Melbourne must be content to watch AFL grand final from afar

There are far worse fates than watching a game of footy on television. But this grand final in particular is an event for which the MCG might well have been designed.

Ten days ago, a sponsored truck with a refrigerated container backed up a ramp at the Melbourne Cricket Ground to take receipt of a three square metre roll of turf from its long-dormant goal square for a 1700km journey north.

Its ostensible purpose was to sow a little of the AFL grand final’s traditional home in its temporary home, the Gabba, in Brisbane. Its underlying purpose was to get the sponsor’s name on the side of the trailer in the photographs.

Corporate grabs for pieces of the footy action are common this time of year in Melbourne, but this one fell even flatter than usual — a reinforcement of, rather than a remedy for, how far Australian football feels from the state that has loved it longest and deepest.

An AFL grand final in Brisbane? Why not a Boxing Day Test on Ash Wednesday or a Melbourne Cup in Sydney?

It was, on Daniel Andrews’s say-so, still a public holiday in Melbourne on Friday. To do what exactly? To hold your own masked grand final parade in the driveway? To prepare not to attend the Cox Plate?

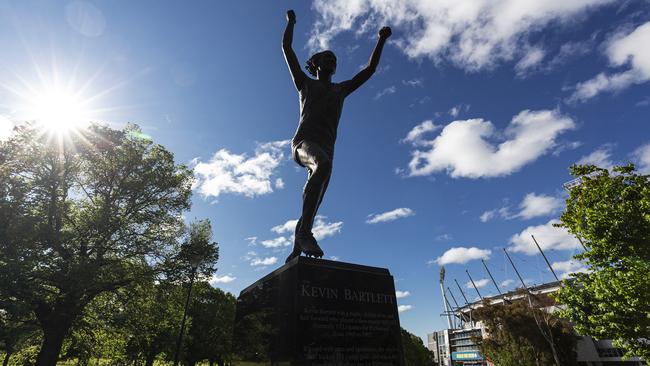

Richmond v Geelong today is the first all-Victorian grand final since 2011 — an event for which the MCG might well have been designed.

Yet COVID consciousness precludes not just attendance for all save a fortunate or forward-thinking few, but even gathering in homes and pubs where the vast majority usually partake of it.

There are, to be sure, far worse fates than watching a game of footy on television. And it would, perhaps, have felt stranger still had the grand final been any different to the rest of the season, consumed overwhelmingly in two dimensions rather than three.

Yet who even six months ago would have thought a Victorian winter possible without football? Who’d have imagined a whole season of such passivity and vicariousness, connected to the game like a patient on an intravenous drip?

Not even the pleasure of a local game on a suburban oval, or a scrum of eager children gathering for Auskick; at best maybe kick-to-kick on a median strip or, in my case, crossing the Jack Worrall Bridge near Princes Park on my daily walk.

This grand final marks half a century since an immortal Carlton v Collingwood grand final which, as Martin Flanagan describes vividly in his book 1970 (1999), is often deemed to be “when the modern game was born, the progenitor of the one we see today where no positions are fixed and the field of play is one large fluid mass”.

It incorporates the legends of Ron Barassi’s inspiration (“To win without risk is to triumph without glory”), Alex Jesaulenko’s screamer (“Jesaulenko, you beauty!”), Ted Hopkins’s crowded hour of glorious footy life. Just as importantly it also set an all-time attendance record of 121,696 — about 5 per cent of Melbourne’s then population.

Because the MCG’s capacity has since been shaved a little, this totemic figure is likely to stand in perpetuity. But it’s that ongoing habit of huge crowds that as much as anything undergirds Victorian pride in football.

It’s ritualistic to go to the footy; it’s also, subtly, patriotic. Others watch; we attend; we even mingle; to be in a crowd mixing the fans of rival clubs is a better introduction to civics than the most erudite lecture about bicameralism and the separation of powers.

This goes back a ways. The great colonial chronicler Richard Twopeny, who acclimatised to Australia after emigrating by becoming a footballer, was among the first to note the thrall that their homegrown game exerted on Melburnians.

“I feel bound to say that the Victoria game is by far the most scientific, the most amusing to both players and onlookers, and altogether the best,” he wrote in Town Life in Australia (1883).

Football, he noted, attracted “10 times the crowds as Sydney sport”, the majority watching “its every turn with the same intentness which characterises the boys at Lord’s during the Eton and Harrow match”. A game was “a sight for the world”.

On returning to his home city after a decade’s idyll on Hydra, author George Johnston was transfixed by the sight of the MCG for the 1965 grand final between Essendon and St Kilda, watched by 104,846.

In The Australians (1966), Johnston describes “that unbelievable roar of over 100,000 screaming zealots baying for blood and bruises, the toss and tumult of partisan colours, the streamers, the hats, the emblems, banners, frenzy, hysteria …. So, for a time, men become gods and heroes.”

Hyperbole? Sure: the event invites it. The very name “grand final” is an expression with a touch of brio, a remnant of colonial big-noting. Most sports get by with mere finals. Ours is grand, a theatrical melding of final with grand finale.

It’s certainly preferable to the dismal American borrowing of “the big dance”, not to mention the new hipster vogue for calling the Brownlow Medal “the Charlie”.

More Melburnians, of course, do not go to the football than do; but that is a choice. Having no choice to exercise, having no means of expressing affinity, experiencing only singly a pleasure that is best felt communally: this has been lockdown chagrin.

With all its technical expertise and analytical proficiency, television is a distorting glass. The camera tagging the ball accentuates the ground as thoroughfare, not the ground as space.

It is hard even to decide whether to sympathise with the players or to envy them. Sequestered as they have been since July, they have also been free to do what they do best.

They look fit; they wear tropical tans; engaging post-match with socially distant interviewers, they sound content.

Hubs may have alleviated as many problems as they have posed, conferring on clubs otherwise unobtainable degrees of control over potentially vagrant players. A couple of quarantine breaches aside, there have been no off-field scandals to speak of this season, perhaps also because journalists have been kept at safe distance.

The grand final involves clubs that have become good advertisements for hub life.

Richmond have won 12 of 15 games since transplantation, boosted by Bachar Houli’s return from paternity leave.

Geelong were able to offer compassionate leave for more than half the season to Gary Ablett, whose son is gravely ill.

Premiers two of the last three years, the Tigers polled ninth among clubs in the Brownlow, indicative of their evenness and consistency, and won an epic, attritional preliminary final against Port Adelaide.

Shorter games may have suited the Cats’ older list. At the end of their preliminary final victory against the Lions, the team converged excitedly on their supernumerary squad members near the fence, grateful for their contribution to constructive preparation.

The prospect of the contest is enhanced by the personalities.

Richmond is personified by Dustin Martin, simultaneously the era’s most sheerly explosive player and most reticent personality, his mohawk and tattoos less an advertisement than a disguise.

Nobody has polled more votes in a Brownlow than Martin did in 2017. On the night in question, he took a teammate as his date. When he won, he declined to kiss the medal, as cliche demanded, and unfolded a speech someone else had written for him. Yet his image could be used alongside the dictionary definition of contested possession.

For Geelong, attention will fall on the contrasting pair of Ablett and Patrick Dangerfield.

Ablett’s 357th game is set to be his last. He is 36, although his gleaming cranium and baby face have rendered him strangely ageless. No AFL footballer, it is attested, has hand passed the ball more; none, surely, has foiled so many tackles.

Dangerfield is the footballer as head prefect, socks always up, hair immaculately parted, face a mask. Others beamed and bantered after last week’s game; he was as inscrutable as ever, perhaps already war gaming his first grand final.

For all the frustrations of watching from afar, television does present the opportunity for instant intimate analysis, and there were moments last week which conveyed much of each player.

In the first quarter, Ablett seemed to be swallowed up in a pack like Laocoon; then, somehow, he delivered by hand to Dangerfield. The naked eye hinted at a throw, a view that had to be revised when a replay showed the left fist in unexpected proximity to the ball.

In the third quarter Dangerfield, in falling with his arm pinned, managed to hand off to Ablett, a goal resulting. This time the replay revealed that the unsighted umpire had missed a throw.

Ablett’s quicksilver impulses; Dangerfield’s encyclopaedic shrewdness: today is the last time we shall see them in combination.

But we won’t, not in Victoria, be seeing them ourselves, enlivening them with our own imaginations, joining others in a swelling cheer.

The only prospect is a mediated, curated, commercial spectacle from a frankly rather dowdy ground in a distant city amid an abnormality so prolonged it has grown routine. And the MCG turf? After its long cold journey, the tatty mat was unrolled and laid outside the Gabba boundary line. You couldn’t get more symbolic than that.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout