Bernard Salt: Different destiny as Millennials make their mark

The closing decade heralds a new one replete with villains and heroes bleating about betrayal, sacrifice and how they were “done wrong”.

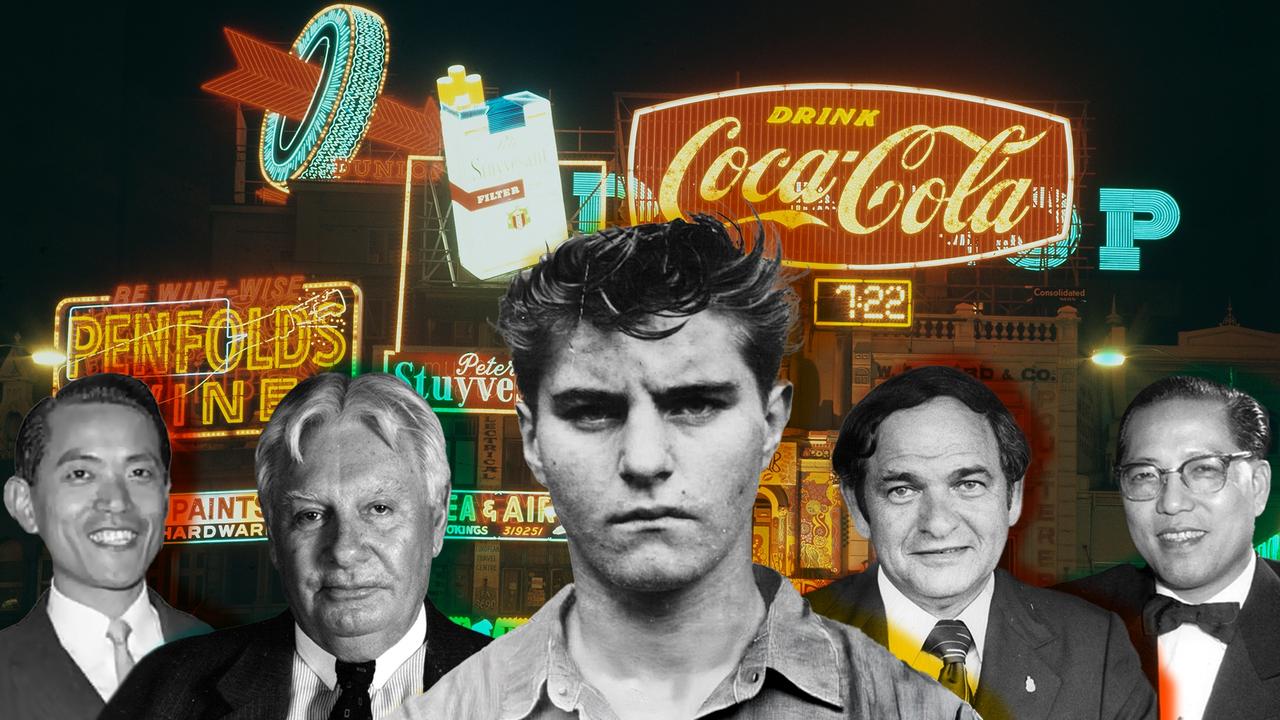

The 2000s will be tagged forever as the decade bookended by terror and crisis, namely the 9/11 terror attack and the Wall Street-inspired global financial crisis. The 1990s, on the other hand, was the decade of recession and recovery. The 80s in Australia at least was the reform decade courtesy of the bold visioning of the Hawke-Keating government.

So, how will the 2010s be tagged?

I see the 2010s as a transformative decade where we changed course. Australia is a bit like a supertanker: the course we were on in 2010 is different to the course we’re now taking. As a consequence, our destiny is different.

In a decade, I think we will look back and see the 2010s as having been pivotal in delivering a better, smarter, more productive and perhaps even a safer Australia. Not because of a single event or calamity but because of myriad smaller corrections that we have put into place to collectively change who we are and where we’re going.

The 2010s was a decade where the demographic composition of the Australian people both transformed and expanded. This unique perspective is best viewed via the chart, which shows net growth in the population by single year of age in the decade to 2009 as compared with the decade to 2019. In the 2000s we added roughly three million residents; in the 2010s we increased this figure to around four million. (In the 2020s we will again add four million.)

The transformation that took place during the 2010s involved the rise of the Millennials (born 1984-2002) from late teenagers and early 20-somethings to early 30-somethings, and the moving on of the baby boomers (born 1946-64) from late 50-somethings to late 60-somethings. This has been an important decade for managing a number of generational issues that also have surfaced as tensions.

It didn’t matter in the 2000s when boomers progressed from 40 to 50 or in the 90s when they aged from 30 to 40 because they were still in the workforce, still paying tax, and still doing whatever was required at each stage of the life cycle. But the ageing of the boomers matters in the 2010s when they transitioned out of the workforce and into retirement or, as they like to call it, into the lifestyle stage of the life cycle. All of a sudden there’s a skills shortage that needs to be plugged by importing more skilled immigrants as well as students who then enter the workforce.

Between the 2011 and 2016 censuses, overseas-born workers accounted for two-thirds of net job growth in Sydney and Melbourne. For Canberra this ratio was nine out of 10 jobs going to overseas-born workers.

The first baby boomer ever invented (born July 1946) just nine months after the demobilisation of the World War II troops turned 65 in 2011, and across the following eight years all their younger mates (born 1947-54) have thus far also tripped across the “retirement line”.

But there’s at least another decade (and more) of bulging boomers in their late 50s and early 60s just counting down the days until they too can retire, go on a cruise and claim whatever benefits and entitlements may be on offer. If you accept that there was a baby boom in the 50s then there must be a baby bust from the 2010s onwards.

This decade, “our” decade, has been little more than the opening gambit to a bigger movement; it was an overture to a more dramatic opera that will play out in the 2020s, replete with villains and heroes singing soulful arias about betrayal and sacrifice and how they were “done wrong”.

This baby bust starts with a skills exodus from the workforce, then it proceeds into a my-time-now frenzy of spending and lifestyling and Rhine River cruising (see the advertisements in this paper) and then it will move into what will be a deeply reflective — in fact, quite spiritual — stage as boomers contemplate their own inevitable mortality. The final stage, a dramatic exodus via the great abyss, awaits the vast majority of baby boomers, lurking in the shadows and crevices of the 2030s.

“Our” overture baby-bust decade has lifted immigration levels, raised concerns about integration and social cohesion, and transformed our universities and workplaces. Accordingly, concepts such as diversity and inclusion have seeped into the soul of institutions across Australia in this decade.

Given the baby-boom baby-bust inevitability of Australia’s demography, to have remained “on course” would have delivered a lesser workforce and a nation without the requisite skills or the immigrant-driven ambition to create the kind of wealth and prosperity to which we think we are all entitled.

The transformation of the millennial generation from disengaged and largely mute teenagers into galvanised, purpose-driven, widely travelled, digitally connected, highly vocal 30-somethings has shaped this decade.

Their (global) response to my satirical comments about smashed avocado in The Australian in October 2016 coincided with the start of what some see as a noble intergenerational battle.

The cost of housing and the fairness of franking credits are just two of the skirmishes that have played out thus far. There’ll be more in the 2020s.

Millennials will say: “You boomers should have provisioned better for retirement in your time, not ours … this is an issue of intergenerational fairness.”

Boomers will respond: “But we’ve paid taxes all our working lives … we’re entitled to enjoy the fruits of our labour including a drawdown on taxes paid.”

And sitting quietly in the corner, minding their own business as the two generational behemoths battle it out, are the Generation Xers (born 1965-83) and the post-Millennials — there’s still debate over their name — born between 2003 and 2021.

The Xers’ ascension to positions of corporate and political power took effect during the 2010s (for example, Qantas’ Geoff Dixon to Alan Joyce and the prime ministerial shift from Malcolm Turnbull to Scott Morrison). Generally, the Xers have just got on with it, perhaps because this quiet generation never could get a word in with all those bossy boomers buzzing about.

The post-Millennials, on the other hand, have burst on to the landscape as a second echo (that is, grandchildren) of the baby boomers. (You know, it must really annoy other generations that all generational definition takes a reference point from the boomers. The baby boomers are a bit like Greenwich Mean Time: Xers follow boomers; Millennials are the children of the boomers; post-Millennials are boomer grandchildren.)

The 2010s saw a surge in the post-millennial primary-school-kid population, for which I credit Peter Costello who, as treasurer in 2004, implored Australians to “have one for the country”. Dutifully, and I must say, enthusiastically, the Australian people responded (see chart).

The ramping up of immigration, the transformation of the workforce to knowledge work, the surge in Sydney and Melbourne’s rate of growth, the spending splurge on infrastructure, the skyrocketing of house prices, the internationalising of parts of our cities, the sniping between old and young — all have their roots in our nation’s underlying demographic change. But then no decade is without its challenges.

We are not at war. There has been no recession. We are not racked by internal conflict that spills on to our streets. We can and we do raise taxes and dole out the benefits in a series projects and programs designed to improve our way of life. (In other countries corruption and conflict siphon off this life-improving source of spending.)

For our scale, I say we are the most successful, cosmopolitan, and prosperous nation on earth, delivering an unparalleled lifestyle for many. Sure we have our problems and there’ll be plenty more in the decade ahead. But there’s no place I’d rather face those problems than right here in Australia.

Bernard Salt is managing director of The Demographics Group. bernard@tdgp.com.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout