Narrow path won’t lead the Liberals anywhere

The former Coalition government was hopeless. What does an opposition learn from a period of government successful in electoral terms but rancid in terms of policy and leadership?

The seats they once occupied in the House of Representatives are no longer held by the party they served. Demographic changes and electoral redistributions are part of the explanation. But for one party to lose the seats once held by seven of its nine prime ministers (assuming Scott Morrison’s seat, Cook, doesn’t fall at a by-election) seems rather careless.

Menzies’ seat of Kooyong in Melbourne now is held by a teal independent. Labor just won Holt and Gorton’s former electorate of Higgins, also in Melbourne. McMahon held the Sydney seat of Lowe, which was abolished in 2009 and incorporated into the nearby seat of Reid, which Labor won at the recent election. Howard lost his seat of Bennelong at the 2007 election before the Liberals won it back in 2010. Labor won it under Anthony Albanese’s leadership this year. Abbott lost his seat of Warringah to independent Zali Steggall in 2019, and she retained it this time around. Turnbull’s former electorate of Wentworth also fell to the teals.

Safe Liberal seats reserved for potential prime ministers aren’t what they once were. Aside from Morrison, who will lick his wounds on the backbench if he even shows up for next week’s parliamentary sittings, holding Cook, Malcolm Fraser’s old seat of Wannon is the only former prime ministerial seat the Liberal Party still retains. Dan Tehan is the sitting MP.

Whatever way you slice it, the former Coalition government was hopeless. What does an opposition learn from a period of government nominally successful in electoral terms but rancid in terms of policy and leadership infighting? Not much if the remaining personnel lack the capacity to self-reflect. Even less if the party membership that preselects them isn’t reflective of the broader electorate that determines which party forms government.

For years now the guile of Liberal Party campaign strategies has overcome other deficiencies. If only Liberal MPs were as impressive as the party officials who helped them retain their seats.

Morrison is still in parliament, but he will be no help whatsoever in understanding the loss he’s responsible for. Shortly after the election, he said: “Sometimes people like to change the curtains because they just like to change the curtains.”

The fact Labor landed just two seats away from minority government obscures the fact that the Coalition is miles away from government of any sort. The Coalition must win 18 seats at the next election to govern in its own right.

It was easy enough to blame Morrison personally for this year’s election defeat. Incompetence, cruelty and failure to task responsibility were hallmarks of the Coalition government as a whole – not just its third prime minister. The defeat, however, has revealed structural problems papered over by narrow wins in 2016 and 2019; indeed, the 2013 win too.

Morrison was fond of distancing himself from the “Canberra bubble”. Yet, the scale of their election loss reflects so many Liberals live in a bubble of their own, created by their media consumption.

Political scientist Jim Walter argues that, like the original United Australia Party before it, the contemporary Liberal Party has “abandoned any philosophy that now equates with what majority opinion demands”. In sharp contrast to Menzies’ coalition-building approach, elements of the party seem proud of their narrowness. The gaps are filled with cheap populism and cultural tropes.

Unless Peter Dutton confronts this he won’t succeed in opposition. Even if he finds a way to wrest back power, he certainly won’t lead a successful Coalition government without changes.

“The resistance starts here,” Sky News’ Paul Murray declared after the election. But when polemicists such as Murray declare themselves the resistance to a Labor government, they are resisting majority opinion. That is the reality of our preferential system: Labor won a majority. To deny that and look only at the primary vote requires denial of other election wins too, such as Howard’s in 1998 when the Coalition’s primary vote fell to a historic low. That parliament delivered Howard’s signature policy – the GST.

Right-wing commentators only need tens of thousands of Australians to join their resistance to make a living. The Liberal Party needs millions of votes to be competitive in a two-party system. The Foxification of the Republican Party in the US is not a pathway that Australia’s conservative parties can afford to follow. We have compulsory voting.

Narrowcasting what constitutes a Liberal or right of centre over time will shut out more people than it will include. It will contribute further to the decline of the two-party system. The rhetoric of the Liberal Party as a broad church has become less about the broad and more about the church in recent years. The non-religious Dutton will at least stand up to that movement. The worst thing the Liberal Party can do is perpetuate the nonsense that it is now the party of the working class.

The average income of a seat conceals a lot of variation, much of which remains when analysed at the booth level – which is what instant post-election analysis often relies on. In the teal seats, the Liberals dominated among high-income earners. As political scientist Shaun Ratcliff pointed out, the Liberals win outer-suburban seats by winning the middle-class vote. The wealthiest still vote Liberal, the poorest Labor. This may still point towards a strategy of winning the outer-suburban seats at the next election, but there should be no illusions about which voters Liberals need to target.

Without Josh Frydenberg, Dutton was the only candidate for Liberal leader. Borrowing a line from former Nationals senator Ron Boswell from when he was staving off a challenge from One Nation, Dutton said: “I’m not the prettiest bloke on the block but I hope I’ll be pretty effective.” Like all Liberal leaders, he also acknowledged a debt to the party’s founder, although the further removed we become from Menzies’ leadership the less even the Liberal Party seems to understand him.

Dutton promised to reach out to “aspirational, hardworking, ‘forgotten people’ across cities, suburbs, regions and in the bush”. Just about everybody, then, which should be the starting point. Invoking Menzies’ famous line, though, was an odd move after nearly a decade in power. If they were forgotten, who forgot them?

Peter van Onselen is professor of politics and public policy at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.

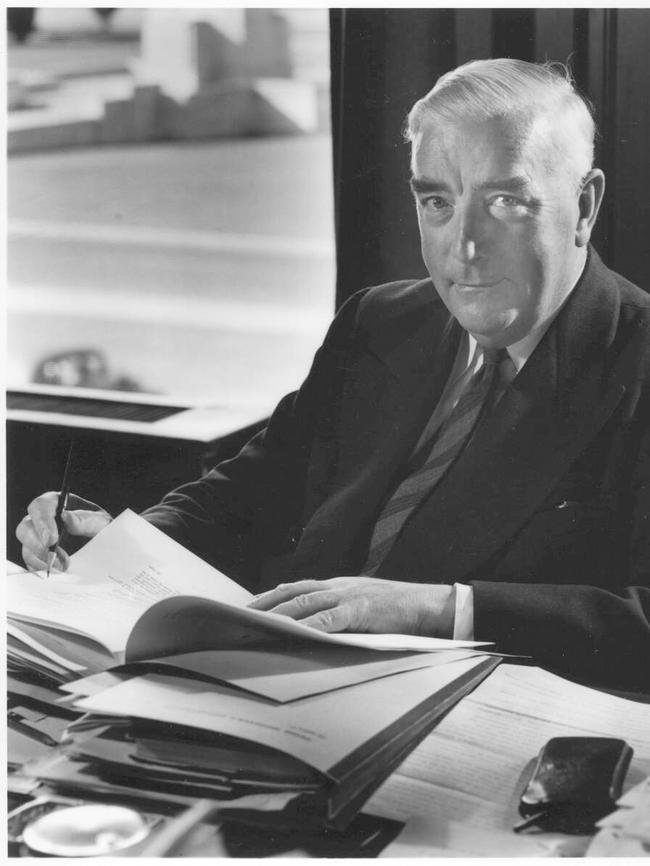

Robert Menzies, Harold Holt, John Gorton, Billy McMahon, John Howard, Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull: these former Liberal prime ministers all have one thing in common. Can you guess what it is, beyond them all being men?