My cancellation only made me more determined to speak out

When 600 Jewish creatives were doxxed, my name appeared as one of the ‘top 30’, singled out for special, more insidious harassment, deplatforming and career destruction. But the worst betrayal came from people I once admired and trusted.

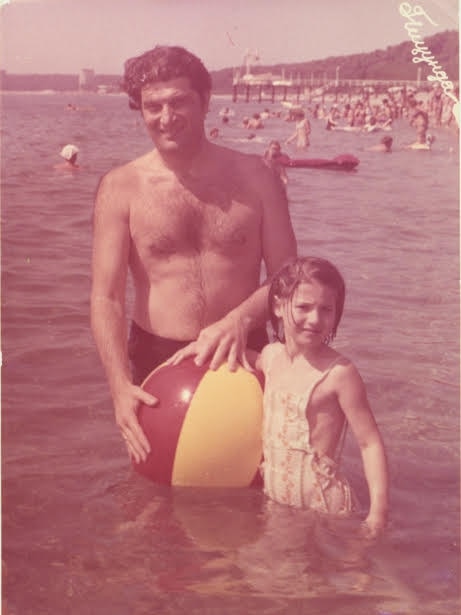

In 1987, the Soviet Union waned and my father, Eduard Sanadze – a renowned composer and founding conductor of the Georgian State Chamber Orchestra – died. He was 48. Officially, it was marked as a complication from appendicitis, a bizarre medical blunder.

But my mother and I always believed he died from losing light; his faith in humanity extinguished by betrayal and injustice.

A famous retiring violinist successfully schemed to replace him as conductor, orchestrating intrigues and betrayals against him with the help of orchestra members who had been his lifelong colleagues and friends. She enticed them with promises of jobs abroad – a dream for those trapped behind the Iron Curtain.

My father, affectionately nicknamed Dolphin for his smiley face and good nature, was deeply disheartened by these events and died within a year.

The orchestra eventually immigrated to Germany, leaving Georgia without a chamber orchestra. After my father’s death, when we searched for footage of him conducting, we discovered that his successor had bribed archivists to erase hundreds of hours of state television recordings, destroying his legacy to elevate her own.

At 10, I learned a harsh truth: life isn’t fair. Growing up under socialism, I saw mostly the ruthless and corrupt thrive – a reality not exclusive to that system but a reflection of humanity’s darker traits: power’s corruption, envy, greed and hate.

Unconsciously fearing the arrival of 48 as a fated deadline, I worked tirelessly to accomplish as much as possible before reaching that age.

After migrating to Australia at 21, I built a family, established myself as a successful children’s book illustrator and, by 33, began transitioning into fine art and sculpture.

My 2024 survey exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, spanning five exhibition spaces, was a monumental milestone and a significant recognition of my contributions to the visual arts – an honour any artist would cherish.

Through my social practice and tireless arts advocacy, I cultivated a diverse network that culminated in the creation of the Collective Polyphony Festival in September-October 2023. The festival showcased exhibitions from 10 multicultural local and international artist collectives across seven Victorian galleries, fostering and inspiring collaboration and mutual support among artists.

Rather than pursuing a customary solo show, I developed this festival as the outcome of my government-funded, two-year studio residency at the prestigious Gertrude Contemporary. Recognising the growing competitiveness and toxic politics within the broader art world, I felt compelled to create something hopeful – an initiative that could counteract these dynamics and bring people together in a positive and reparative way.

Despite receiving no funding, I successfully brought this ambitious and highly popular project to life.

Its success was made possible through my strong and positive reputation within the industry, relentless dedication and the invaluable support of volunteers who shared my vision.

On Saturday, October 7, 2023, the festival’s final public event unfolded, coinciding, unbeknown to us, with the massacre carried out by Hamas against innocent Jewish people on the other side of the world. Artists from various collectives gathered in a circle, reciting their literary works, united by art and a shared love of literature.

The festival became a poignant and symbolic final monument to collegiality and collaboration in the art world, just before its eventual unravelling. The world – and the art world – irrevocably changed overnight as the barbarity of the pogrom reverberated across continents the next day, unleashing and emboldening further unhinged hate and a doubling down of aggression against Jewish people.

With no time to grieve, no support or solidarity, the abuse and harassment of Jewish creatives like me began instantly.

On October 8, 2023, amid the shock and pain of the day, I shared blurred images on Instagram – Shani Louk’s mutilated body, the faces of Israeli women taken hostage – to honour them. I added Golda Meir’s haunting words: “If Arabs put down their guns, there would be no more fighting. If Israelis put down theirs, there would be no more Israel.”

It began with cyberbullying. An artist from one of the collectives re-shared a screenshot of my post, branding me a “snake” who had betrayed the arts community as a Zionist.

My new studio neighbour soon escalated the attack, accusing me of being a “Zionist harasser” – ironically, after an outpouring of vitriol in our shared studio chat. She then quit the Gertrude studio residency, claiming she could not share space with a Zionist. Gertrude’s studio management privately assured me they did not condone her behaviour. When I suggested leaving, they insisted I stay but avoid everyone.

Soon after, some artists, perhaps trying to rally behind my departed studio neighbour, and elevating her as a hero, fabricated further complaints and pressured management to act against me. I was already struggling with grief and shock, crying most days, keeping to myself. But after this fear crept in and I became afraid for my safety. Needing to work, I arrived early, left late, avoided the bathroom and locked my door from the inside.

Later, during one public lecture, I learned that what I was experiencing had a long and sinister history: false accusations and defamation, followed by societal isolation and, eventually, violence – patterns of anti-Semitism that have persisted for centuries.

On October 25, 2023, the National Association for the Visual Arts, our peak body, released a statement asserting that “armed attacks on October 7 by Palestinian people cannot be de-contextualised from 75 years of settler colonialism”. The group replaced Hamas with “Palestinian people”, claiming Western media “demonises the resistance of the oppressed”.

The statement by NAVA, as an industry leader, set the stage and a pattern for a wave of vitriol and destruction of the art world that followed. Within a month, galleries and art institutions began succumbing to the immense pressure from select artists, with almost every artist-run space issuing statements about the “genocide in Gaza”.

The pressure spread across the arts, with institutions from theatre, music, film, dance, festivals, fairs and competitions quickly caving to complicity, purging Jewish creatives, board members and philanthropists from their ranks.

At Gertrude, artists demanded that management release a statement as well. The board asked artists to submit their opinions.

In response, I drafted a letter titled Death of Art, pleading for neutrality. I wrote: “It is noteworthy that galleries and artist-run spaces, once considered safe and diverse havens for artistic experimentation, are now compelled explicitly to affirm their commitment to inclusivity but nevertheless exclude divergence of perspective on matters of extraordinary complexity and importance.”

I continued: “In September, I initiated the Collective Polyphony Festival, dedicated to celebrating the diversity of artist collectives.

“While committed to teamwork as a member of two artist collectives, I vehemently oppose participating in an art world that promotes a single team and speaks with only one voice, even if it aligns with just and progressive values.

“Such a monolithic approach, lacking polyphony, transforms art into something resembling a religion or propaganda, signalling the demise of true artistic expression.

“This not only marks the demise of art but also presents a potential threat to our broader democracy, safety and liberty. Galleries serve as forums for numerous voices, not as a singular mouthpiece. They should be safe spaces where multiple perspectives converge – an embodiment of the ideal of artistic freedom and expression for every voice.”

It seems I was the only studio artist to oppose the motion for a public statement on “genocide”.

Gertrude’s board ultimately decided not to issue a statement, citing its government funding, but it assured me that compliance would be demonstrated through its future exhibition programming, which has since clearly mirrored the prevailing orthodoxy of other art institutions.

The most troubling trend has been not only the anti-Semitic behaviour and shared statements or false narratives by artists, academics, cultural leaders and institutions – though those were deeply concerning – but the consistent and oppressive peer pressure to conform and “speak up” about the “genocide”, with silence equated to complicity. This pressure created a climate of fear, forcing compliance under threat of cancellation or ostracism. The so-called silent majority was simply fearful and retreated into self-censorship, avoiding social media or, in some cases, shutting it down entirely to evade scrutiny.

This authoritarian cultural conformity in Australia now feels as oppressive, if not worse, than what I remember from the Soviet Union.

By late November 2023, broken and isolated, I was invited to join a Jewish creatives group. It felt like a lifeline. I didn’t know then that there were as many as 600 of us from across the arts and Australia-wide. The group’s busy feed was for sharing news, offering moral support, sometimes writing objection letters and signing petitions – exercising our democratic rights.

But even that space was violated. A 900-page transcript of our group chat was downloaded and leaked by a reporter from The New York Times. On January 30, 2024, intense and widespread doxxing ensued. In addition to the ongoing attacks on a smaller, selected group of us – a “top 30” hit list – the details of all 600 members were shared with an audience of about half a million. This was a “Jew list” created for the purpose of intimidation.

It was midnight, after my fateful 48th birthday, and unbelievably – as I had feared since childhood – the premonition I’d long held was coming true.

My name appeared as one of the “top 30”, singled out for special, more insidious harassment, deplatforming and career destruction – simply for being part of the Jewish group, for having a public profile and for representing dissent from within, which the doxxers believed deserved a unique kind of punishment.

When they found little in the transcript to use against me, two former friends escalated things by leaking private messages. In one, written the day after October 7, I called Hamas “animals” for their atrocities. In another, I sarcastically remarked on a photograph of suspected Hamas operatives, arrested in an evacuated area of Gaza and wearing only their underwear, presumably to show they were not carrying weapons, that they seemed well-fed after looting humanitarian aid.

These became my supposed chief crimes, rebranded as “fat-shaming Palestinian resistance” (not Hamas) to paint me as hateful and racist.

This distortion of meaning mirrored NAVA’s own instructional statement, where the word Hamas was routinely replaced with “Palestinian people”. A peak body tasked with creating safety for all artists became instrumental in erasing rights and paving the way for harassment and bullying of individuals such as me.

Furthermore, emboldened by this, many members of this community personally and systematically pursued hounding, doxxing and defaming me in several public social media posts from esteemed art institutions across the past 15 months, ensuring my complete destruction and eventual erasure as an artist.

The worst betrayal came from people I once admired and trusted – people I thought were friends. More than 500 former friends, colleagues, industry leaders and academics unfollowed and blocked me on social media in what appeared to be a co-ordinated effort. They circulated the doxxed information and flooded social media with nasty comments, like schoolyard bullies revelling in their toxic power. I will never unsee their real faces or forget their cruelty.

Things grew even darker from there. On January 31, on arriving at my Gertrude studio, I was unceremoniously interrogated by the management. The following day, I received the message that I would no longer be able to access my studio as my presence was deemed inappropriate and the organisation had become a site of “stickering” protest and relentless social media harassment.

At the same time, my commercial gallerist, in tears, told me she could no longer defend or represent me. Fearful for her business and safety, she, too, had become a target of the same harassment.

My health deteriorated, leaving me bedridden, as if paralysed. I was constantly summoned by Gertrude management for meetings, but I simply couldn’t move. A board member called and offered to pay for my move and to find me a new studio “for my own safety”. I saw it as a bribe, an attempt to rid themselves of me, so I dug my heels in.

In a last-ditch effort to salvage some dignity in this fractured art world, I wrote a letter to management, outlining the events of the previous four months. I asked them not to play along with the book of anti-Semitism, a stain they would never be able to erase from their reputation. Instead, I gently urged them to set an example as industry leaders and pave the way for coexistence and negotiation.

As if agreeing to talk on those terms, I was lured into a meeting and asked to bring a support person. But it felt like a trap. Set in the gallery, with a backdrop of spirituality-themed art, the space was suddenly arranged like a tribunal, complete with a table of prosecutors, almost resembling Soviet-era political trials.

I was mostly silent throughout, as they told me the organisation was at breaking point from pressure on all sides, the artists, the board and the staff. They emphasised that, during the meeting, my ethnicity and history could not be mentioned and, oddly, they repeatedly told me I could not be a victim.

I was accused of being a harasser, a bully and a racist, and was advised to forfeit my studio residency immediately and voluntarily, as it would be in my best interest. They warned that if I didn’t comply, further defamatory information would likely be released about me by unspecified individuals online and through other channels.

When they asked why I had stopped volunteering to move out, I explained that, as a long-time arts advocate, I initially didn’t want to damage Gertrude’s reputation. I told them if they had approached me humanely, instead of bribing or threatening me, I might have been open to a solution.

They seemed to expect tears and my immediate resignation, but I was simply numb with shock. I left the meeting and immediately sought legal advice.

My lawyer soon after discovered from Gertrude’s lawyers that their claims of “harassment and bullying” against me were based on my two polite open letters to the management – Death of Art and the one in February, in which I asked the leadership to find a pathway to coexistence.

When I returned in March to pick up my sculptures with the National Gallery of Victoria crew, as approved by management, I arrived only to find the front of the building defaced with the words “Zio Dogs” scrawled in giant graffiti, an act of intimidation aimed directly at me. Security camera footage recorded an unidentified hooded individual carrying out the vandalism overnight.

It was yet another chilling amplification of the harassment I had already endured.

Despite the escalating danger, after many conversations and doubts about whether to postpone or proceed, the decision was made to move forward with my NGV survey exhibition, launching on April 12, 2024, albeit with a slight delay, limited promotion and heightened security. The decision was made not to speak publicly or to the media, or to press a case against Gertrude.

Instead, I chose to move out quietly, prioritising the platforming of my art and the significance of my exhibition. The aim was to avoid violent protests at the gallery or the need to shut the exhibition down entirely for safety reasons.

Despite its subdued nature, the exhibition attracted a meaningful audience and was a success, deeply moving hundreds of attendees who contacted me privately, sharing their own experiences and reflections. The exhibition resonated deeply with the audience, reflecting the complexities of this time.

Ironically, my sculpture and installation work had long delved into historic themes rooted in my family’s experiences, my own journey and the history of the country I come from – totalitarianism, propaganda, cultural and political oppression, war, regimes, ideologies, persecution, imperialism and the Holocaust. These themes, once confined to the past and explored through my art, were reanimated in my life, violently intruding into my personal world in a deeply shattering way. My art, in this moment, became my life.

The anticipated protests never materialised at the NGV as the Melbourne art world shifted tactics, quietly erasing me and my work through lies, rumours and ongoing online harassment at every opportunity. Those who secretly attended my show refrained from sharing posts, self-censoring out of fear of persecution, as I had become “the untouchable”.

I learned that the cancellation process has three stages: harassment, deplatforming and posthumous erasure. In a gobsmacking discovery, the University of Melbourne has recently removed a celebratory alumnus Instagram post about my NGV exhibition. My erasure achieved.

Like socialism, activism runs the risk of becoming a pursuit of power disguised as moral virtue. The appeal of socialism has always devolved into a tool for imperialism and oppression, driven by human failings. Fixing systems alone isn’t enough; we must confront our individual flaws – our hunger for power, envy, hate and greed – which demand a personal reckoning, a far more challenging task.

Human survival relies on the light within us – faith in each other and collaboration, amid our flaws. When my father lost his light, he lost his life. Though the darkness looms, I hold on to the belief that the light within us – fragile but enduring – is what makes us human. Without it, we are lost. I refuse to let mine go.

Fifteen months later, I find myself standing amid the charred ruins of the Adass Israel Synagogue. I am retrieving burned remnants of furniture for a forthcoming sculptural work, reflecting on the unsettling parallels between the synagogue’s destruction, my own and countless others. All reduced to ashes, consumed by forces beyond our control.

And yet here I am – gathering the pieces, trying to rebuild, create again, and allow the art to speak as a witness once more.

And there is light. I am preparing to open a new gallery, Goldstone Gallery, dedicated to “uncancelling” politically censored, silenced and muted voices.

The gallery launches next month with its inaugural and important solo show, Navalny, marking the one-year anniversary of Alexei Navalny’s death in a Russian gulag. The exhibition will feature the work of renowned photojournalist Evgeny Feldman, who chronicled the Russian opposition leader’s life for more than a decade.

Rather than focusing on lawsuits and complaints, I am choosing a proactive and positive path steeped in art.

Goldstone Gallery is advocating for, and seeking, institutional policy changes to reintegrate, create safety for and support Jewish creatives across Australia, setting a precedent for a course correction towards a more just and inclusive cultural landscape.

Arbitrarily cancelling people has become an aggressive policy of the art world. But hate, bullying and mob rule destroy lives, livelihoods and businesses. We are not mere digits or words on a screen to be erased; we are humans with long and complex histories, each with an important agency and story. No one – least of all a mob – should wield the power or make the judgment to erase someone’s existence.

Nina Sanadze is a Jewish sculptor from Melbourne.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout