Mountains to climb: challenge of the Albanese ascendancy

The remarkable election result signals long-term political and cultural ramifications.

Australian life and politics have entered a new experiment. It is a 2020s Labor ascendancy based on Anthony Albanese’s leadership, likely to last for the rest of the decade, with Labor now positioned to decide how far the nation’s economic, social and strategic foundations will be redefined.

The Albanese ascendancy needs to be understood – it is wide, not deep, but likely to endure because it reflects structural and cultural changes in our life. This looms as the most influential Labor government since the Hawke-Keating era, but that was 40 years ago and Albanese Labor, unsurprisingly, is far different from that brand of dynamic centre-right reformism.

The election offers many pointers, some contradictory, to our future. Albanese projects three identities – as successful battler, as true Labor and as a modern progressive – a leader who won’t get ahead of himself, who fosters stability, unity and down-to-earth pragmatism.

Yet Australia at the election has moved to the left in economic and social terms. With the left shading the right in internal power, Albanese’s destiny is now to show how a centre-left Labor government can deliver sustained success for Australia in the 2020s.

The country hasn’t been here before in the lifetime of today’s Australians. Can a long-term centre-left national government manage the multiple challenges ahead? It is an experiment because Labor has changed and the country has changed. The post-Covid shift in Australia’s outlook helps Labor.

The party runs an economic model perhaps described as state paternalistic capitalism, an energy transition dedicated to the utility of renewables, social policy that locks in constituencies through government direction and spending programs, and a creeping agenda of cultural progressivism.

Whether the electorate will underwrite this framework over time is highly dubious. Albanese seeks to govern from the Labor centre and stick to his election mandate. How Albanese evolves as a pragmatic adaptor remains to be seen. Regardless of his majority, Albanese as PM confronts a daunting task.

Consider the paradox of the election: Albanese won a sweeping victory when much of the country was unimpressed by his first term in office. A week before the election Newspoll said only 39 per cent of people believed the government deserved to be re-elected while 48 per cent said someone else should get a go.

That’s a dissatisfied society. The further evidence came when people were asked whether the Coalition was ready for government, with 62 per cent saying they were “not confident”. The public was sceptical of both Labor and the Coalition but far more distrustful of the Coalition.

Former Liberal minister and party director Andrew Robb said of Labor’s flawed record: “Three years of broken promises on power prices, living costs and mortgages, the housing crisis, uncontrolled immigration, the neglect of national defence, the loss of nearly a year of governing with the hugely divisive voice campaign, a forecast of 10 years of budget deficits, the spread of violence and the wave of anti-Semitism, recalcitrant unions, burgeoning red and green tape, and the related failing ‘renewables plus storage’ experiment.”

If Albanese is to succeed, his second term must improve on his first. That is the essential test; more of the same won’t suffice. Treasurer Jim Chalmers said post-election that the second-term economic priority is “productivity without forgetting inflation”. That is the pivotal declaration – only higher productivity can underwrite higher living standards. That’s the issue that will make or break the Albanese government.

It is time for Chalmers to bring out his inner Keating – get tough and impose a productivity-enhancing agenda on the cabinet. That means directing his persuasion inside the cabinet, not just outside. Does Chalmers possess the authority and will to do this? It could be the decisive question for the second term.

Unless Chalmers exercises the authority as Treasurer that typified Paul Keating and Peter Costello, Labor’s ability to turn its majority into policy gains will fail and that means, in the end, it will fail politically.

Albanese is Mr Engagement. “I build relationships with people,” he told Sky News. It’s a long list – unions, business, civil society, global leaders, King Charles, and Donald Trump next in line. But Albanese as PM is neither a transformational figure nor a policy innovator. Over to Chalmers.

The left wing has never been as potentially powerful since World War II, inviting the question how Labor will use the ascendancy it has won. Here’s the test: PMs with big majorities are tempted to do what they want, not what the country needs. That’s another make-or-break test for Albanese.

He has a strong political strategy. It was apparent in the campaign and even more last week.

Albanese talked up his second-term agenda based on practical progressivism – Labor as the party of opportunity, of private investment, of the energy transition, greater housing supply and density, universal services represented by Medicare, trade diversification and the embodiment of multiculturalism, supporting the Chinese and Indian communities, elevating a nation based on respecting people “of different faith, different ethnicities, different backgrounds”. Labor’s skill is projecting its brand, whether valid or not.

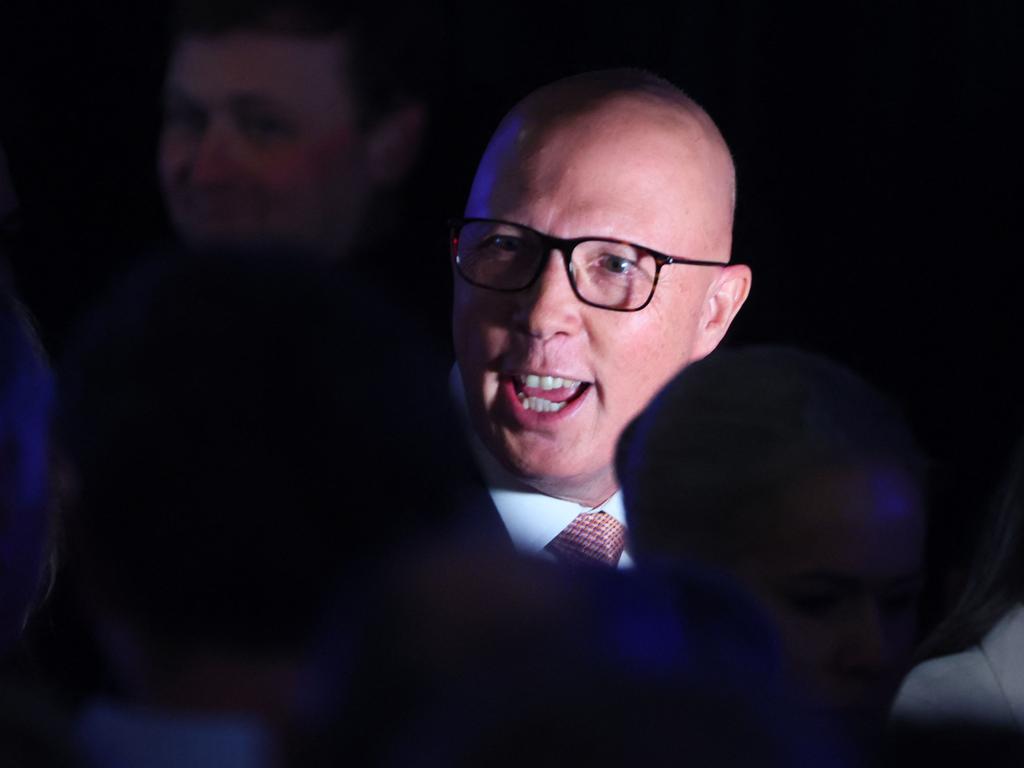

Albanese’s opportunity is blue skies. In one blow he has smashed the Liberal Party for years, engendering a crisis of identity, while he has reversed the advance of the Greens. The defeat of both Peter Dutton and Adam Bandt in their seats is an extraordinary Albanese triumph but highlights an Australian disposition – the people distrust Greens extremism and demand Liberal leaders with empathy. Big lessons there.

The Albanese working rule is: “No one left behind, no one held back.” That’s non-ideological, it’s about hard results. He sees that rule as compassion for the less well-off and aspirational for the middle class. Influenced by the abject failure of the US Democratic Party against Trump, Albanese wants to govern for the whole country, not just his loyal constituents. Indeed, that’s the logic of his election victory. But beware – just watch the demand for spoils from Labor’s constituents.

Consider these challenges. Labor needs an economic growth strategy. A post-inflation boost isn’t enough. It must impose fiscal control when its MPs will demand the opposite. It cannot allow the income tax burden to keep escalating. It is trapped with an energy policy that guarantees steadily increasing prices. Its tax and IR policies undermine private investment, yet private investment is essential to recovery. Its bias to the public sector is an electoral plus and an economic minus. Its red and green tape suffocate initiative and enterprise. It needs public sector reforms, notably in health and the NDIS. It is caught with a defence policy obviously inadequate in its spending and riddled with procurement inefficiencies. And its ability to realise its AUKUS commitments is in doubt.

In the disruptive world of the 2020s old-fashioned, pre-Hawke-Keating policies won’t deliver for Australia. While Paul Keating attacked Albanese for his failure not to protect right-winger Ed Husic in cabinet, Keating’s critique of the Albanese government’s first term is far more significant and direct – he thinks too many of its core policies are misguided, economically and strategically, a critique the government essentially dismisses.

The trap for Albanese lies in the distinction between a wide and deep victory.

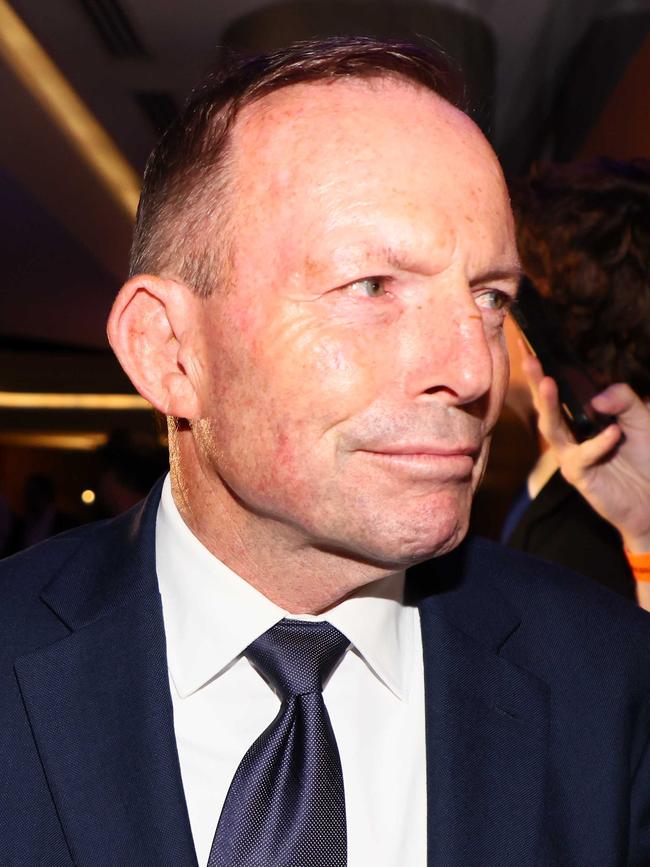

He scored gains against the Coalition and the Greens, with Labor to finish with seats in the low 90s compared with the Coalition in the low 40s. Indeed, Albanese’s two-party-preferred vote was higher than Tony Abbott got when he won office in 2013, as well as higher than Gough Whitlam, Bob Hawke and Kevin Rudd in their inaugural wins.

While an astonishing victory, it is driven by two elemental forces. First, the Australian people are more volatile in their voting, able to reward and punish more freely than before because Australia, in cultural terms, is a more fractured nation. That is only likely to intensify. Cultural diversity breeds political fracture. Labor won’t be immune.

Second, the result arises more from Labor’s status as the “least worst” option for much of the voting public. Labor’s poor primary vote of 34.7 per cent shows only one-third of the nation really prefers Labor, but that converts into a two-party-preferred vote of a mammoth 54.61 per cent achieved through the preference system because people voting for other parties still preference Labor as they vote down the card.

In this election Albanese was seen by many voters as less offensive than Dutton or Bandt. That Dutton and Bandt lost their seats illustrates the point. Voters rejected their brand of strong partisanship. By contrast, the nickname “Albo” rings with Aussie familiarity. The fact is even people who dislike Albanese still preferenced him. He was seen as the leader “you distrust the least”. But securing such a victory on preferences points to a degree of conditionality for Labor.

Albanese defines Labor as the party of the future – and the party of a changing Australia. His aim is to denigrate the Coalition as the party of an Australia that is dying. The reality is that Australia has changed immensely since Abbott’s 2013 victory. The shift has been towards a more progressive set of values – and the story of the decade, the voice aside, has been the Coalition’s failure to project its own liberal and conservative values in this contest. Coalition figures seem to lack the language and the cultural understanding to meet this challenge.

The Coalition is in trouble with four dominant centres of Australian life: the tertiary-educated professional and elite class; women, and particularly professional women with influence – witness the teals story – with some evidence women were more hostile to Dutton in 2025 than they were towards Morrison in 2022; the youth vote, with polls showing young people under 34 are more likely to vote Greens than Liberal, and; ethnic communities, where an increasing electoral challenge arises from the Chinese, Indian and Muslim communities and their expectations of the main parties.

As the 2020s advance, Australia will become more urban, more educated, more shaped by female influence, more alert to the under-40s generations and more multicultural. The Liberals need to change their mindsets and their cultural norms to respond.

For years a great impediment to bold government has been a narrow mandate. The last election when a prime minister won a strong mandate was Abbott in 2013 – and that didn’t work well. For a decade the elections of 2016, 2019 and 2022 delivered extremely narrow wins for Malcolm Turnbull, Scott Morrison and Albanese respectively.

Now that cycle is broken; another empowered executive has arrived. Albanese has a command no PM has experienced since John Howard after the 2004 poll – a big majority in the House of Representatives, a Labor-Greens majority in the Senate, Labor governments in four states, and the Coalition in a condition of unprecedented weakness.

The pivotal issue therefore becomes: Will Albanese succeed in aligning Labor as the culturally dominant party of the 2020s? The related question is: Will Labor shift the balance of our politics from being centre-right to being centre-left? Don’t think it can’t happen. There are no guarantees about the relevance of parties.

In his concession remarks, Dutton said: “I love this country and have fought hard for it. We have been defined by our opponents in this election, which is not a true story of who we are.” Yet this is exactly what happened at the 2022 election. The Loughnane-Hume report on the 2022 defeat said: “The Coalition had lost control of its brand, with the parties and their leaders being defined in the public’s mind by our opponents.”

For however long the Liberal Party cannot explain and define its values to the Australian people, it faces defeat and growing irrelevance. As Redbridge strategy director Kos Samaras said in the Financial Review: “Unless it redefines who it is, who it speaks for, and what kind of Australia it wants to shape, it will remain locked out of the suburbs, cities and communities where the country’s future is being written.”

Can the Liberal Party unite after its 2025 wipe-out? The omens aren’t encouraging given a bitter leadership contest between Sussan Ley and Angus Taylor. The worst mistake the party can make is to sink into factional warfare between conservatives and progressives or moderates. The rebuilding of the centre-right will require an outward-looking Coalition that reaches out to the community and recruits intellectual backing and develops networks from many centres of Australian life.

The Liberal Party suffers from cultural denigration now entrenched across much of the nation’s educated, artistic, professional and media ranks. Reactions to Dutton’s defeat typify the problem. Take two examples – the near automatic reflex that Dutton lost running an aggressive right-wing agenda and focused on culture war issues.

Since Dutton did neither – indeed he did precisely the opposite – such views testify to a deeper problem: a toxic view of the Liberal brand that seems to transcend whatever it does.

In this campaign Dutton was excessively cautious and seemed intimidated by Labor. He endorsed most of Labor’s spending agenda, notably on Medicare. He declined to tackle NDIS reform. He refused to run on tax reform. He rejected a commitment on indexation of the tax scales. He pledged to repeal Labor’s modest income tax cut, thereby running as the higher tax leader. He refused any significant assault on Labor’s IR laws. He made only modest bottom-line budget savings with a higher deficit over the first two years. For most of the term he had no policy on the energy transition, nuclear aside (a flawed agenda for the distant future). Defence spending was a big policy difference only announced after voting began. Aside from a few comments about “welcome to country” he ignored culture issues the entire time. This agenda was constructed only to maximise votes – where it failed. It revealed a lack of confidence in Dutton’s ability to persuade and sell an ambitious Coalition agenda. It exposed an absence of conviction within the Liberal Party. There was no values-based coherence and, along with Dutton’s unpopularity, it exposed the failure to define the Liberal Party brand for the Australian people.

After this, recovery will be a hard road. There is a psychological reluctance in the community about the Liberals. It will require a big effort to resurrect the party’s values. But will the Liberals even agree on those values?

The Liberals will need to avoid repeating their main blunder from the 2022-25 term: thinking that public disenchantment with the Albanese government will translate naturally into support for the Coalition. It won’t. But don’t think the public will stand and applaud the expanded Albanese government. Again, that won’t happen. Many people might be shocked by the scale of Albanese’s triumph. History suggests Australians typically respond to big electoral wins by growing more critical of the winning side.

Albanese will aspire to change the nation. In today’s world of mounting challenges he will need a government of muscular direction and policy toughness – but the Australian public is not there. Its focus is economic security, regulatory guarantees, social assurance, energy cost relief and more government paternalism. The political mood and the policy needs are in conflict.