Morrison, Xi the odd couple of the climate war

Despite being stuck in the most dysfunctional relationship in 50 years, observers fear Australia will become China’s ‘accidental ally’ at Glasgow.

Neither would like to admit it, but Xi Jinping and Scott Morrison have a bit in common right now. They have formed a rhetorical odd couple, as they push back against the Atlantic consensus that dominates the international climate debate.

“The actions of Australia speak louder than the words of others. There’ll be lots of words in Glasgow, but I’ll be able to point to the actions of Australia and the achievements of Australia,” Scott Morrison said this week.

Knowingly or not, Australia’s Prime Minister was using a Xi-ism.

“Action speaks louder than words,” China’s supreme leader told UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres in May.

“The Chinese always keep their words and do what they say,” he said as pressure began building on the world’s biggest current polluter.

At times in recent months, as the Glasgow COP26 climate summit has approached, it has sounded as if Morrison and Xi were sharing a speechwriter.

“We won’t be lectured by others who do not understand Australia,” Morrison bristled this week as he unveiled a plan to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

Xi strikes a similarly defiant pose. “We will not … accept sanctimonious preaching from those who feel they have the right to lecture us,” he thundered in July.

On Hong Kong, Taiwan, Xinjiang and a host of security questions, Australia and China have never been further apart.

Climate change is different. Chinese climate observers have predicted “severe conflicts” at Glasgow.

Australia and China could be on the same side of many of those upcoming conference biffos, despite being stuck in the most dysfunctional period in their more than 50-year old diplomatic relationship.

Xi’s top climate advisers clearly signalled this week that nobody should expect China to bring forward its net-zero target from 2060.

“Instead of dazzling attendants with new ‘targets’, China would rather focus on how to realise current goals,” a member of the Chinese delegation to the COP26, who requested anonymity, told the Global Times, the tub-thumping Communist Party-controlled tabloid.

The Global Times, which sits under the oversight of Xi’s propaganda machine, added this kicker: “The anonymous delegation member said that the entire world is tired of empty promises made on the climate issue. He urged countries, especially Western countries, to meet their funding goals first before pointing fingers at other countries.”

Australia is one of those arriving with a new target.

It is a win for US President Joe Biden – although one the Morrison government, especially its junior Coalition partner, is defensive about.

Some onlookers worry Australia could be an accidental ally of China’s at Glasgow.

“While there are some similarities between the Chinese and Australian interests, the differences are bigger than the similarities,” says Professor Ross Garnaut, the eminent economist, former Australian ambassador to China and author of a seminal climate change review for the Rudd government.

“The big difference is that Australia has a huge interest in the success of America. China doesn’t necessarily share that interest,” Garnaut tells Inquirer.

More than a bit rich

Australia, at least in its posture, remains an outlier among rich countries on climate change policy.

Its status as the world’s fourth-largest energy exporter gives it a different worldview from most of its peers in the OECD, a group of wealthy countries.

But much of Morrison government’s climate policy – with a focus on technological change – is aligned with the world’s most populous countries.

Investment in new technologies to reduce carbon emissions is not a fudge for China, India or Indonesia, which have a combined three billion people, or two-fifths of the world’s population.

All three have power networks that rely overwhelmingly on coal power. Huge investment in new renewable energy technologies is the only way that is going to change.

The rich world agreed to help fund that enormous change in the developing world at the Copenhagen summit back in 2009. It still hasn’t met its $US100bn commitment, even as it wrangles some of the world’s poorest countries to up their climate ambition. It is more than a bit rich, as Xi’s advisers will be saying all fortnight in Glasgow.

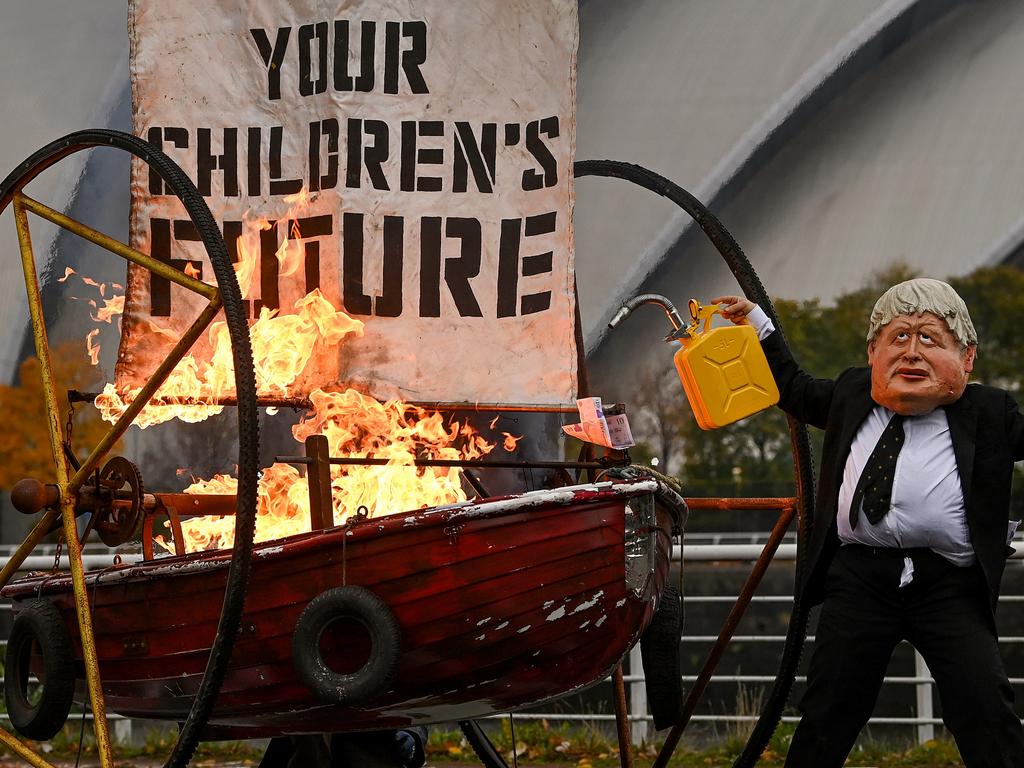

So imagine the debrief in Jakarta’s Presidential Palace after the call this week from British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who after welcoming Indonesia’s commitment to the 2060 net-zero target, asked them to “bring the target forward to 2050”.

Indonesia’s President, Joko Widodo – who is known as President Jokowi and unlike Xi will be at Glasgow in person – says it is “impossible” for his country to do more to address climate change without the help of rich countries.

“It’s impossible if we don’t get funding help. If we don’t have the technology, it’s also difficult,” he said on a recent trip to Borneo.

Indonesia wants to invest in renewable projects to capitalise on its potential in hydropower, geothermal, wind, solar and marine current, but that requires billions of dollars of funding.

For most of Indonesia’s 270 million people, the environmental crisis is not about international politics or what promises the President takes to Scotland, but what their central and local governments are doing to clean up their polluted air and water.

For them, the pressing issues are those that blight their own health and that of their children.

They worry about the haze that hangs over their gridlocked roads, the toxic run-off from factories, the plumes that billow from power stations and the acrid smoke that blankets their own homes from the annual land-clearing fires.

Jakarta is routinely ranked among the most polluted major cities in the world. Its poor air quality is estimated to cause 5.5 million cases of disease each year.

Istu Prayogi is one of 32 plaintiffs who won a class action last month against the Indonesian and Jakarta governments over the city’s air pollution.

The 56-year-old lecturer at the Nusantara Jaya Tourism Academy says he has suffered for years from what he had previously assumed was a chronic flu before a succession of doctors made the link between the non-smoker’s clouded lungs and headaches and the city’s poor air quality.

The case dragged on for two years before an Indonesian court found President Jokowi, Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan and several other government ministers guilty of environmental negligence, and ordered them to address the problem.

Prayogi says he “felt relieved” when the judges made their decision, though is sceptical Indonesian politicians will sincerely address the problem.

“The sources of pollution are the industries and factories, and the government gives them permission,” he told Inquirer.

“From what I hear from my friends in the field, the main source is from coal-fired power plants, and also transport and the people who burn waste.”

Prayogi says he knows little about the Glasgow conference but hopes it will bring some relief.

“Even to feed our families, we have to struggle. Do we have to struggle for something as basic as clean air as well?”

Which system is better?

India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, will also be at Glasgow in person. Modi has not signed up to a net-zero target – in 2060, 2050 or any other time. His government says India needs “carbon space” to raise hundreds of millions out of poverty.

And, like Indonesia’s President, his main focus at the summit is on securing more support from the rich world.

Garnaut says India’s request for international support is a good one.

“Everything we can do to encourage that is in our economic as well as strategic interest,” he says.

Like Indonesia, India insists the burden for climate change action rests disproportionately on the shoulders of developed countries that have grown rich over decades burning huge amounts of fossil fuels. China continues to argue that it is in that same disadvantaged club.

It is a tactic that is nearing the end of its lifespan, according to Garnaut.

“I think China will have to achieve zero emissions by 2050 like the developed countries,” he says, noting its rising wealth. “And I think that China has the technological and economic capacity to do that.”

Beijing is being coy about its plan to get there.

Last weekend, the Chinese Communist Party’s most senior 200-odd figures circulated a “working guidance” on how its economy – currently the source of 28 per cent of the world’s new carbon emissions – will achieve net zero by 2060.

It runs to 21 pages in its official English translation. Like the Australian government’s 129-page plan, which was released this week, it contains no economic modelling.

Labor called the Morrison government’s effort less a plan than a “vibe”. That seems a fair description of what China released

Which does not mean Beijing won’t pull it off.

The hardmen who run the world’s highest-polluting economy say they are clear about where they are going. They see a new economic model and they want to dominate it.

By 2060 – if not before – the Chinese Communist Party says it will have “fully established a green, low-carbon and circular economy and a clean, low-carbon, safe and efficient energy system”.

“China will be carbon neutral, and it will have achieved fruitful results in ecological civilisation and reached a new level of harmony between humanity and nature,” says their plan.

That economic nirvana will require an energy revolution to transform China from its coal-dependent present, where electricity is currently being rationed.

Will it happen? China’s citizens hope so.

“Beijing’s air is much better than a few years ago,” says Xu Daqing, 58, during a walk in the east of China’s capital.

But a wave of pollution earlier this week in Beijing and 35 other cities in northern China was an unpleasant reminder that cleaner air is a work in progress in the world’s second biggest economy.

Li Shuo, a Beijing-based climate and energy policy officer at Greenpeace East Asia, channels the confidence of many in China’s policymaking circles when looking at the decades ahead.

He notes the Biden administration has been unable to clear its enormous climate package through its gridlocked congress before Glasgow.

The shock of then president Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement of America – the world’s biggest historical carbon polluter – still reverberates.

And Trump, or someone sharing his Trumpy-worldview, could return in 2024.

“If you think about US politics, I think they won’t make too much progress in 10 years’ time,” Shuo tells Inquirer. “Essentially, like it or not, this is a question of which system is better.”

The stakes could not be higher for the President of the superpower China wants to supersede.

The same goes for Biden’s allies.

additional reporting: Chandni Vasandani

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout