Meet the Hendra Club of doctors tackling the deadly virus

Vet Peter Reid had never seen anything ike in all his time as an equine vet — until now.

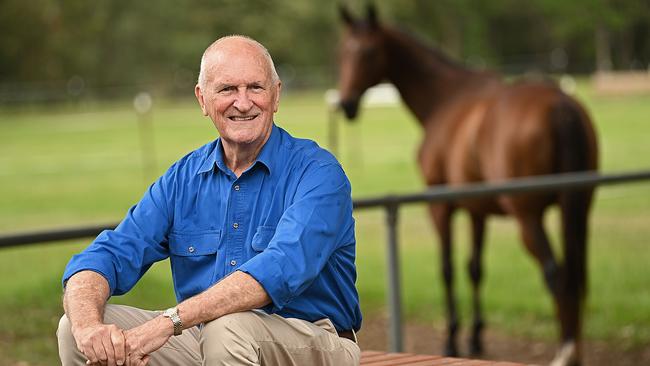

Peter Reid was there when the virus first reared its fearsome head in 1994 and the remarkable thing is he’s still going, tracking and second-guessing it all these years later as a founding member of the Hendra Club.

You wouldn’t call it a labour of love when the emotions in play are fear and dread. More an obligation to understand and act on what happened after a mare named Drama Series fell sick at the Brisbane stables of Brisbane racehorse trainer Vic Rail, setting a grim benchmark for the dozens of outbreaks that would follow.

Reid, now 73, had never seen the like in all his time as an equine vet. He can still recall almost to the minute the horrifying sequence of events. Rail’s fiancee, Lisa Symons, also a partner at the stables in Hendra, a pocket of tin-and-timber homes between Doomben and Eagle Farm racetracks, rang him on September 8, 1994, about the horse. She was carrying her head, not eating. Could he drop by?

Diagnosing an infection, Reid administered antibiotics and a course of anti-inflammatories. By 4 o’clock next morning, Symons was back on the phone: Drama Series had collapsed after having a turn in the stall. A strapper, Ray Unwin, had tried to restrain her, to no avail. The mare and her unborn foal were dead when Reid arrived.

Two Tuesdays later, on the 20th, a frantic Symons reached out again. “We’ve got a dozen sick horses,” she told him. Rail was so ill she was going to take him to hospital, while Unwin was off work with what they thought was flu. Things started to move at a dizzying pace.

Within 12 hours, seven horses had died or been put down, while another sent to a spelling property was dead. The trainer next door also had a horse down, semiparalysed by convulsions. Reid was at a loss to explain what was going on.

A pathologist from the University of Queensland suggested African horse sickness, but that didn’t make any sense. The disease had never been reported in Australia and it was supposed to be spread by midges, which were yet to make an appearance in the early spring.

Poisoning? Maybe. Rail was a “colourful character”, as they say in the racing world, and somebody might be acting out a grudge. Or else the feed could have been tainted. But how to account for the horse he had to put out of its misery at the neighbouring stables? Or the one that had now died in Kenilworth? “I just thought, ‘holy mackerel, something really serious is going on here’,” Reid remembers. He was right about that.

The 9/11 legacy

It would take weeks, but eventually scientists at the then Australian Animal Health Laboratory in Geelong identified the previously unknown Hendra virus, slotting in the first piece of a jigsaw that Reid continues to assemble.

Like the emergent coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 — which we now know all too much about thanks to COVID-19 — it is zoonotic, meaning it jumps from animals to people. This makes these pathogens especially dangerous. The otherwise formidable human immune system can be turned to putty by an attacker it doesn’t recognise. Four of the seven Australians known to have contracted Hendra virus died, starting with poor Rail, who never stood a chance. Reid attended three of the funerals.

That’s not the only reason this is very personal business for him. Another two of the victims were fellow vets, one of whom, Ben Cunneen, infected in the winter of 2008 while treating an ailing horse in the Brisbane bayside suburb of Redlands, was a good friend. Reid has come to know the survivors, including Unwin and young mother Natalie Boehm, the veterinarian nurse who was struck down alongside Cunneen, as well as the families of the other victims. “This has become a big part of my life,” he tells Inquirer.

Bit by bit researchers filled in more of the gaps. Fruit bats were found to be the live natural reservoir for the virus, starting the chain of infection that led to people. Their excreta — most likely urine — then infected the intermediate or amplifying host, the horse. Laboratory tests showed that all manner of animals — dogs, cats, ferrets, chimps — could catch Hendra, yet only horses passed it on to humans. Why? Scientists suspect it has something to do with horse physiology but there is still no definitive explanation.

The good news was that the disease was relatively hard to catch. Hendra was not airborne and a person needed to be significantly exposed to contaminated bodily fluids to get it. Hence the risk to vets and allied personnel. But all that changed when the closely related Nipah virus was discovered in Asia.

This too is transmitted by bats and if you have seen the 2011 movie Contagion, you know the rest: a slaughtered pig infects one person, then another, and another … as was the case with the first known Nipah outbreak in southern Malaysia and Singapore in 1998-99, though thankfully in real life the outbreak was contained.

Chillingly, a subcontinental variant, Nipah Bangladesh, was found to spread readily from person to person. In some instances, the fatality rate was upward of 80 per cent, deadlier than Ebola and far more infectious to boot.

At the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland, a young US Defence Department scientist named Chris Broder decided this worrying new genus of viruses comprising Hendra-Nipah, Henipavirus, warranted a closer look. The lines of international concern were converging.

CSIRO researchers at the super-secure AAHL labs in Geelong — known today as the Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness — had made Hendra a priority, combining study of the virus with world-leading work on bat populations under Linfa Wang. But it would take the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the US in 2001 to bring the Hendra Club together. In the hushed aftermath of that carnage, both Hendra virus and Nipah were classified as potential bioterrorism agents by US authorities and Broder finally secured the funding he had been chasing.

He approached Wang and senior colleague Bryan Eaton with a proposal: why not work together? The Americans had the cash, crackerjack facilities and expertise in vaccine and therapeutics development, while AAHL had years of experience with Hendra. “If it wasn’t for 9/11 it would never have happened,” says Broder, now 59, reflecting on the progress.

The opening tranche of US government funding, issued by the National Institutes of Health, came through in 2003, worth $US2.025m over five years. Broder was able to funnel $US260,000 a year to Geelong, a godsend for the research program in Australia, which had stalled. The money would continue to flow until 2015, with the annual instalment to AAHL increasing to $US440,000.

The death of Reid’s friend and colleague Cunneen, just 33, in 2008 was followed by that of fellow vet Alister Rodgers, in Rockhampton in August the following year. (The case of the other known victim, Mackay sugarcane farmer Mark Preston, was not linked to Hendra virus until after his death in October 1995. His wife, also a vet, had approached Reid a few months earlier and they realised he had had contact with suspect horses in August 1994.)

Cracking the code

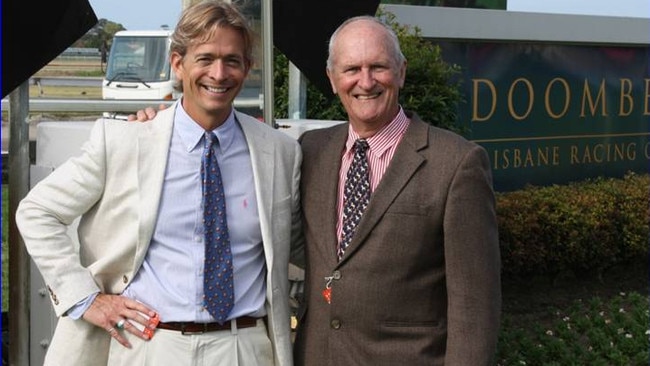

If the Hendra Club had an inaugural meeting it was on the Sunshine Coast, north of Brisbane, in October 2009. Reid, Wang and a jet-lagged Broder, on his first visit to Australia, caught up at a scientific conference at the Twin Waters resort. Reid was adamant about what was needed to protect people: a vaccine.

“We’ve got one,” Broder said.

In Bethesda, he and co-researcher Katharine Bossart had picked apart the Hendra genome and identified a key glycoprotein on the crust of the virus critical to it establishing infection. When synthesised, it became the basis of a simple but highly effective prototype vaccine that neutralised not only Hendra but also Nipah in laboratory studies. “All it is is a protein … the native structure of the G-protein,” Broder says. “It’s not an unusual vector, it’s not RNA, it’s a basic vaccine platform that’s extremely safe and effective.”

It also provided the basis of a monoclonal antibody therapy for people. By 2010, Bossart had joined the CSIRO team in Geelong. She was on leave in California when Sunshine Coast horse owner Rebecca Day and her 12-year-old daughter, Mollie, were heavily exposed while nursing a sick mount. Doctors warned they had a 25 per cent chance of getting Hendra. Broder flew a batch of serum to Bossart and, using her own frequent-flyer points, she climbed on a flight to Brisbane where doctors administered the experimental treatment. They couldn’t say whether it worked, but neither mother nor daughter became ill. “You wouldn’t read about this,” Reid marvels.

Pfizer released its Equivac HeV horse immuniser, developed with the CSIRO in Australia in 2012, paving the way for Broder’s group in Bethesda to step up work on the human vaccine. This went into phase-1 clinical trials in the US state of Ohio last year before the coronavirus pandemic forced a halt to the program. Broder says the safety study is expected to resume soon. Generously, he gifted the cell line for the antibody therapy to Queensland Health, allowing 14 people exposed to infected horses to be dosed to date. If Nipah ever breaks out in earnest, the candidate vaccine could be fast-tracked as a lifeline to our near neighbours — and Australia’s forward defence.

“This vaccine has been used in more animals models showing complete protection against Hendra and Nipah than in any other emerging virus vaccine,” he says.

The next threat

The Hendra Club, meanwhile, has moved on to fresh challenges — Reid partnering with a new generation of virologists to create the Horses as Sentinels project, a tripwire against future outbreaks. Thankfully, there have been no human casualties since Rodgers’ death almost 12 years ago; the last major eruption was in 2011 when 24 horses died across 18 infection sites in Queensland and northern NSW, though isolated cases continue to emerge. The most recent, outside Murwillumbah, NSW, killed a horse last June.

Broder’s thinking has turned to what lies between Nipah virus at the raw edge of a pandemic threat in southern Asia and Hendra here. “We know there are other viruses out there in between them because we are seeing the antibody reaction in different bat species,” he says. “It’s not Hendra as we know it, it’s not Nipah and it’s not Cedar (another henipavirus isolated in Queensland in 2009). So what is it? We don’t know but we need to find out.”

The Horses as Sentinels team, including equine vet turned scientific sleuth Ed Annand, whose PhD work at the University of Sydney anchors the project, gun molecular sequencer John-Sebastian Eden, 35, of Westmead Institute for Medical Research, and veteran CSIRO scientist Ina Smith, announced this week it had identified a new and as-yet-unnamed strain of Hendra as the cause of an unexplained horse death outside Brisbane in 2015.

The finding is important, not only because it confirms Broder’s suspicions about the existence of Hendra variants. The belated hit on the horse sample turned out to be 99 per cent genetic match with a virus sequenced from a grey-headed flying fox in Adelaide in 2013 and, less emphatically, with fruit bats in other states.

This cast in doubt one of the few certainties about Hendra virus in Australia: that it was primarily carried by black and spectacled flying foxes whose range in Queensland and northern NSW delineated the hotzone.

Authorities in Victoria and South Australia might need to recast their advice that the risk in those states was minimal, Reid cautions. “Hendra virus was always thought to be a Queensland-northern NSW disease because it’s where the outbreaks have occurred since 1994,” he says. “People elsewhere may have thought it was not a risk in their area because they only get grey-headed flying foxes. They really need to reassess their protocols, the way they manage risks in their horses, and consider their options.”

Looking back, he is amazed how far the scientists have come since his jarring introduction to the virus three decades ago. “It’s an amazing group,” Reid says of the Hendra Club. “We have got complete trust in each other’s observations and work, and the way we share information.

“That is what is really unique about it. We don’t have any issues with scientific jealousy which can occur with some discoveries. We have got an attitude: this is deadly serious.”