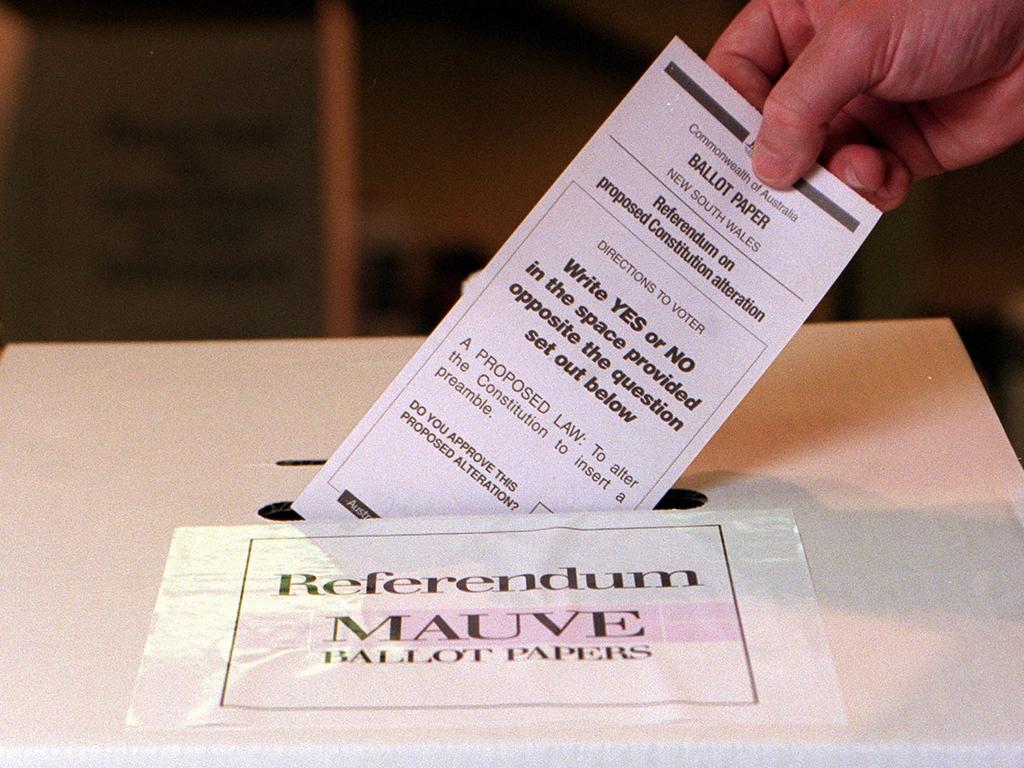

Moderate chief justice Stephen Gageler to preside over interpretation of a successful voice amendment

His appointment is particularly significant for two reasons. It shows the approach of the Albanese government to the most senior judicial appointments. Even more important, Gageler will preside over the interpretation of the Indigenous voice amendment to the Constitution should the referendum pass.

Gageler was the obvious pick in the same sense that Sam Kerr is the natural captain of the Matildas. He is clever, constitutionally moderate and personable. It would have been impossible to go past him, except that some truly bizarre choices have been made by other governments.

Gageler is acceptable to both sides of constitutional politics. For example, he accepts the existence of implied rights in the Constitution – contentiously invented by previous High Court justices – but has shown no particular enthusiasm for extending them.

Even more significantly in the current poisonous constitutional climate, he was one of three minority judges in the Love case who rejected the proposition that Indigenous Australians could never fall within the aliens power of the Australian parliament. His position was clearly correct but was courageous in terms of legal politics and won applause from the constitutional conservatives.

He is not strictly what would be called a black-letter lawyer, but he is not adventurous. He maintains that judges do make law – which is true – but is very cautious about context and extent. He may well develop the common law but will respect the Constitution.

He does have a sense of humour. For years, we were two corners of an abstruse triangle with another constitutional lawyer, each arguing about the number of types of inconsistency between federal and state laws. The argument ended when Gageler admitted (and I conceded) that we had forgotten what our own positions were.

What all this tells us is that the Albanese government, contrary to some expectations, is not going to play games with High Court appointments. It will not appoint a Transylvanian from Tasmania who identifies as a platypus. On the contrary, it seems to prefer clever, moderate, demonstrably appointable candidates. Thank God and Sir Owen Dixon.

This preference also shows in the appointment of Justice Robert Beech-Jones to Gageler’s former spot as an ordinary High Court judge. From the Supreme Court of NSW, Beech-Jones is a highly respected lawyer with no whiff of exoticism. As a common law and criminal expert, he will balance Gageler’s public law experience.

All this will be immensely important if the referendum on an Indigenous voice does succeed. A radical court might make hay. If Gageler has anything to do with it, he will make sure the grass grows but will mow it to the right height.

This must come as an enormous disappointment to the No case. For months, a mainstay of its argument has been that the High Court will run amok in its interpretation of the constitutional words around the text. Now, instead of a judicial Caligula, they have got a mainstream judge whose hobbies include accompanying his Catholic wife to weekly mass.

We can expect a great deal of trawling into Gageler’s constitutional past by nay-sayers over the next few weeks. There will be breathless denunciations of his professional affection for activist chief justice Sir Anthony Mason, and any oblique tolerance of broad constitutional implications.

But his judicial record speaks for itself. Gageler’s temperament as a judge is moderate, measured and restrained. If he believes a “conservative” approach is appropriate, as in the Love decision, he will follow it, but as a matter of law rather than personal preference.

The main issue for the Gageler court around the voice will be interpreting the power of parliament to regulate the exercise of its powers. The No case has maintained a frenzy around the potential for the High Court to undermine parliament, based on a melange of wild speculation, selective quotation and the fears of unidentified constitutional lawyers afraid to publicly express their opinion.

The fundamental question is the extent to which parliament can legislate to “control” the voice. Clearly, it cannot contradict the constitutional text, so that the voice cannot “make representations on matters relating to Aboriginal people”. But what latitude is left?

The general words of the amendment give parliament the power to make laws on “matters relating” to the voice. There were people who wanted stronger words, including me. But saying an elephant is stronger than a rhinoceros is not saying rhinos are 10-pound weaklings.

On the face of it, the words are strong. As Gageler knows better than most, it is a constitutional principle that powers of the federal parliament should be interpreted broadly. This is a legal fact, rather than the clueless constitutional riffing of senior No campaigners such as Nyunggai Warren Mundine and Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price.

Another thing embedded in Gageler’s legal mind, but apparently missed by the No campaign, is that constitutional provisions are to be interpreted as a whole, not cut and diced for media opportunities. The proposed amendment does not just give parliament power to make laws about the voice. It gives specific capacity to make laws about its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

Every one of these envelopes enables parliament to make laws firmly locating the voice within proper constitutional and political limits. For example, are you worried the voice might go off on frolics of its own, preferring UN conventions to infant mortality? The bluntest route would be to forbid this under parliament’s general power to make laws about the voice or its specific right to define its powers.

But if concerned this might contradict the basic constitutional text, simply make a law compelling the voice to give priority to practical improvements rather than international frolics. Then fill up the agenda with a sufficient number of real problems that the voice will never have the time or inclination to go on a fact-finding trip to Geneva.

Worried the voice will be an exclusive clan of excessively remunerated, over-budgeted bureaucrats? Make laws requiring strong qualifications for members, forcing membership to be turned over at regular intervals, mandating modest remuneration, setting overall budget limits, confining staff numbers and banning business-class flights.

Worried about endless, expensive inquiries that could go anywhere, without focus and evidence? Make laws imposing reporting times and parameters for inquiries, mandating that they be based on documented evidence, and making the whole operation subject to the normal assurance measures for government action: the auditor-general, Freedom of Information, administrative review and the criticism of the person who makes the tea.

How would any of these laws not be about the powers, procedures or functions of the voice? Do tell, Warren and Senator Price.

But the point is neither Mundine nor Price gets to give us the authoritative answer. That will come from a High Court led by Gageler, who will apply the law, not fantasy. The court will give parliament the full extent of its power, but no more. It will give proper constitutional respect to the voice, but nothing extra.

This is real adherence to the Constitution, not peddling constitutional zombies.

Emeritus professor Greg Craven is a constitutional lawyer and former vice-chancellor of the Australian Catholic University.

The appointment of Justice Stephen Gageler as chief justice of the High Court was a lot like Christmas. Everyone knew it was coming and just about everyone was looking forward to it.