Nation is banking on Josh Frydenberg to deliver post-Covid prosperity

With the RBA on the sidelines, the Treasurer’s policy credentials face their biggest test.

Big numbers bend and bounce around but they cannot be denied: $251bn of direct economic support committed by the Morrison government. Revealing the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook on Thursday, the federal custodian told reporters more than $138bn had already gone out the door to households and businesses.

In the current financial year Canberra has asserted itself as the Big Australian, with $671bn of spending on new job programs and more bureaucrats, and bets on vaccines and all the other things the federal government does year in, year out. That’s equivalent to 35c in every dollar spent or earned in this country.

Who would have thought the man who in his first budget in April last year extolled thrift and self-reliance, and other values his side of politics claims in its branding, would be shovelling dollars out of Treasury with such alacrity?

But this is the task in a long season of economic woe and with no fiscal constraint in a money world of (almost) free and easy, Frydenberg has done what his officials have guided him to do: jobs first, debt reduction in the beautiful tomorrows.

The scoreboard at the end of a distorted year in politics and economics favours the brave, but the play keeps moving into new phases, especially with the virus at large.

Does the Treasurer have more ideas in the tank? Frydenberg has no choice because the short-run policy game has changed and he is in charge in a way even his Liberal predecessor Peter Costello could not have contemplated.

With the Reserve Bank effectively on the sidelines for a self-imposed time-out for “three years”, Canberra has to do the heavy lifting. As veteran budget watcher Chris Richardson noted this week, “something important changed during COVID, and Australia needs to understand it”.

“Until now, budgets could concentrate on longer-term issues, and leave the Reserve Bank to handle the ups and downs of the economy by raising or lowering interest rates,” the partner at Deloitte Access Economics wrote ahead of MYEFO.

“But not any more — the RBA already has its foot to the floor. For the foreseeable future, that says budget policy has to be more agile than it’s been in times past. That means a greater willingness to use the budget to help juggle the ordinary ups and downs of the economy. But any moves of that type (such as tax surcharges and discounts and spending shifts) will necessarily need to be temporary, which will also require an understanding of that from both the public and from the opposition of the day.”

Ten weeks ago, on budget day, a homesick Frydenberg was already changing gears from emergency cash to tax cuts for households and incentives to business to invest and hire, particularly young unemployed people.

The two biggest programs the federation has seen in JobKeeper and boosting cashflow for employers played their roles in the June and September quarters, keeping workers attached to their employers and money flowing into the economy. The wage-subsidy lifeline, powering down next month to a maximum $1000 a fortnight, is expected to cost $90bn by the end of March.

At one point, 3.6 million people were receiving the then $1500 payment. Since September the number of people receiving JobKeeper has fallen by two million.

“We have come a long way from Treasury’s initial estimate early on in the pandemic that the unemployment rate could hit 10 per cent by year end or 15 per cent in the absence of JobKeeper,” Frydenberg said, adding RBA research showed the wage subsidy saved at least 700,000 jobs.

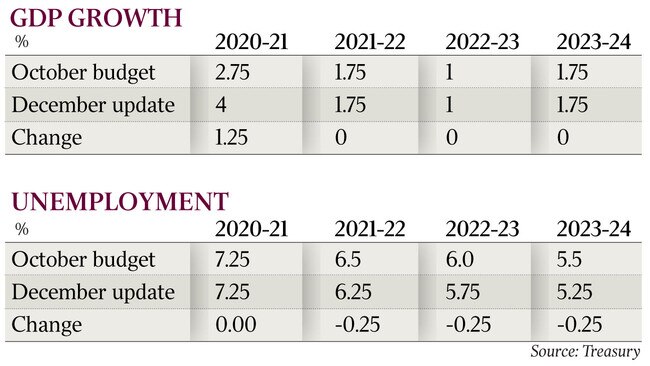

In a MYEFO statement with Finance Minister Simon Birmingham, the Treasurer said around 85 per cent of the 1.3 million people who lost their job or were stood down on zero hours in April are now back at work. Treasury is forecasting gross domestic product growth of 4.5 per cent next calendar year, following an expected 2.5 per cent fall this year.

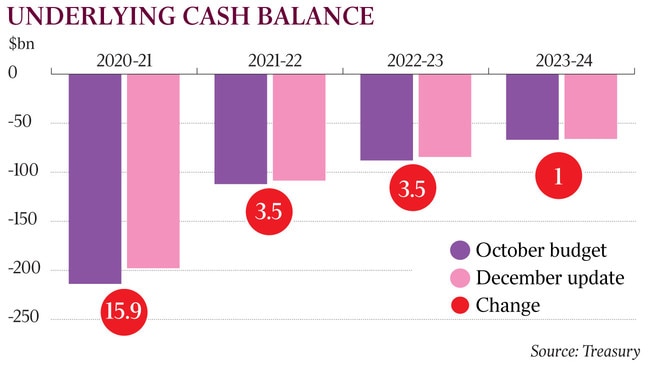

That improvement is cutting the welfare bill and the deficit, and lifting the tax take, although the underlying cash deficit is estimated to hit $198bn this financial year. If iron prices defy Treasury’s ultra-cautious estimates, which they have a habit of doing, Frydenberg will be reporting even lower fiscal shortfalls in next May’s budget, when he’ll rack up 1000 days in the job, give or take.

