Natural balancer to China: It’s time for Australia to cement ties with India

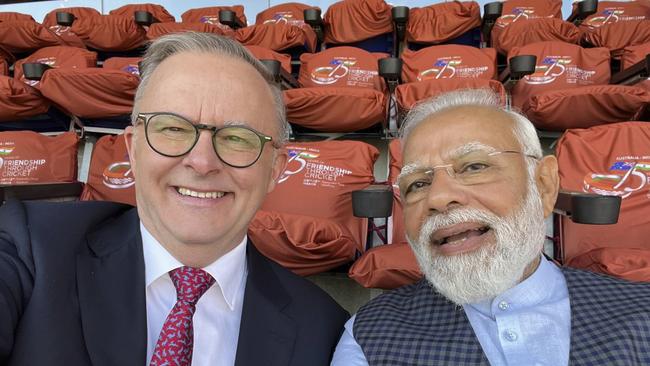

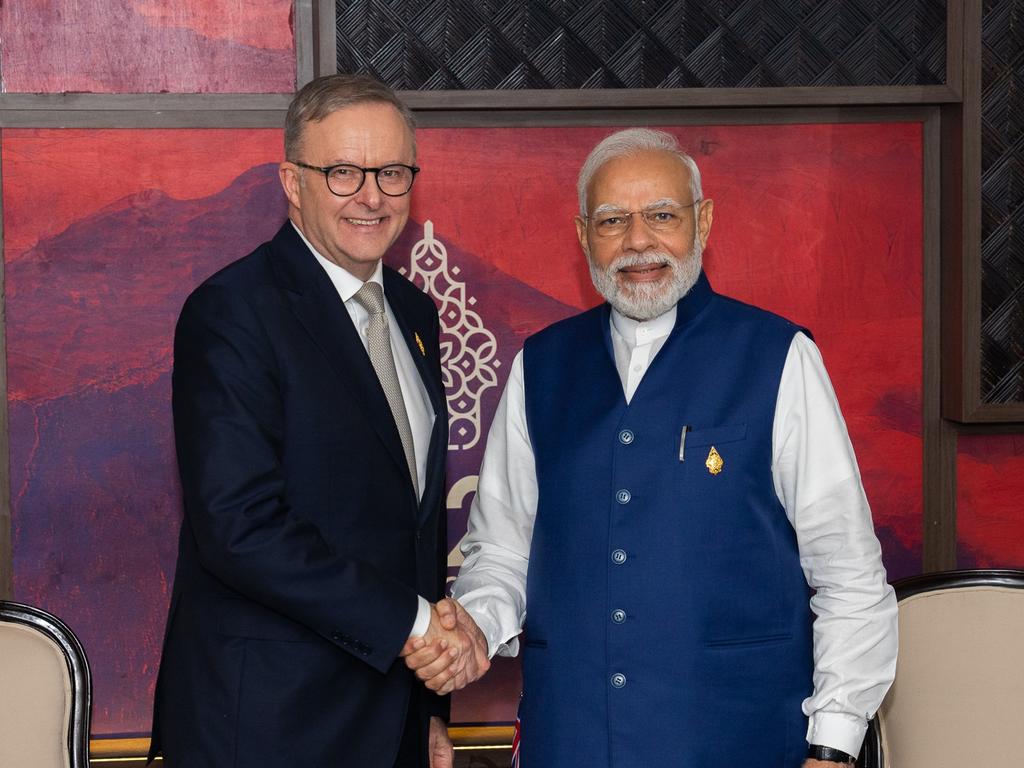

The longest courtship in our diplomatic history, the Australia-India relationship has always been underdone. Anthony Albanese rightly has big business with Modi and Biden this week.

In India, Albanese is giving flesh to a strategic partnership long in the forecasting but slow to take real shape. In the US he will announce a revolutionary deal to acquire nuclear-powered submarines in the shortest time possible.

The two key institutions, the Quad and AUKUS, didn’t exist 10 years ago. The background to the geo-strategic relationship with India and the decision to acquire nuclear-powered submarines is the need to respond to China’s growing military assertiveness.

But both the US and India embody positive, life-enhancing relationships for Australia, based on shared values as well as shared interests.

In San Diego, Albanese will announce that Australia will buy three to five US Virginia-class subs off the shelf, so to speak, co-design with the Brits and Americans a common AUKUS sub to be built in Adelaide, and by 2027 have US nuclear-powered subs rotating through Perth, as US marines rotate now through Darwin.

That still doesn’t equip us militarily for the next few years, but it’s the most rapid means by which we could possibly acquire game-changing nuclear submarine capability. With the Defence Strategic Review to be published early next month, this should be a huge step up in military capability, and in the intimacy of our alliance with the US and our long, deep partnership with the Brits.

Nothing quite so dramatic will happen with India, though there will certainly be plenty of colour and movement. New Delhi is increasingly fundamental to Australia. The Indian relationship is exciting, dynamic, full of possibility. India is a giant swing state of history. Already immensely influential, its global presence will only grow. It offers Australia the chance of a new dimension of national policy. The relationship with India, and indeed Albanese’s trip there, will embrace everything – trade, security, people to people relations on a unique scale, and the deepest cultural engagement.

Albanese is crowning a deep change in our relationship with India. Deakin University is the first foreign university to open a campus branch in India. This year, for the first time, Australia will host India’s Malabar naval exercises, involving India, the US, Japan and, now seemingly permanently, Australia. That’s the Quad on the high seas.

At 1.4 billion people, India is the most populous nation. Nearly a million Australians claim Indian heritage. Nearly 700,000 Australians were born in India. India is the fifth biggest economy, following the US, China, Japan and Germany. It’s likely to reach No.3. It’s our sixth biggest trade partner but fourth biggest export market. India will see economic growth of 6 to 8 per cent in the next several years, a fantastic rate given the state of global finances. It will be the fastest growing big economy.

India is Asia’s natural balancer to China. It doesn’t need to become anyone’s formal ally or join any military bloc. Just by asserting its own strategic personality it provides the natural Asian balance to Beijing.

But the Australia-India relationship has always been underdone. It’s the longest courtship in our diplomatic history, sometimes ardent, sometimes quarrelsome, frequently indifferent, never quite consummated. No one understands this relationship more deeply than former Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade head Peter Varghese, who served as high commissioner to New Delhi.

In 2018 he produced a report for government, An Economic Strategy to 2035. It was weirdly neglected by the Coalition government, which didn’t launch it so much as allow it to escape in a moment of inattention. Albanese, on the other hand, repeatedly cites the Varghese report.

Varghese argued the scale of India’s economic growth was so great Australia couldn’t afford to ignore it. He cited deep structural complementarity between the Indian and Australian economies. So many things that India needs, from coal and rare earth minerals to education and financial services, Australia provides. Varghese argued India should move from our sixth largest trade partner to our third by 2035.

He thought there was greater potential for two-way investment than with most other Asian economies. Although India is a challenging business environment, it’s a high-growth economy, has a relatively open investment regime, its institutions are familiar to us, it has the rule of law and English is widely spoken.

Varghese saw a growing convergence in geo-strategic outlook between New Delhi and Canberra. This arises partly, but not entirely, from concern about China.

But India’s strategic orientation has changed beyond just China. New Delhi values its strategic autonomy and won’t join a military bloc or formal alliance. During the Cold War, though a democracy, it was close to the Soviet Union, not least because Washington tilted to Pakistan. India needed what friends it could find. After the Cold War, New Delhi reached historic new understandings with the US and its allies such as Australia. Under John Howard, Canberra reversed its irrational ban on exporting uranium to India. Labor foolishly restored the uranium ban for some years but it too finally acknowledged reality and opened up uranium exports to India.

Varghese’s report argued that India offered the deepest possible people to people links. This has already come true in our magnificent Indian diaspora community. Australians of Indian extraction are proudly Australian but they naturally furnish a bridge between the two countries. Australians of Indian background are highly successful in education and employment. Varghese forecasts that Indian Australians will become the most politically active and influential ethnic community since the Irish.

Indian culture is already a species of global soft power. Throughout Southeast Asia, and across the Middle East and in the UK, Indian movies are clearly second only to Hollywood in range and reach. So much Indian culture happens in English. Indian novelists have won every prize literature offers.

Historically, Indians are seen as the victims of colonisation but also as history’s winners. As much as any nation, India has taken constructive measure of its colonised past. Instead of being consumed with resentment, India has conscripted colonial buildings, colonial history and above all its own distinctive and superlative mastery of the English language, to serve as formidable assets of the contemporary Indian personality.

Of course, India is also a land of sorrows. It’s a vast nation of 1.4 billion, many of whom are still poor. In any nation of that size terrible things happen every day; wonderful things also happen every day.

Narendra Modi, of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, has been a successful prime minister. Although India has by no means a perfect record of economic reform, Modi, since winning office in 2014, has enacted profound economic change. He passionately wants development. He introduced a national GST, which more than anything unified the national economy. He reformed bankruptcy laws. He increased infrastructure investment. India desperately needs more roads and rail connections, more ports and more buildings. Modi, though a strong nationalist with protectionist tendencies, has attempted to clear space for the private sector. The Indian economy to some extent is dominated by giant conglomerates such as the Adani Group, Tata and Reliance.

It bears some resemblance to South Korea when it was dominated by giant chaebol. Throughout that era, I read many books on how dysfunctional and sub-optimal such chaebol dominance was. Yet every book started on page one with South Korea wretchedly poor and undeveloped after the Korean War, and finished on the last page with South Korea an industrial powerhouse and middle-income economy. India’s economic model is different from East Asia, but no Asian growth story beyond a couple of entrepot city-states has really followed any kind of textbook path.

In an important speech at the University of Queensland last year, Varghese updated the outlook of his report. He identified structural factors producing momentum for Indian economic growth. These include: urbanisation of the biggest rural population in the world; transformation of the informal economy, still the bulk of Indian economic life, into a formal economy; a young population with an average age of 28; massive infrastructure investment; massive education investment. To which might be added the dynamism of India’s global diaspora and the almost panting desire of almost the entire world to have an economic growth story that isn’t China.

So many things about India’s economic development have been unique. The way it leapt straight from subsistence to hi-tech mastery, with dazzling firms such as Infosys, has had huge benefits for the poor. Rajiv Gandhi, prime minister in the 1980s, remarked that only 15 per cent of welfare spending got to the poor.

India has used its hi-tech, online genius to create unique identification numbers, secured by biometric data, which has brought hundreds of millions of people into the banking system, enabling welfare payments to go straight to their bank accounts.

Of course, there has been a difficult side to the Modi years. Modi emerges from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh movement. The RSS is a Hindu nationalist movement that promotes Hindutva.

A thousand books could be written about Hindutva and the RSS. It’s essentially a desire to assert Indian cultural identity. It can be benign or nasty. It doesn’t need to be against any other religion. But there’s no doubt that some of its followers are hostile to non-Hindu religious identities.

Generally the RSS is not against democracy, it doesn’t seek the overthrow of democracy but it doesn’t believe in Western-style liberalism. Modi doesn’t encourage or sanction intercommunal violence. But he has motivated his voters in part on the basis of nationalism and at times on the basis of their Hindu identity. Because India is a majority Hindu nation (about 80 per cent of Indians are Hindus) he can win government by winning an overwhelming majority of Hindu support.

Nonetheless, his power shouldn’t be overstated. Indian state governments are powerful and more than a dozen states are controlled by parties hostile to the BJP. There is certainly a cult of personality around Modi but that was also true of several of the Gandhis in the decades when the Congress Party dominated India as thoroughly as the BJP does now.

Indeed the BJP, though more a national party than any other in India, is still mainly restricted to the Hindi belt in the north. Regional parties dominate numerous states. Affect, grandeur, dynasty, personal charisma, mysticism, patronage, every element of celebrity – these have been the stuff of Indian politics for decades. Each nation has its own style.

Plenty of voices in the Indian media are hostile to the government, which could easily lose next year’s election. Indian elections are unpredictable.

Some state governments influenced by the RSS have passed extremely obnoxious laws regulating or restricting religious conversions. This is a blatant interference in religious freedom. India is nonetheless still more free in religious practice than almost any majority Muslim nation, for example. But there have been really, really nasty communal incidents. You can certainly argue Modi should have stood more strongly against this. You cannot, however, seriously argue that Modi is a fascist or that India is no longer a democracy.

Varghese offered a typically measured assessment in his Queensland University speech: “There have been several periods in India’s 75 post-independence years when its liberal democratic character has been sorely tested, most notably the period of the Emergency under Indira Gandhi. Today there are again signs that the liberal democratic character of India is under pressure.

“I do not share the view that India has already become an illiberal democracy. But there are indeed signs that minorities fear for their freedoms, that incitements to communal violence are met with silence, that charges of sedition are misused to advance a communal agenda and that key institutions tasked with independence may be too accommodating of the wishes of government … But when it comes to democracy in India I tend to the view which is often ascribed to the US, namely, there is nothing wrong with Indian democracy which cannot be fixed by what is right with Indian democracy. True democracies are ultimately self-correcting and I have long had the view that India is a true democracy.”

India and the US are, like us, true democracies, flawed and glorious, like us. They are also our close friends. Albanese rightly has big national business with both.

Anthony Albanese is taking care of business in the most urgent possible manner as he travels through India and on to San Diego. India and the US, the world’s biggest two democracies, two key partners in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue.