Native title gets a fresh lease of life, if only Dr Yunupingu had lived to see it

This week’s High Court decision in the case brought by Dr Yunupingu is a victory for traditional owners’ rights. While the issue may now be clear in law, the ramifications will be complex.’

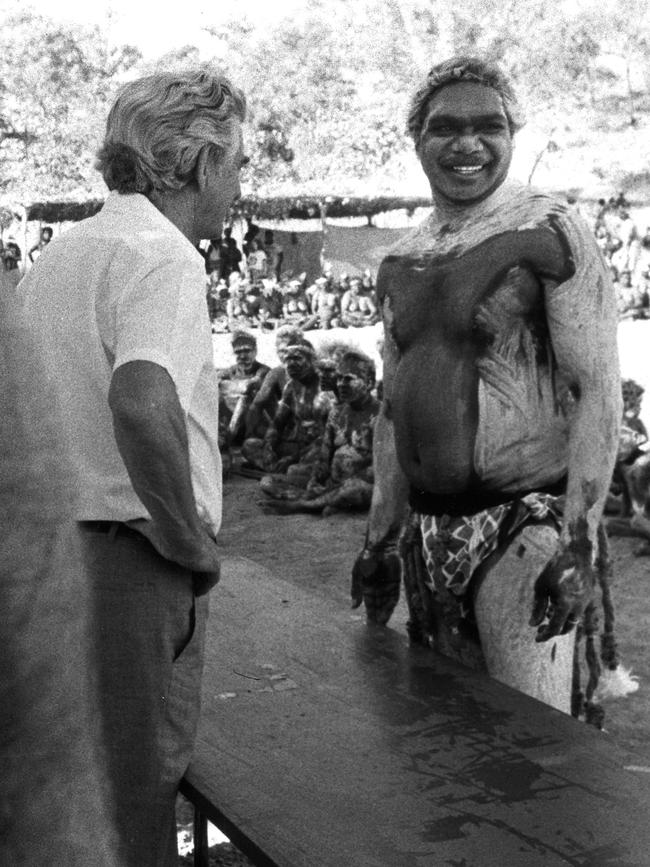

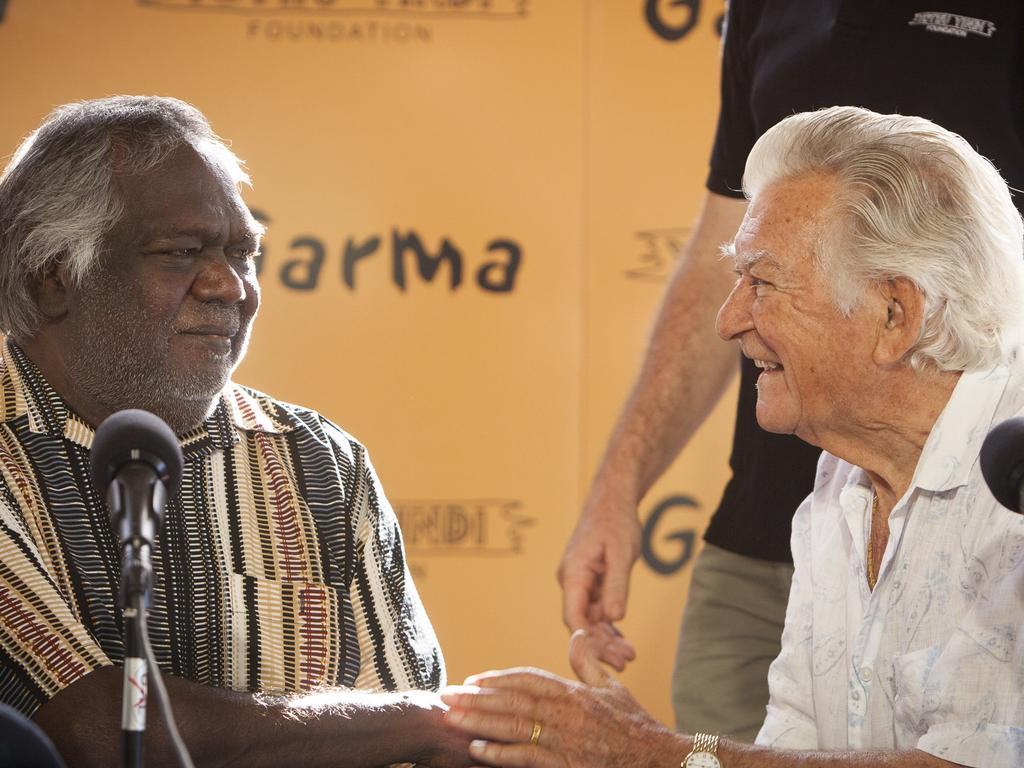

Dr Galarrwuy Yunupingu (1948-2023) of the Gumatj clan was determined to ensure that the ancient patrimony of his people was recognised and treated equally under Australian laws. In 2008, he wrote, “Our allegiance is to each other, to our land and to the ceremonies that define us. It is through the ceremonies that our lives are created. These ceremonies record and pass on the laws that give us ownership of the land and of the seas, and the rules by which we live.” His great desire was to secure the survival of his people into the future. His greatest fear was that they and their traditions would be obliterated by the occupation of their world by missionaries, mining company and government personnel and encapsulation by an uncaring nation.

If only he had lived to see the decision of the High Court of Australia on March 12, confirming that this ancient Yolngu property governed by their laws should be treated equally with all other property under our Constitution and acquired by the commonwealth only on just terms.

His brothers Djawa and Balupalu were present at the High Court in Canberra to hear the judgment and their sense of vindication was palpable in Djawa’s reported response: “Justice has been served in this country for my people and the people of northeast Arnhem Land. It’s for the future of my people, and our children, and their children.” Sean Bowden, the lawyer representing the Gumatj clan, observed that the case confirms the “rule of law in this country”. While further litigation must follow in relation to any eventual compensation amount, the Gumatj people are one large step closer to securing their survival in a much harsher world than the one Dr Yunupingu experienced during his life and in which he dreamt of a better future.

The decision confirms that the commonwealth invalidly acquired their rights in a long history of unjust dispossession. Section 122 of the Constitution does not give the commonwealth power to acquire property other than on just terms. Ergo, the Gumatj clan is entitled to compensation by the commonwealth in respect of grants of interests that had the effect of diminishing the Gumatj clan’s pre-existing property rights. Further, the court considered whether a pastoral lease granted in 1903 by the governor of South Australia “had the effect of extinguishing any non-exclusive native title rights over minerals on or under the subject land. The answer is it did not.”

Acts of dispossession followed. In 1938, a “mission lease” was granted to the Methodist Missionary Society. In 1939, the crown purported to acquire total rights to all minerals in the Northern Territory as the “property of the crown”. This purported acquisition was reiterated in the Minerals (Acquisition) Ordinance 1953 (NT).

The words of section three of this ordinance include: “(A)ll minerals existing in their natural condition … on or below the surface of any land in the Territory, not being minerals, which, immediately before the commencement of this ordinance, were the property of the crown or of the commonwealth, are, by force of this ordinance, acquired by, and vested absolutely in, the crown”.

From 1958 to 1969, five special mineral leases were granted by the commonwealth over parts of the claim area. The Gumatj clan contended that each one of these acquisitions was constitutionally invalid and refuted that they could extinguish their non-exclusive native title rights.

The Yunupingu case, as it will be referred to, delivers long-awaited justice to the Gumatj clan. This case responds to an appeal by the commonwealth to reject the Federal Court’s findings in this matter. The High Court dismissed each of the commonwealth claims and clarified the notion of common law recognition of native title. The legal fraternity and native title practitioners will read these arguments with interest.

The case will return to the Federal Court to decide on several remaining legal matters including the exact amount of compensation owed by the commonwealth to the Gumatj clan.

The court found that native title is “property”, property that is “enduring, substantial and significant”, and “protected by s 51(xxxi)”, the clause of the Constitution providing for commonwealth acquisition of property only on just terms from any state or person for any purpose.

This part of the decision corrects the confusion caused by those who sought to diminish the common law recognition of native title by relegating it to a “bundle of rights” and “inherently fragile” title in a flawed attempt to deny native title the status of a type of property attracting the protection of the constitutional right to just terms compensation for compulsory acquisition.

The reasoning of the court on this matter is an elegant reminder of the “central basis for recognition of native title in Mabo (No 2)”. Justice Gerard Brennan overruled all earlier cases on terra nullius in that landmark case, stating, “(T)o maintain the authority of those cases would destroy the equality of all Australian citizens before the law. The common law of this country would perpetuate injustice if it were to continue to embrace the enlarged notion of terra nullius and to persist in characterising the Indigenous inhabitants of the Australian colonies as people too low in the scale of social organisation to be acknowledged as possessing rights and interests in land.”

In the Yunupingu case, the judges relied on several arguments about the import of common law recognition of native title, and particularly the rejection of terra nullius. They refused to perpetuate this “injustice based on an historical fiction”. The judges rejected the commonwealth argument that the “inherent fragility” of native title and its susceptibility to extinguishment and preserved the “rationale of equality before the law” because to do so would “destroy that equality and perpetuate its own form of injustice”.

The question of whether common law recognition of native title extends to minerals has finally been clarified at law. This matter will exercise the minds of lawyers advising the commonwealth and, eventually, the members of the cabinet. The issue may be clear in law, but the ramifications will be complex. The standard retreat of Australian governments to brazen racial discrimination to deny this development in common law rights may not be straightforward.

Already, hysteria is building about the ramifications of this case because of poor reporting of a densely drafted judgment. The usual suspects are beating their drums about “taxpayers” supporting Aboriginal claims, but they are driven by the usual feverish electoral campaign confections to excite voters well primed for denying equality to Indigenous Australians by the hateful No campaign against the referendum question on recognising us in the Constitution. How much compensation the commonwealth should pay to the Gumatj clan is yet to be determined before another court. There is no doubt, though, that this historic judgment will provide much grist for the mill of the politicians who habitually incite fear about Aboriginal people as wastrels “getting too much”. Opposition legal affairs spokeswoman Michaelia Cash has jumped the shark with this predictable demand: “This money should be used to improve the situation for people on the ground. We need full transparency on how these funds will be spent to ensure that is the case.” Aboriginal people were, at law, “wards of the state” for many decades. This attitude continues today in the approach to state interference in our daily lives and our organisations – as evidenced by Cash’s view. The point of the Gumatj case is that any compensation paid is the private property of the Gumatj clan.

The case will be directly relevant only in the NT, which was administered by the commonwealth for more than 60 years, or, perhaps, in another commonwealth territory and only under specific conditions. Perhaps by 2026 or later, when the Federal Court settles remaining legal issues and how much compensation is owed and for what, the hysteria may subside. We can expect a crescendo of drum beats in May this year, and if Cash is installed as Attorney-General, a great deal of entertainment as the legalities of prying into the private lives of Aboriginal people form the plot of the next season of the national soap opera of racialised politics.

Some observers of the case have mentioned the movie The Castle (1997), an Australian comedy about the Kerrigan family fighting to save their home in the suburbs from demolition for an airport expansion, with the famous line, “It’s the vibe of the thing, your honour”. The dispossession and legal arguments of the loveable, white Kerrigan family could, we once hoped, inspire a commitment from Australians to the principle of equality before the law. We hope that we do not find that our political and legal rights as Indigenous people to this principle of equality are inherently fragile.

The legacy of Dr Yunupingu will be the High Court’s clarification of the constitutional issues that Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus wanted on behalf of the commonwealth. Dreyfus: “The commonwealth appealed to the High Court to settle critical constitutional issues in this case. This decision clarifies the Constitution’s application to those issues for parties to this and future matters.” It should come as no surprise to him, then, that the High Court confirmed the equality of native title as a “species of property” and the equality of all citizens, including those in the territories, to just terms compensation for compulsory acquisition of their property. It should not be a surprise that common law recognition of native title can extend to minerals on or below the ground. How many times have we heard “from the tops of the trees to the roots of the earth below”? The content of native title rights and interests must now be conceived of in the way that the Brennan court did in Mabo No 2.

The recognition of native title was fundamentally misunderstood by the lawyers for one of the commonwealth parties who resorted to applying eugenicist terms such as “congenital infirmity” to the notion of native title.

The High Court summarised its rejection of several flawed arguments: “The preferable view is that the common law rule of recognition was and remains absolute.”

Marcia Langton is a Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor at the University of Melbourne. Jamie Lowe is chief executive of the National Native Title Council.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout