Murder lab ‘train wreck’ in Shandee Blackburn case

Forensics should have solved Queensland woman Shandee Blackburn’s murder back when she was killed in 2013. Instead, the evidence is ‘train wreck’ that goes well beyond just her case.

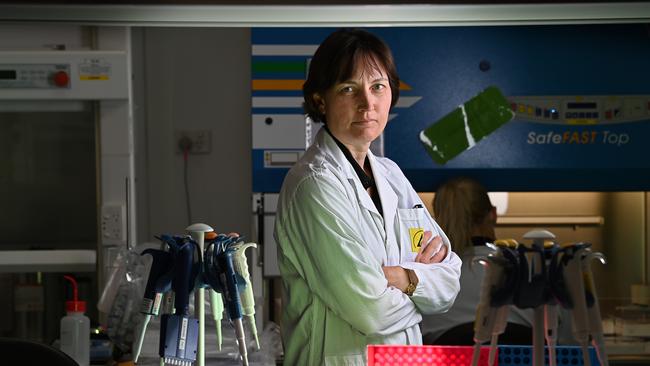

Renowned forensic scientist Dr Kirsty Wright knows well the importance of putting aside emotion during her sometimes harrowing job.

Wright is an expert in following a trail of forensic clues to solve mysteries, the woman you call to identify human remains in national disasters and battlefields – or to crack tough criminal cases.

Her razor-sharp intelligence, skills and work ethic have seen her acknowledged as one of the best and brightest in her field, making her in demand from agencies ranging from police services to the armed forces.

Dispatched to Thailand following the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, the unfathomable tragedy that claimed almost 228,000 lives in 14 countries, she would flick a mental switch to turn off her emotions.

SHANDEE’S STORY PODCAST | New episode out now

It helped mitigate the personal impact and to stay focused as Wright, DNA team leader of the international effort to identify victims, drove into the Thai mortuary and passed pictures of dead and missing children and adults.

The eyes in those pictures would follow her, as if asking when she was going to find them. She saw her remarkable contribution as just a way of helping out.

Sixteen years later, the tough-as-nail forensic biologist is helping on another task with extraordinary dedication, teaming up with The Australian’s Hedley Thomas on his investigative podcast series Shandee’s Story. Their aim is to get to the bottom of why a savage stabbing murder of a young woman walking home from work in Mackay, Queensland, remains unsolved.

Her mental switch has been flicked again, so it might be surprising for some to hear how, with her dispassionate and measured scientist’s cap on, she describes the forensic evidence she has been studying for months.

In Wright’s view, forensics should have solved Shandee Blackburn’s murder back when she was killed in 2013. Instead, that evidence is a “train wreck”, she says, that goes well beyond impacting just Blackburn’s case.

“What I’ve found is quite unbelievable,” Wright said this week. “And I think that what we’re seeing with Shandee’s case may be the tip of a very large iceberg.”

Wright is convinced the police investigation into a woman’s murder has been seriously compromised by a litany of forensics failures in Queensland’s government-run laboratory.

It is an opinion based on her years of experience, including time spent in the very lab she is now questioning, and her examination of hundreds of pages of documents from the homicide investigation and court proceedings.

She is sure other cases will have been compromised by the same major errors and problems. Until there is a thorough and independent inquiry, there will be a threat of innocent people being jailed or the guilty walking free, she says.

Wright is the former head of Australia’s national criminal identification DNA database, and holds a high-level Australian government security clearance.

As highly experienced legal figures affirmed this week, she is no grandstander and her opinions carry significant weight.

Wright is convinced a spate of critical problems distorted the government lab’s testing, thwarting its ability to get DNA profiles from crime scene evidence that had been gathered by police.

She is confident this is linked to the introduction to the lab just weeks before Blackburn’s murder of a new computer program for DNA profiling called STRmix, and a new DNA profiling kit called PowerPlex 21.

In brief, her discoveries include the lab’s failure to detect trace DNA from the main police suspect, John Peros, on any of the surfaces of his own dirty Toyota ute. The vehicle was almost 20 years old, and Peros’s DNA should have blanketed the vehicle.

Next, there’s the inexplicable failure to detect DNA in a sample taken by police from a fresh pool of blood. It was from the crime scene at Boddington Street, where Blackburn stopped moving after suffering 23 wounds in a vicious attack with a large knife.

Then there’s the lab’s failure to detect DNA in a high-priority sample taken by police from Shandee’s left forearm that would have at the very least contained many hundreds of her own skin cells.

Wright lays out the implications with logic and precision: If a lab can’t get DNA profiles from a fresh pool of blood, or from the victim’s forearm, or trace DNA of the main suspect from his own car, how can it be relied on to find trace DNA from the killer? What else has the lab missed?

These problems should have been obvious to the lab at the time. Worse, they had proof something was going badly wrong because, 16 months after finding no DNA on Blackburn’s forearm, the lab did more testing on the same sample and this time found mixed DNA from multiple people.

Wright says this should have been the moment the penny dropped in the lab.

“That’s critical because it shows that at the time a majority of the samples from Shandee’s case were being analysed, there were flaws in the system. This sample proves that. But further, it shows that the laboratory knew that.”

It’s why she says that at best the lab has been negligent, and at worse it has been obstructive of police investigating a murder. Disappointingly, the DNA eventually detected in the left forearm sample couldn’t be interpreted; it was effectively useless for police.

Wright’s list goes on. In a jaw-dropping 17 instances, the lab had wrongly linked people to crime scene items.

A laboratory scientist had to officially inform police that the supposedly certain results in each of the cases were wrong.

Wright discovered this in the forensic register, the repository for all the scientific and technical analysis in the case.

A single error should ring alarm bells. To have 17 is “completely unheard of”, Wright says.

The errors, problems and inexplicable results she is seeing from the lab in the murder investigation are unprecedented in her professional opinion.

It has led her to a conclusion that should be sending shockwaves through the network of judges, prosecutors, defence lawyers, defendants, victims and their families who rely on expert, independent forensic scientists to deliver fair outcomes: the official government lab’s results cannot be trusted.

Blackburn family lawyer Kristy Bell says the implications for the legal system are “astronomical”, akin to the “Lawyer X” scandal that has rocked Victoria.

“We really have no idea what the potential is for the impact on other cases,” Bell said this week, backing the family’s call for immediate retesting in Blackburn’s case in a new lab, and an inquiry into the state-run lab.

Blackburn’s mother, Vicki, and sister, Shannah, have been stunned by the forensics failures, but also now have a new reason to believe there can be a proper resolution in the case.

Detectives from Operation Lima Zimzala had been baffled by the forensic evidence.

They were convinced that Blackburn’s former boyfriend, Peros, was the killer, but nothing in the forensic evidence linked him to the crime. None of her blood or DNA was found in the car Peros was alleged to have driven immediately after the murder.

Likewise, none of Peros’s blood or DNA was found on Shandee’s body or at the crime scene.

He denies any involvement.

The investigations by Wright and Thomas could explain why there was no DNA linking Peros to the murder – or alternatively, why someone else was not revealed as the killer.

As the Shandee’s Story podcast details, police investigators from Operation Lima Zimzala did question the lack of forensic evidence in the case at the time, with homicide detective Scott Furlong’s increasing frustration over the absence of DNA obvious in the official running log.

Furlong has since retired from the Queensland Police Service. He confirms that there were times when he was concerned that DNA profiles weren’t being found in police samples.

“However, they’re the experts and they tell me differently, that ‘no, that’s right, that’s the results and that’s the end of it’,” he says.

He says he would argue the point, but that he’s no scientist, and has no expertise in the area.

The absence of Peros’s trace DNA in samples from his own car was “remarkable”, he says.

“You just think, what else could there possibly be? We certainly were at pains to have explanations and things re-examined.”

Queensland Health failed to acknowledge receiving 15 detailed questions about the problems in the Forensic and Scientific Services lab until being contacted again later by The Australian for confirmation.

Given six days to reply, the department did not provide any response or communication. Followed up again after the deadline lapsed, a spokeswoman said there would be no comment due to privacy issues and because of the extent of work it would involve to answer the questions.

This response only strengthens Wright’s position that the errors and inconsistencies in the lab cannot be examined internally.

She and other scientists have been concerned about the culture and processing in the lab for years.

Back in 2015, even Queensland Health acknowledged the lab had problems with its STRmix computer software for DNA profiling. It had resulted in the wrong “likelihood ratios” – the probability of a DNA match – being issued at least 24 times, including in the rape and murder of a pregnant woman, Joan Ryther, as she walked to work.

The department blamed a “minor miscoding issue” – but software co-creator Dr John Buckleton said the Queensland lab hadn’t bought the manual.

Australian jurisdictions were given the software for free but had to buy the manual. “Every other lab has bought it,” Buckleton told this reporter at the time. Queensland Health said it had simply declined to purchase additional manuals for the new version.

Wright says there were extremely talented scientists in the lab in 2013, and believes they must have seen the obvious errors.

“Did they alert lab management to these serious issues and their concerns were ignored? If scientists from the QHFSS DNA laboratory know the answer to this question they can come forward – they can contact me or Hedley in confidence.”

The scientific community should be deeply concerned until the matter is investigated, she says.

Anyone with information about the murder of Shandee Blackburn can contact Hedley Thomas confidentially at shandee@theaustralian.com.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout