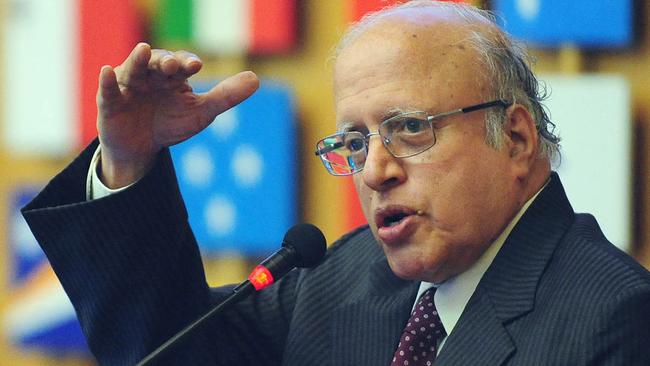

MS Swaminathan’s high-yield rice and spud hybrids were gamechangers

Unassuming researcher MS Swaminathan changed the way essential crops are grown across the world – and transformed economies.

OBITUARY

Monkombu Sambasivan Swaminathan Agronomist

Born Madras, British India, August 7, 1925; died Chennai, September 28, aged 98.

Florence Nightingale did not just invent modern nursing and help make basic sanitation part of everyday life; she also campaigned for the British to help famine-proof India. She believed famines were avoidable, not a view commonly held back then.

Nightingale saw the bouts of starvation that cursed India, and claimed millions of lives, as a management issue. She wrote in 1878: “We do not care for the people of India … Between five and six million have perished … How can we realise what the misery is of every one of those figures: a living soul, slowly starving to death?” She described the 1876 Madras famine as “worse than a battlefield” – quite a comparison for a woman who made her name on the bloody acres of Crimea in the 1850s, when war claimed 450,000 people.

India, like Australia, is always a land “of droughts and flooding rains”. Right now 30 per cent of India in drought. Weather-induced famine there has been part of life forever and, despite the British responses to the problem, this continued well into the 20th century. The Bengal famine of 1943 claimed three million lives while smaller bouts of starvation occurred until 1966.

But by then a change was under way in India and across the world that has saved untold millions of lives and transformed economies, largely orchestrated by one modest man: MS Swaminathan.

Swaminathan’s father was a surgeon but died when the boy was 11. His uncle paid for Swaminathan’s education and he completed the equivalent of the Victorian Certificate of Education by 15.

The extended family was reliant on income from rice, coconuts and mangoes, and Swaminathan was keenly aware that their income collapsed in droughts, floods or with plagues of pests. At university he achieved degrees in zoology and agricultural science and became fascinated by genetics and plant breeding, and in 1949 was offered a UNESCO fellowship to study genetics in The Netherlands. There he worked on changing the potato. Spuds had helped the Dutch survive the war, but they weren’t enough of them. His research would make them hardier in the cold while protecting them from parasites.

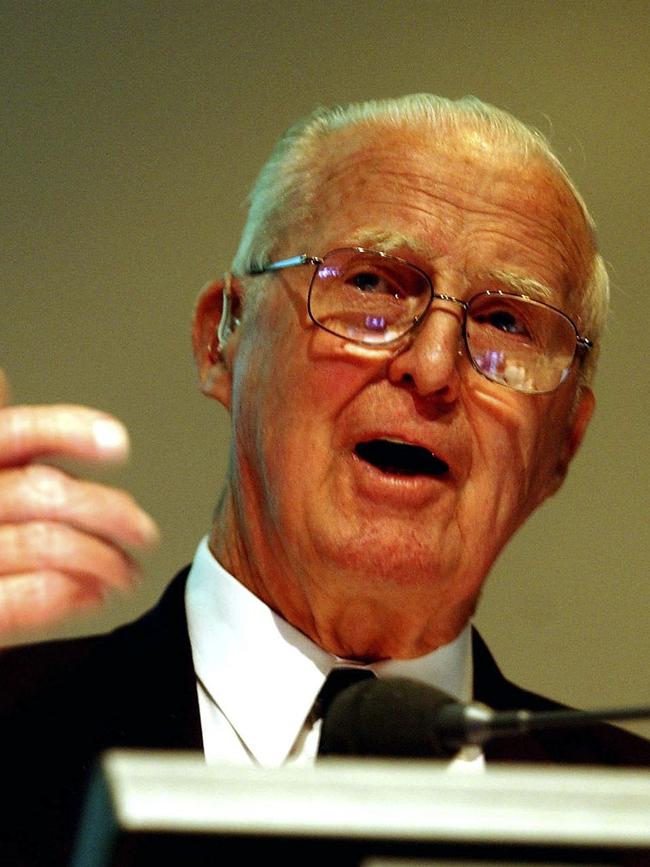

He completed stints at the universities of Cambridge and Wisconsin, impressing everyone with his brilliant work, but he wanted to return home to make a difference to people for whom food was life and death. He worked on hybrids of wheat and rice, India’s most important crop. At the time, India was a large-scale food importer. He partnered with American scientist Norman Borlaug to interbreed international varieties of wheat, creating a high-yield crop that tested well even if farmers were reluctant plant them.

Further modified for local conditions, the new variety won growers over. The two men had begun what would be called the global green revolution, born of their research, new fertilisers and then popular pesticides, some of which would later become contentious, even outlawed.

Having been credited with saving a billion human lives, Borlaug won the 1970 Nobel Peace Prize but wrote to his Indian colleague giving him much of the credit.

Rice feeds 60 per cent of Indians. When Swaminathan left his homeland 70 years ago, its rice production was about 20 million tonnes annually. Last year it was more than 130m tonnes.

While serving in senior government roles from 1972, starting as director-general of Indian agricultural research, he set up technical training programs and encouraged the regions to study the separate meteorologic patterns while promoting water conservation. He spent the 1980s as boss of the International Rice Research Institute and in 1987 won the inaugural World Food Prize while vice-president of the World Wildlife Fund, winning praise from US president Ronald Reagan for his leadership in sustainable development.

Swaminathan said the green insurgency had changed Indians’ attitude to agriculture – about 70 per cent live rurally – to “one of pride and confidence rather than one of despair and doom”. And he defended his country’s social structure in which most family-owned farms were down to just more than a hectare. This was half what they were 50 years ago, but there are twice as many farmers – changes that could have resulted only from Swaminathan’s breakthroughs.

India’s population was about 350 million when he left university. Now it is more than 1.4 billion. After feeding them, Swaminathan’s research means his country, 14 years ago the fifth highest rice exporter, behind Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan and the US, this year will export 20 million tonnes, more than double second-placed Thailand. That’s worth more than $11bn. And he conquered famine. Who needs a Nobel prize?

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout