Media’s role in Brittany Higgins saga has escaped scrutiny for too long

The media’s role in the Brittany Higgins imbroglio has escaped scrutiny for too long.

There is no one-size-fits-all model for journalism. Journalists will court a source and maintain that relationship in their own way. Looking inside a story is a little like watching a sausage being made. Not always pretty. There is much preparation, even mess.

This applies even more so in the case of investigative reporting which, almost by definition, involves persuading someone to say things they are reluctant to share.

It often requires great powers of persuasion to convince a source they and their story are in safe hands, and to do so may require a degree of cajoling, or of feigned intimacy. There is also, often, a great deal of genuine care and compassion shown by a journalist to a person who is telling a story that is deeply personal and difficult.

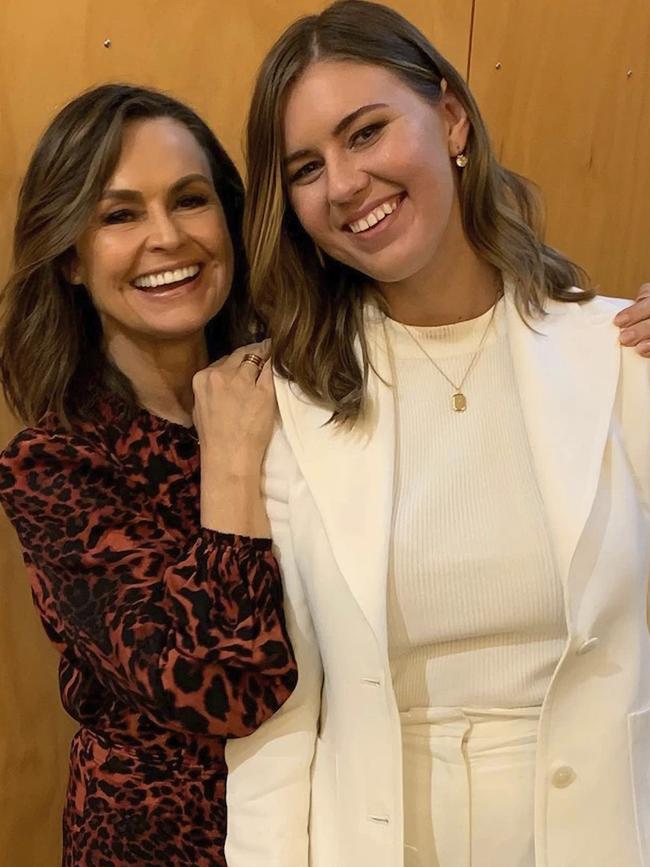

On February 15, 2021, journalists Samantha Maiden and Lisa Wilkinson broke the story of political staffer Brittany Higgins’s alleged late-night rape in March 2019 in the office of her boss, defence industry minister Linda Reynolds. It was the first day of a sitting week in Canberra. That week, and for months to come, many of our elected representatives in the nation’s parliament casually tossed aside the presumption of innocence.

At the end of that week, Maiden thanked Higgins: “Just having played my little part in your operation has been one of the greatest moments in journalism I’ve ever had. So, thank you,” she texted.

The “operation”, as Maiden called it, raised concerns from those early days that the combined media and political frenzy was undermining justice. This, after all, was an extremely serious allegation. Bruce Lehrmann – the fellow staffer accused by Higgins – was entitled to due process, a fair trial and the presumption of innocence, principles that underpin the rule of law in a healthy democracy. Lehrmann has always maintained his innocence.

He was not named in Maiden’s or Wilkinson’s report. Wilkinson’s story is now the subject of defamation proceedings brought by Lehrmann, who says he was identifiable in the Ten story.

Higgins aired her allegations in the media before she progressed a formal rape complaint with police. Texts revealed by this masthead between Higgins and her then boyfriend, now fiance, David Sharaz, show another part of their strategy was to seek Labor’s help to prosecute her claims in the political arena.

Higgins and Sharaz sought out favoured journalists to amplify the political angles. They picked Wilkinson and Maiden.

Once Higgins decided on media and politics first, and formal police complaint second, the behaviour of the media – along with the behaviour of politicians, the police and the ACT Director of Public Prosecutions – inevitably would come under scrutiny in this national political scandal.

Higgins’s strategy led to a trial by media that enveloped Lehrmann. Because of sub judice rules, had Higgins gone to the police first and Lehrmann been charged, any public reporting would have had to proceed on the assumption he was innocent, making clear there had been no finding of fact against the former staffer. Instead, the only law that might have restricted publication was defamation.

Reynolds, who subsequently was wrongly accused of covering up the alleged rape, has lodged a submission in recent days to the ACT board of inquiry run by Walter Sofronoff KC that there should be a criminal deterrent to stop people airing an alleged criminal offence in the media and in the political forum to advance their own interests. Reynolds has suggested changes to the ACT Crimes Act to reflect NSW provisions that make it an indictable offence for anyone who knows or believes a serious indictable offence has been committed and fails to report it to police.

Though there are exceptions for circumstances where disclosure is not required, they do not let a person off the hook where a complainant wants to first pursue a claim through the media and through parliament.

Higgins responded that this would “silence victims”. In fact, Reynolds’s submission is that the proper operation of the criminal justice system will allow prosecutions to take place free from media frenzies.

There may be room for law reform. There is, most definitely, room for reflection. In a sign of how skewed this story became, the evidence to date suggests the only two people who encouraged Higgins to go to the police when there was an inkling of sexual activity were Reynolds and her former chief of staff, Fiona Brown: the same two people who were pilloried in the media, day in, day out, for not supporting Higgins.

There was, however, plenty of support from others in the media. Inquirer has seen many text messages exchanged between Maiden and Higgins from January 2021 until mid-2022. If these were simply exchanges between two friends, they should remain private. But these are texts between a woman who alleged rape and a political cover-up, and a journalist who chose to tell the story and pursue many angles of the story as told to her by Higgins and others.

On January 22, 2021, three weeks before Maiden published her exclusive story, the journalist texted Higgins suggesting she get legal advice about a potential workplace claim:

“I spoke to the lawyer from Maurice Blackburn. He’s happy to talk to you informally – no charge next week. But only if you want to – I just want to make sure you’ve got some sort of advice about potential employment claim.”

Three weeks later, on February 18, 2021, Maiden texted Higgins again about getting legal advice. Higgins responded: “I’m really cognisant of not wanting to go after anyone for money.” That evening and the following day, in another 10 text messages, Maiden continued to encourage Higgins to speak with an employment lawyer and mentioned ComCare and the Department of Finance.

“I think a specialist employment lawyer who has experience with Comcar [sic] claims and department finance would he [sic] good,” she texted Higgins.

Higgins did put in a claim with the Department of Finance – for $3m – using a lawyer from a different firm.

The claim was uncontested and settled by the commonwealth in December last year. The secret settlement, reported to be about $2m, has generated a great deal of public interest. Reynolds has revealed that she may refer the circumstances around the payment to Higgins to the new National Anti-Corruption Commission.

Testimony given at the Sofronoff inquiry uncovered many examples of how red-hot media coverage affected the workings of the criminal justice system in this case. Australian Federal Police Commander Michael Chew, deputy chief of ACT Police between August 2018 and 2021, told the inquiry that intense media pressure led to him directing his subordinate Detective Superintendent Scott Moller in early August 2021 to charge Lehrmann despite police concerns about lack of evidence.

The AFP acted in haste, presumably under similar media pressure, and wrongly included protected material in the brief of evidence that went to defence lawyers and the ACT DPP. It’s hard to imagine media pressure did not play a part in the DPP going to extraordinary lengths not to disclose certain documents to the defence.

ACT Victims of Crime Commissioner Heidi Yates’s presence with Higgins in front of the cameras raised concerns that a jury would be confused about whether Higgins was a victim or a complainant.

ACT DPP Shane Drumgold’s public statement when he declared there would not be a second trial but said he believed he would have secured a conviction had there been one fed the sense that here was a trial by media. His expression of sympathy for Higgins, with no word about Lehrmann’s right to the presumption of innocence, added to the media circus.

Those who know Maiden say she is a tenacious journalist. A range of her text exchanges with the former Liberal staffer shows a diligent reporter at work: checking details with Higgins, for example as to when she went to the cops in 2019; asking questions, for example of the former staffer’s photo of her bruised leg; seeking quotes from her; discussing other journalists, politicians, staffers, the Women’s March, politics of the day; and so on. Indeed, in March last year I congratulated Maiden on being a great journalist. It was many months before this newspaper revealed a swath of material that shed more light on the saga.

That includes the five-plus hour audio conversation between Wilkinson and Higgins and texts between Maiden and Higgins. In those texts seen by Inquirer, Maiden does not discourage Higgins from speaking to police, nor does she encourage her. Wilkinson’s exchanges with Higgins, recorded by her own producers, include the journalist strategising about how the story could be politically amplified by senior Labor figures. Maiden’s texts with Higgins include nothing like this.

But other text messages from Maiden to Higgins raise questions about whether she got too close to Higgins. And how close is too close?

On March 22, 2021, Four Corners ran Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, a story that featured Maiden speaking about the rape claim. During that program Maiden said this of Higgins: “She’s highly intelligent. She’s very analytical. Uh, she’s very impressive. And she’s very dignified … If you think about what she’s actually achieved, of all the investigations that have been triggered. She put everything on the line, right?”

After the program aired, Maiden texted Higgins:

9:21:06pm Maiden: I hope that was ok

9:21:06pm Maiden: I hope I said the right things

9:21:23pm Maiden: You’re a hero never forget that

Minutes later, Higgins told Maiden she didn’t watch the program.

Jumping forward to August that year, Maiden said “I’m proud of you” and “if you ever need somewhere to stay in Canberra you’re welcome to stay with me”. In late September, Maiden suggested to Higgins that they go on a road trip to Tamworth for the Walkleys award night next year.

Throughout the period Maiden was, of course, covering other stories, apparently without fear or favour, and a story on Wilkinson in October 2021 caused some friction.

In her memoir, It Wasn’t Meant to Be Like This, Wilkinson claimed she left the Nine Network due to the gender pay gap and that she could no longer stay silent and “keep men’s secrets”. Maiden revealed there was more to Wilkinson’s claim about being paid less than her co-host, Karl Stefanovic, than first met the eye: “Multiple sources familiar with the contract negotiations at the time have told news.com.au that while there was a longstanding pay gap between the two hosts, it was the other way around,” she wrote. “They insist that for half a decade it was Stefanovic, not Wilkinson, who was getting far less money than the other co-host.”

A few hours later Higgins tweeted: “Pressing update in the midst of a sitting week from the political reporter of news.com.au.”

That evening Maiden, clearly upset at Higgins attacking her in public, texted her 38 times. When Higgins insisted she was entitled to her own opinion, Maiden responded.

6:22:16pm Maiden: Yes no worries – publicly attacking me though I think given I will always be supportive was unnecessary and sad. I think you probably owed me a ohone [sic] call but so be it.

6:22:35pm Maiden: I will say I will never publicly attack you – ever.

6:22:50pm Maiden: I simply wouldn’t

In mid-November there was another exchange where Maiden appeared upset.

5:15:08pm Maiden: Hey there sorry to be paranoid, but you keep liking tweets where people are having a go at me or something it’s beginning to feel a little strange? Happy to talk if you want to. I’m just Weirded out as you don’t follow me on Twitter.

5:16:29pm Maiden: I’m a bit confused about what’s going on and I feel like I’m in an episode of mean girls or something. And it’s just upsetting that’s all.

5:16:44pm Higgins: Sam, chill. I accidentally liked it scrolling through Twitter. We’re fine.

Was Higgins freezing Maiden out of her “operation”? Perhaps.

Given Higgins’s media strategy, Maiden’s relationship with Higgins is every bit as relevant as that of Wilkinson, whose conduct in this saga has been dissected and critiqued. Wilkinson’s foolish Logies speech led to the trial being delayed. The Sofronoff inquiry revealed a dispute over the DPP’s warning to Wilkinson about her intended Logies speech. Sofronoff may make findings about this.

Regardless, many have asked, not unfairly, whether someone who has worked in the media as long as Wilkinson should have worked out for herself that her words that night could derail a trial.

Wilkinson’s conduct during a five-plus hour chat with Higgins before The Project interview that aired has been scrutinised too, with questions as to whether the Ten Network celebrity showed enough curiosity and whether she coached Higgins. Wilkinson said to Higgins: “I don’t want to put words in your mouth, but if you can enunciate the fact that this place is all about suppression of people’s natural sense of justice.”

On Wednesday, February 9, last year, a sitting week in Canberra, Higgins appeared on stage with Grace Tame at the National Press Club in Canberra. On the Monday, as Maiden and Higgins text about spare seats, and pursuing strong angles that will go into question time, Higgins texted Maiden: “I’m crashing at Laura’s house tonight.”

Laura Tingle became president of the press club in December 2020. If Higgins stayed at Tingle’s house, is this another example of a senior journalist getting too close to an interview subject whose serious allegations of rape have not been tested by a court?

There is a larger question about the level of professionalism at the National Press Club. Did no one on the board of that organisation raise concerns about having Tame, who was a victim of sexual abuse, and Higgins, who had made an allegation with no finding of fact yet made, on stage together? Did anyone consider that the celebration of Higgins alongside Tame might undermine the presumption of innocence for a defendant?

That distinction went over the heads of a room full of senior journalists. Not to mention the scores of female journalists who attended that event. Why didn’t any of them raise this issue in their reporting? Was there some #MeToo spell cast over the many female journalists who wrote about this saga with so little curiosity or care?

Tingle’s texts with Higgins raise concerns about whether their relationship, also, was too close. When Higgins told Tingle about a complaint she planned to lodge about the inclusion of protected material in the brief of evidence sent to defence lawyers, Tingle texted back: “Oh Britt. I’m so sorry. You need this like a hole in the head. How sh.t. How f…ing outrageous.” Tingle texted “lots of Hugs” and signed off with a kiss.

As revealed during the Sofronoff inquiry, the irony is that the febrile media environment caused police to make these mistakes in their rush to pull together the brief of evidence.

Many female journalists attended the March4Justice in early March 2021 where Higgins spoke. It is not unreasonable for journalists to protest against a rotten culture in their workplace – in this case Parliament House. But celebrating Higgins had become a vehicle to do many additional things: advance careers, join the #MeToo juggernaut, indict politicians in general and Scott Morrison in particular.

Behind the scenes, senior male journalists have expressed their concerns to me that the atmosphere at press conferences they attended where these issues were raised had become overwrought and that questions went to women by default as if this had become women’s-only business.

This is not a sign of healthy journalism. It raises the possibility of vigilante journalism by some female journalists who are too invested in an issue to report it fairly by exploring every angle and keeping in mind fundamental principles of our criminal justice system.

The feverishness among some of these journalists matches their hypocrisy. Many journalists and commentators can hardly disguise their squeamishness at new disclosures about the Higgins scandal run by this masthead and elsewhere. There are complaints about privacy and needless political point-scoring, for example aimed at Finance Minister Katy Gallagher and her level of knowledge about the rape allegation before it was made public. The critics were not concerned with privacy and political point-scoring at the start of those scandals.

That’s not how journalism works. No, this is not the time for us to down tools. The media’s role has escaped scrutiny for too long.

In March last year, Maiden texted Higgins: “To the vast majority of Australians – and to me as an outsider your name has been exalted as a hero.” But Maiden was no outsider in this scandal. She assumed a central role once Higgins settled on a strategy of making this a political and media story instead of solely a criminal justice matter. A month earlier, Maiden had won the Gold Walkley for her coverage of the saga.

On June 14 last year, with the trial approaching, Maiden gave Higgins some sage advice: “You’re [sic] only guiding principle is trial. Don’t talk about this in public. Respect the court. Don’t do anything on social media.” Days later, that trial was derailed by Wilkinson’s Logie speech and coverage of it. Maiden knew better than to report what Wilkinson had said that night.

Delaying the hearing in the ACT Supreme Court, Chief Justice Lucy McCallum castigated Wilkinson and other sections of the media where, she said, “the distinction between an allegation and a finding of guilt has been obliterated”.

“I trusted the press,” she said, “and I was wrong.”