As well, there has been a strong recovery in household incomes, with people working more hours coupled with the abundance of taxpayer-funded payments. Even if much of the emergency help was not actually spent, there’s a savings buffer for households when income support tapers off in March. Commonwealth Bank economists calculate an extra $100bn, or 5 per cent of GDP, is sitting there ready to roll.

“This huge savings pool will provide a significant amount of support to the consumer and the economy through 2021,” CBA chief economist Stephen Halmarick said on Friday.

CBA is also at the optimistic end of forecasters, pencilling in 4.2 per cent growth in GDP next year, based on the reopening of state borders, sharp improvement in consumer confidence, recovery in the housing market and a pick-up in tourism at home. This time next year the bank expects the unemployment rate to be down to 5.75 per cent.

Last month the official jobless rate eased to 6.8 per cent and labour market experts believe some of the pieces for a sustained revival are falling into place. The participation rate is back to its pre-pandemic high. Total hours worked is now just 1.5 per cent below its level in March, full-time employment is coming back and the underemployment rate is falling.

On Friday, University of Melbourne economist Jeff Borland observed “Keynes does it again”, as JobKeeper and other payments boosted spending and kept businesses viable. The size of fiscal stimulus has made all the difference, especially in those industries that shed the most workers. Yet full-time work lags the revival in part-time employment.

“Of course, being almost all the way back to where we were in March is not the same thing as staying there,” Borland writes in a review of the latest jobs data. “The impact of the second wave of COVID-19 on labour market outcomes in Victoria demonstrates the potential vulnerability of recovery; with recent events in South Australia and NSW meaning that vulnerability should remain front of mind.”

The most worrying part of the picture is youth unemployment. “The young continue to be hit hardest in the labour market,” Borland says. “Employment of persons aged 15-24 in November remained 4.4 per cent below March, compared to 0.7 per cent for persons aged 25-64. Among the young, employment losses are still concentrated exclusively on those who are not attending full-time education.”

Reasons not to be cheerful, parts two and three, relate to wages and migration. Economists see no chance of a return to the “2-something” per cent pay outcomes of earlier times. In fact, income stagnation has set in, a mindset as much as the painful reckoning from a moribund productivity performance due to a lack of economic dynamism, job switching and market competition.

Net overseas migration has been the main driver of our GDP growth for the past decade, if not more. There was a net outflow of migrants in the June quarter (the first exodus since 1993, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics) as our borders remained closed to foreign tourists and students, and temporary visa holders made their way home.

That won’t please the tax collectors, vice-chancellors and businesses that are already reporting employee shortages.

Bringing these threads together last month was Business Council of Australia president Tim Reed, who introduced Scott Morrison to the podium at the lobby’s annual meeting

“At the BCA,” Reed said, “we believe the key question Australia faces is whether we can leverage this spirit of collaboration and re-found sense of national fairness to introduce reforms that will allow us to exit the current recession with higher productivity, leading to accelerated real-wage growth, than we entered the pandemic; or whether we retreat to our pre-COVID position of stagnant real-wage growth and real GDP being driven almost entirely via population growth.”

Morrison and Frydenberg want a business-led recovery. That’s plan A. But Reed reminded his members and special guests that things weren’t flash before the pandemic.

Business investment has been in a hole for a long time. Tax breaks are a sugar hit but companies want permanent relief, certainty around energy and climate policy, and workplace flexibility.

The Coalition didn’t so much go to water on industrial relations changes in the final week of parliament for the year, it just botched the landing with a boneheaded tactical fail. Why invest in all this “put your weapons down” hoo-ha with employers and unions and come away with a fat zero?

Colleagues commonly use two words to describe the Prime Minister and Treasurer: pragmatic and political. The third “P” of governing, policy, is not their forte. To be sure, they are good listeners. At this stage of the electoral cycle, voters have their ears rather than the shiny-bum experts who never have to face the people or have much of their salary at risk.

Frydenberg is the hope of the side for policy reformers because so much of the “productivity agenda” is in his patch or he funds it. So skilling up those young people adrift on benefits is a force multiplier, given they’ll be doing the hard yards on debt and boomer pensions.

The Treasurer is close to investors and has a natural affinity with a broad range of people in the enterprise class; unlike, say, Costello, who hobnobbed only with the top end of town, or Labor’s Wayne Swan, who was never comfortable in this milieu, Frydenberg is at home. He can, if he wants, call out their crap, resist rent-seeking.

Right now, the Victorian needs to set off the animal spirits of innovation and expansion, and watch out for excesses of market power in a landscape of failing firms. He wears his heart on his sleeve but can show mettle when under fire.

The Treasurer is a sponge for information, hyper-communicative, a social network platform made flesh, scarily energetic and not yet 50. People who tell him there’s no political capital to spend in the middle of a pandemic won’t be dealing with the big issues in five years.

Frydenberg has taken hits in the crisis. Being Treasurer is merciless; it ages and chews up people who want to take the next step. Fiscal stimulus is shopping with other people’s money, but changing the country in hard times is leadership.

In this plague year, Josh Frydenberg has been a fiscal super spreader. The Treasurer has stepped up to the role as a stimulus spender par excellence but we’ve yet to see his design of a new model for prosperity in a post-COVID era.