Mind the gap: where Australia is exposed to nuclear attack

As the chances of a US-Russia conflict increase, it’s foolish to think our geographic distance will safeguard us. Our ‘American spy base’ remains the priority target.

The risk of nuclear war is now “higher than at any time since the Cold War”, according to the former director of Australia’s Joint Intelligence Organisation, emeritus professor Paul Dibb. In his paper The Geopolitical Implications of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine, published this week by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Dibb warns Australians not to believe that our geographic distance from a European war will safeguard us from nuclear attack.

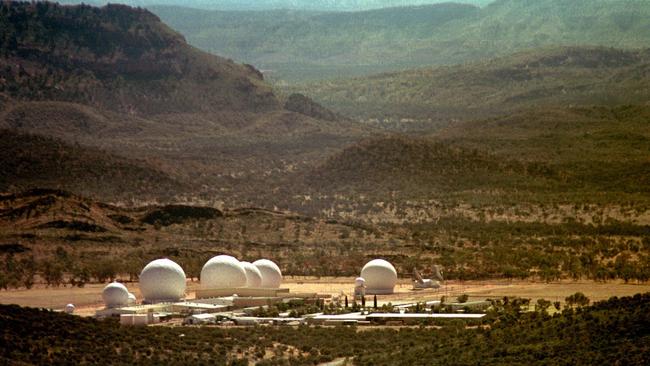

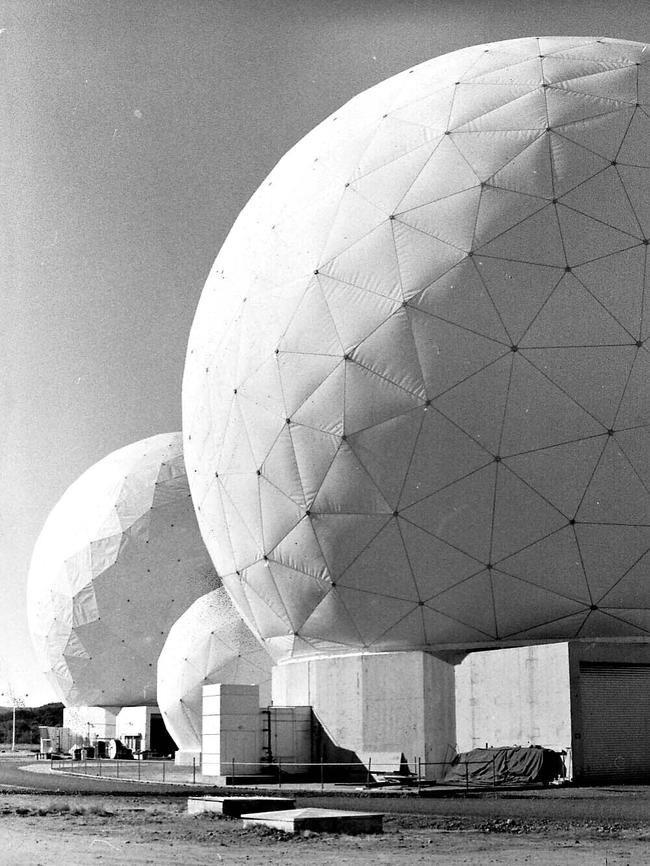

The priority target is what the Russians still call the “American spy base” at Pine Gap in the Northern Territory. “We need to plan on the basis that Pine Gap continues to be a nuclear target,” Dibb writes, “and not only for Russia. If China attacks Taiwan, Pine Gap is likely to be heavily involved. We need to remember that Pine Gap is a fundamentally important element in US war-fighting and deterrence of conflict.”

Dibb goes on to say that Australians “need to understand what the implications would be for Alice Springs, which is a town of 32,000 people only 18km from the base”. What he does not say is that those “implications” have already been examined in a highly classified government study that was covered up for more than 30 years.

The study, by the Office of National Assessments, was ordered by prime minister Malcolm Fraser. Eleven copies were delivered to the undersecretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet on March 30, 1981. Entitled “A preliminary appraisal of the effects on Australia of a nuclear war” and classified “TOP SECRET AUSTEO” (Australian eyes only), it argued that “US facilities in Australia might be targeted relatively early in a strategic nuclear war”.

In fact, statements made by Soviet military commanders indicated that attacks against both Pine Gap and the joint US/Australian base at Nurrungar in South Australia were a near certainty. In “Annex A” of the ONA study, the authors quoted a passage from Marshal Vasily Sokolovsky’s 1968 book Military Strategy, described as “one of the basic documents of Soviet Military doctrine”.

“The logic of war,” Sokolovsky wrote, “is such that if a war is unleashed by the aggressive circles of the United States, it will immediately be transferred to the territory of the United States of America. Those countries on whose territory are located military bases of the United States, NATO and other military blocs, as well as those countries which create these military bases for aggressive purposes, would also be subject to shattering attacks in such a war. A nuclear war would spread instantly over the entire globe.”

The ONA study anticipated that an attack on Pine Gap would take the form of an “air burst … perhaps involving detonation of about a one megaton warhead (about 75 times the yield of the Hiroshima bomb] at an altitude of about 1000m to 1500m … An explosion at this altitude would maximise the area of blast damage on the ground, and hence minimise the effect of targeting inaccuracy”.

The study’s authors believed that Alice Springs would be far enough from the blast not to suffer major damage except for “broken windows … flying glass and other debris, and isolated fires”. Casualties would be “strongly dependent” on the effectiveness of civil defence measures but “there could be some fatalities”.

The ONA study was not the only one to explore the possibility of an Australian armageddon. The parliamentary Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs and Defence conducted its own investigation into potential nuclear threats. Its Sub-Committee on Defence Matters met 45 times, taking nearly 2000 pages of public evidence together with a significant amount of “in camera” testimony. Its report, entitled Threats to Australia’s Security – Their Nature and Probability, was tabled in parliament in November 1981.

Finding out what went on at Pine Gap was not easy, even for the Australian parliament, and the joint committee relied on defence expert Des Ball for information it could not get from the government.

Ball explained that the function of Pine Gap went far beyond the cover story of “arms control”; it played a crucial role, he said, in locating Soviet missiles and radar systems and “allowing more accurate targeting in the development of American nuclear war-fighting capabilities”.

Ball’s evidence convinced the joint committee that “it would be prudent” for Australian strategic planners to assume that in the event of a nuclear conflict between the two superpowers, Pine Gap would be a target. Australians, particularly those living in Alice Springs, would hardly have been reassured by the committee’s assumption that the Soviets would not waste one of their multi-warhead SS18 ICBMs on a “soft” target such as Pine Gap but would to use the older, less destructive and “relatively inaccurate” SS11 missiles.

Drawing on a seven-page government booklet published in 1964 called Survival from Nuclear Attack: Protective measures against radiation from fallout, the committee suggested that casualties could be “drastically reduced” if “non-essential” staff at Pine Gap were evacuated during the prelude to nuclear war. It “would not be necessary” to evacuate Alice Springs, whose inhabitants could protect themselves by such means as “whitewashing and taping windows, installing shutters, cleaning up combustible material and constructing simple shelters”.

Not everyone shared the committee’s confidence that the people of Alice Springs would escape serious harm. In 1985, the Medical Association for the Prevention of War (NT) and Scientists against Nuclear Arms (NT) published a booklet entitled What Will Happen to Alice if the Bomb Goes Off? Written by a local doctor, Peter Tait, it identified phenomena that had been underplayed or ignored in the ONA study. Tait warned, for example, that anyone within 80km who was looking towards Pine Gap at the moment of the explosion risked being blinded; Alice Springs is less than 20km away.

Neither the joint committee’s report nor the ONA paper explored what the intense heat of a nuclear explosion over Pine Gap might do to nearby suburbs of Alice Springs, despite the fact that thousands had been incinerated by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki blasts.

According to Tait, “everything flammable within 10km of Pine Gap would catch fire. This includes the White Gum Estate, parts of the airport road and Stuart Highway, a section of Larapinta Drive, the Rangers’ Station at Simpsons Gap and all scrub and animal life … people in the open west of the South Road would receive third-degree burns”.

The joint committee, the ONA and Tait all assumed that a Soviet nuclear attack on Pine Gap would consist of a one-megaton air burst above the base. If, however, the Soviets opted for a ground burst, the population of Alice Springs would be hit with lethal levels of radiation carried by dirt picked up by the explosion. The ONA study stated that if the wind direction were within about 45 degrees of Alice Springs, “most people not evacuated within one hour would receive fatal radiation doses”.

Wind patterns in central Australia made such an outcome unlikely, but if it were to happen Tait predicted that the inhabitants of Alice Springs “would die of radiation poisoning within 24 hours” and “tracts of central Australia would become uninhabitable”.

Fraser shared the ONA paper with a handful of ministers, who discussed it at a meeting of the cabinet’s Foreign Affairs and Defence Committee. The bureaucracy, however, was determined to keep the ONA study secret. The head of the ONA, Bob Furlonger, asked for all copies to be returned to his office “for destruction”.

A cabinet document entitled “Certificate of destruction of classified matter” records that 14 copies were destroyed in front of a witness and that Copy No.2 was “sent to ONA for their records”. Like the ONA paper itself, the certificate confirming its destruction was classified “TOP SECRET AUSTEO”. Another copy, No.5, described as being “retained on a cabinet file for record purposes”, eventually wound up in the National Archives and was released in 2013, heavily redacted, under the Freedom of Information Act.

The authors of the 1981 ONA study sated that “constraints on nuclear war between the superpowers” made such an attack “unlikely”. In 2022, Dibb is not so sure. Europe’s security order, he argues, is being “fundamentally challenged”, with a real risk of war between Russia and the US. “The ugliest days of this war are in front of us,” Dibb warns, “not behind us.”

Tom Gilling is the author of the 2019 book Project Rainfall: The Secret History of Pine Gap, published by Allen & Unwin.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout