In August 1997, a tsunami of grief swept Britain at the news Diana, Princess of Wales, had died in a car crash in a Paris road tunnel.

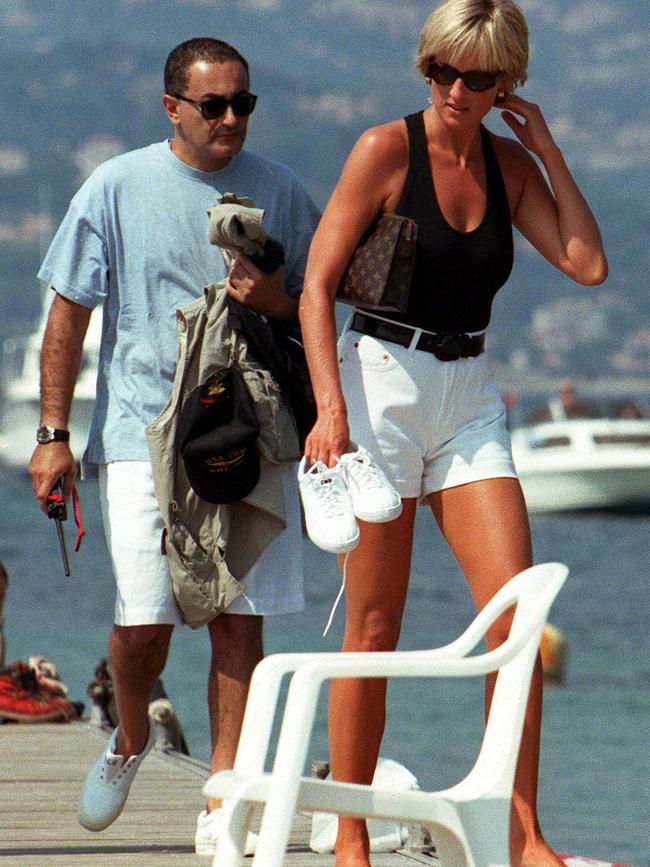

To most people, the death of her lover, Dodi Fayed, in the same ghastly accident was almost a side note to the tragedy of Diana’s death in a car driven at speed by a drunk chauffeur, chased by paparazzi through the Parisian night.

But for one man the deaths of the lovers were far more than a tragic story; their demise also had killed off his last, best chance of achieving his greatest dream – becoming British.

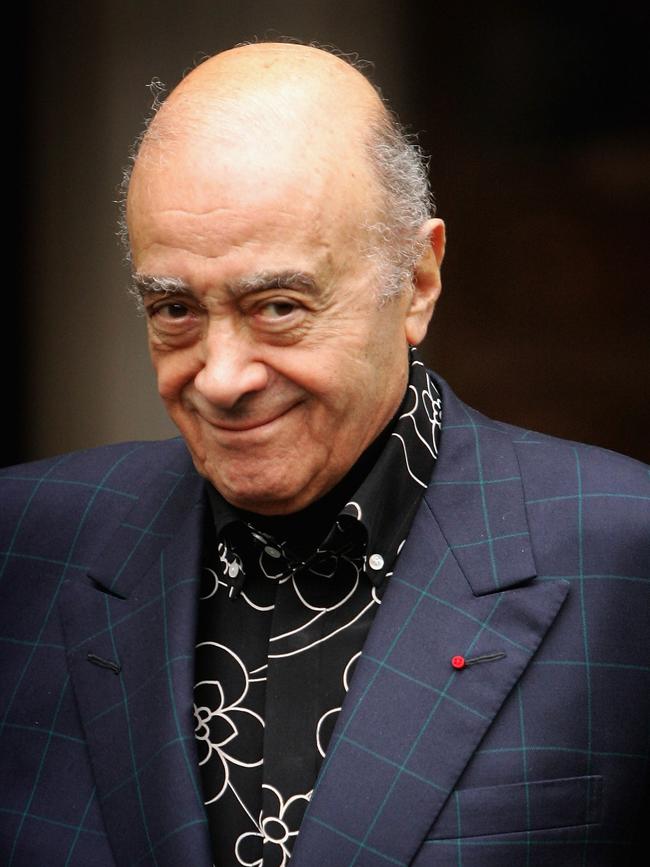

By the late 1990s Mohamed al-Fayed, the ambitious Egyptian son of (depending on who you talked to) a shipping magnate or a poor schoolteacher, had established his position at the top of Britain’s business world – via not entirely sanitary means. (In an investigation into his affairs the British Department of Trade and Industry would condemn him as a “liar” who was “guilty of deception on a grand scale”.)

But despite al-Fayed’s financial success, his decades-long battle to be accepted by British society so far had been fought in vain.

He had bought the landmark Harrods department store in Knightsbridge, the Paris Ritz hotel and had taken a 50-year lease on the duke and duchess of Windsor’s house in Paris, so keen was he to embed himself into the highest of high society. He’d even added the prefix al to his surname in an attempt to appear more aristocratic – and therefore acceptable.

In Arabic, al means “the house of”, just as the prefixes de in French and von in German also denote aristocracy. His fakery led to satirical magazine Private Eye dubbing him “the phoney pharaoh”.

But despite his huge wealth, despite the fact his ownership of Harrods brought him into royal circles – rubbing shoulders with Queen Elizabeth and Princess Diana, with whom he became friendly – English society as a whole continued to snub its collective nose at him.

Worse, he twice was refused a British passport after failing the Home Office’s “good character” test, in the main because of a “cash for questions” scandal in the late 1980s in which he paid two Conservative MPs £2000 each to ask questions of behalf of Harrods.

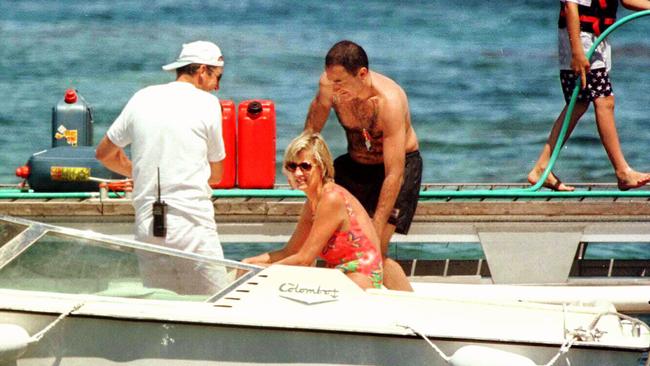

So when he invited Diana and her sons William and Harry to holiday with his family, including Dodi, on his yacht in the south of France and a romance blossomed between the pair, al-Fayed was sure they would marry and, finally, society would open its gilded gates to him.

How could it not? He was about to become father-in-law to Diana, the mother of the future king. He couldn’t be ignored now.

Bereft of his son and his dream when Diana and Dodi died in that Parisian tunnel, he claimed the couple was engaged already and Diana was pregnant. He went on to falsely accuse the royal family – namely Prince Philip and Prince Charles – of ordering the couple’s deaths, horrified that a member of their family might marry a Muslim.

Today, however, the question on many people’s lips is: what if Diana had lived and married Dodi – and a sexual predator of such monstrous proportions had become part of the royal family? What then? Would we be asking how much Diana knew? Or if the royals were part of a cover-up?

In truth, even before Diana and Dodi had met, the rumours had begun to bubble of al-Fayed’s abusive behaviour to the young women on Harrods’ staff. Far from the roguish but harmless old man portrayed on the hit television series The Crown, al-Fayed had been harassing and sexually abusing young women for years – as early as 1987, according to an explosive BBC documentary aired this week.

In the late 1980s and ’90s al-Fayed’s behaviour was an open secret in London: the owner of the country’s most British, most proper department store was a monster, as one of his victims has described him, who preyed on girls as young as 15 in his insatiable and depraved quest for sex.

Young women who worked on his staff – both his personal secretaries and the girls on the retail floors of Harrods – were warned never to be alone with him and, if they found themselves on their own in his presence, to keep their distance. It was a warning with which many of them found it impossible to comply. Like Harvey Weinstein, Jimmy Savile and Jeffrey Epstein, al-Fayed used his position of power to force his victims, literally, into submission.

We now hear tales of how he threatened some girls with sacking if they didn’t accept his sexual advances, groped others despite their pleas to leave them alone, and raped those who wouldn’t comply with his demands.

According to the BBC, one victim was told by Harrods staff the boss knew where her family lived.

Another girl, allegedly raped in al-Fayed’s St Tropez apartment, offered up tapes and transcripts of his abuse only to watch in despair as lawyers shredded them in front of a senior HR official.

In 1995 – when by now he was friendly with Diana but a year before she met Dodi – al-Fayed’s behaviour was finally made public, in a Vanity Fair article alleging racism, staff surveillance and sexual misconduct by the Harrods boss, who was then aged 66.

Al-Fayed sued, leading to a two-year investigation by Vanity Fair’s then UK editor Henry Porter, who gathered so much information of al-Fayed’s abuse that a judge told him: “You would win this case if you proved only 75 per cent of what you already have.”

Porter also found evidence that al-Fayed was surveilling his staff and Porter became concerned for Diana as her relationship with Dodi developed.

“It was vital that she understood that all al-Fayed’s properties were wired for audio and video, and that she could never be sure of having a private conversation on his premises, let alone being able to undress without being watched,” Porter wrote in an article in The Observer last weekend, adding that he never knew if his warnings – passed to Diana’s good friend Rosa Monckton and her husband Dominic Lawson – ever got to the princess.

Had the case aired in court, Diana might have been made aware of the vile reality of the man with whose family she was becoming entwined. But even as al-Fayed and his team moved to settle the case, Dodi and Diana were killed and Conde Nast – publisher of Vanity Fair – closed the case “out of respect for the grieving father”. But the accusations would only continue – as would al-Fayed’s furious denials. In December 1997, a number of Harrods’ staff told ITV’s The Big Story how al-Fayed would grope and kiss them against their will, stuff cash in their bras and demand sex. He angrily denied their stories and the claims again evaporated.

The following year, 1998, journalist Tom Bower published Fayed: The Unauthorised Biography, which once more aired claims of sexual assault of Harrods’ staff at the hands of their employer.

Once more, al-Fayed denied the allegations, with his official spokesman, Michael Cole, calling them “a travesty of the truth” and accusing Bower of betraying their trust in him.

In the wake of the BBC documentary, Bower wrote in The Sunday Times: “For decades, all this was known. And yet Britain’s libel laws and a supine establishment allowed the criminal to escape justice. Exposing him now should shame those who knew the truth during his lifetime.”

Bower was right. For years the claims continued but were shut down in every case as al-Fayed put his powerful team of lawyers and publicists on to the claimants and the judiciary turned a blind eye.

A few allegations made it as far as the police: one of the victims – a 15-year-old named in the BBC documentary as “Ellie”, reported an assault in 2008.

The claims went nowhere and Britain’s Crown Prosecution Service has now admitted that not only did its prosecutors conclude there was insufficient evidence to charge al-Fayed in that case, it also knocked back a rape allegation by another victim in 2015.

In 2013 a young woman in her 20s accused al-Fayed of rape but again no charges were brought. In 2017 and 2018 more women came forward, some waiving their right to anonymity in their search for justice against al-Fayed. Again, he walked away untouched.

We now know that even more women were being abused; 20 women spoke to the BBC for its documentary Al Fayed: Predator at Harrods and since it was aired nearly 200 more have come forward, some with horrific stories of abuse, many describing how they were forced out of Harrods and made to sign non-disclosure agreements when they stood up to their boss or he tired of them.

Some of the victims are now taking action against Harrods, which al-Fayed sold in 2010.

Dean Armstrong KC, who represents many of the victims, described the Egyptian billionaire as “a monster enabled by a system that pervaded” the Knightsbridge store.

Bruce Drummond, a barrister working with Armstrong, said: “This is the worst case of corporate sexual exploitation of young women that … probably the world has ever seen.”

After ruining the lives of scores, if not hundreds of women, and escaping justice all the way, al-Fayed died peacefully at home in August last year, surrounded by his family.

In obituaries, his treatment of women was mentioned in passing, if at all, and usually described only in the context of a humiliation for his second wife, Finnish socialite Heini Wathen Fayed.

More Coverage

Anne Barrowclough is a senior digital journalist for The Australian. She spent most of her career as a journalist on Fleet St, primarily for the London Times, where she was a feature writer, Features Editor and News Editor. Before joining the Australian, she was South-East Asia editor for The Times, covering major events in the region including both natural and political tsunamis and earthquakes.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout