum, and “geopolitically, China wishes to attack the US and its allies in the Pacific to ensure its (global) rise”.

China dispatched to the Pacific, Yu wrote, “many more warships than ever before for information collection, reciprocal visits and military training, which provide the Chinese navy opportunities to improve its capability of deploying forces overseas far away from China” and gaining “capability of military revenge on any intervention into its territorial disputes or containment of its rise”.

Each major city in China’s industrial powerhouse Guangdong province has been assigned a Pacific country to boost its BRI connectivity, while many Chinese migrants have been arriving in the islands, especially from Fujian province. And state-owned corporations have likely suffered big losses on Pacific projects they have taken on – largely using Chinese labour – to achieve Xi’s strategic targets.

Members of Pacific elites have received frequent red-carpet visits to China but have largely failed to parlay this into useful, independently derived capacity to analyse its goals or how it works.

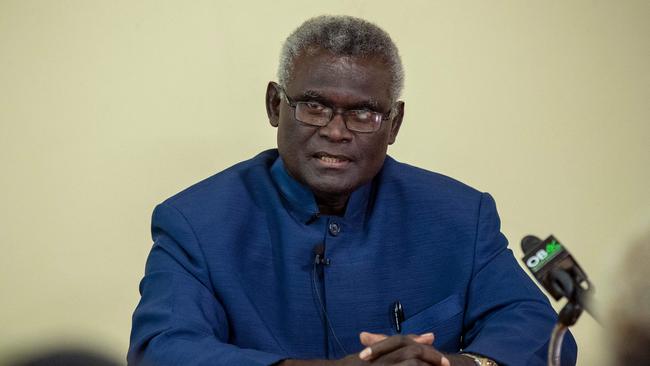

Thus Solomons Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare has said repeatedly that abandoning the progressive democracy of Taiwan for the People’s Republic of China placed his country “on the right side of history” – a favourite Xi phrase.

That sense of the inevitability of China’s success, that it represents the future and the West the past, is a powerful element in its regional influence. Pacific elites have failed to register that Beijing now finds itself skewered by triple-trouble largely of its own making – its unyielding zero-Covid lockdowns, its economic policy missteps slowing growth to a crawl, and Xi’s continuing loyalty to his “best, most intimate friend” Vladimir Putin.

The Solomons’ foreign affairs motto is “friend to all, enemy to none”. Yet – adopting a key phrase of Nazi philosopher Carl Schmitt whose influence is now widespread in Chinese universities – Beijing seeks to distinguish clearly friends from enemies.

As in Australia, popular Solomons sentiment differs from elite inclinations towards China. A survey of 1526 adults in its nine provinces six months ago found that 91 per cent preferred diplomatic alignment with liberal democratic countries, just 9 per cent with China, while 79 per cent said the Solomons should not receive financial aid from China and 83 per cent said there was corruption in their national government, which 68 per cent said was increasing.

The single-chamber, four-year Solomons parliament comprises 50 members, of whom 21 are independents and the rest belong to eight parties. Such fragmentation means the chief goal for an ambitious and cunning politician – and there is none in the Solomons more ambitious or cunning than Sogavare – is to focus unremittingly on ensuring the backing of 25 MPs for their election as prime minister, then to retain that support against no-confidence votes.

The pandemic has made this easier for Sogavare, now in his fourth separated term as Prime Minister. He wields extra powers under the continuing state of emergency he introduced in March 2020, including control of who can enter the country, reduced parliamentary oversight and media constraints.

National development funds, ubiquitously called “slush funds”, distributed to individual politicians with scant if any accountability, have steadily grown in both PNG and the Solomons into major elements of government budgets.

Earlier, Taiwan contributed towards such dubious funding in the Solomons. Taiwan’s president Ma frankly conceded during a visit: “We’ve been accused of doing things not quite acceptable by international standards.” China now chiefly funds this program in the Solomons, with each MP who backs Sogavare receiving $44,000.

The Solomons’ most populous island, Malaita, with a third of the 650,000 total population, strongly opposed Sogavare’s 2019 switch from Taiwan to China. Malaitans were prominent among rioters in Honiara protesting against Sogavare’s rule late last year who were quelled by Australian, Fijian and PNG security forces. Australia previously had spent $2.6bn in backing the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands that stabilised the country from 2003 to 2017 after violent turmoil.

Sogavare represents a uniquely Solomons style of leadership, in the mould of his original mentor Solomon Mamaloni, also previously a top public servant and prime minister four times, who died in 2000: enigmatic, aloof, exuding a sense of the hidden capabilities of a traditional big man, impressing his peers with strongly contrarian – and, as we have seen this week, sometimes ridiculous – rhetoric that evinces pride in independence from powers such as Australia.

The Solomons’ main challenges, according to another poll, are unemployment, cost of living and corruption, issues that attract only limited attention from the political leadership. No wonder the polling also says the most trusted leaders are church heads.

The Solomons struggles to attract investment; serial projects having failed. And Chinese firms substantially use their own labour for new infrastructure they are building for the 2023 Pacific Games, including an international airport. But Sogavare can survive until next year’s election by keeping the support of his couple of dozen MPs.

Will China build a military base there? Sogavare emphatically denies it, adding: “Australia remains our partner of choice and we will not do anything to undermine Australia’s national security.”

Beijing – whose sole overseas base is in Djibouti in East Africa – in recent times has boasted of its capacity to rescue Chinese people in danger anywhere. The 2017 blockbuster film Wolf Warrior 2 that gave its name to China’s new diplomatic style features a heroic evacuation from Africa. Forward-locating forces ready to rescue or defend hapless Chinese from future Solomons or other Pacific rioters would be a bold but not fully surprising goal for the new Beijing-Honiara security deal.

Besides the world’s most beautiful lagoon, Marovo, the Solomons also contains the glorious harbour – and potential naval base – named by Spanish explorer Alvaro de Mendana in 1567, “Thousand Ship Bay … where the whole Spanish Armada can anchor”. But while China may press for a permanent base, Sogavare is well capable of prevaricating, adding new and burdensome requests, exhibiting his passive-aggressive contrarianism to frustrate Beijing, even while he may also continue to irritate Canberra, whoever is in power.

Our answer to such challenges has been the Pacific Step-Up, including a “whole-of-government framework” involving development, diplomatic and defence capabilities. But it isn’t working well enough. For instance, Australia’s big announcement at the 2018 Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation leaders’ summit in Port Moresby was a project to electrify 70 per cent of PNG homes by 2030, with just 15 per cent having access to power. The US, Japan and New Zealand were to join in this overdue and important work. It has achieved, however, almost nothing, a third into its timeline.

Australia needs a whole-of-Australia framework instead of whole-of-government, involving not only Canberra but also business – we have lively business councils connecting Australia with PNG, Fiji and the Pacific broadly – and churches, sports organisations, universities and state and city governments.

We have already lost too much of our former retail banking dominance but should retain what’s left, and back our other businesses that operate in the region, especially those facing unfair, loaded competition. The forces that kiboshed, for instance, the patient efforts of Ryan Mount’s Axiom to establish an environmentally sound nickel mine in the Solomons should be opposed more firmly.

Australia largely abandoned former scholarship programs bringing Pacific islanders, especially from PNG, to study here, instead funding education there. But we could do both. Our “soft aid” has contrasted with China’s highly visible infrastructure construction, albeit criticised for poor quality. Our aid should reflect genuine Pacific priorities.

As well as bringing in more Pacific students, we also can increase our visas for workers from the region – and not only in agriculture.

Our diplomatic service must catch up with China’s by incentivising a cohort dedicated to the Pacific. We should boost our military and police exchange programs, and encourage a range of institutions including schools, universities and hospitals to partner with Pacific counterparts.

As Australian Strategic Policy Institute senior analyst Anthony Bergin has suggested, we could bulk up volunteer schemes to place young Australians with professional skills in the Pacific for set terms.

No one says family life is always happy. Or easy. All families feud sometimes. But the Pacific is more than a family. That metaphor is useful but doesn’t say it all. China is not just a mean outsider insinuating its way into the family home, although it is also that. And Australia needs to become more than a kindly uncle wagging its finger about Beijing. Building stable liberal democracies that serve their Pacific populations’ core developmental needs is the main game that requires long-term bipartisan support from us.

Rowan Callick, an Industry Fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute, has worked for 10 years each in PNG and China.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout