Like their friends the Kennedys, Martin Luther King Jr’s family seemed to be foredoomed

Like their friends the Kennedys, the relatives of Martin Luther King Jr seemed to be foredoomed. The Kennedys’ tale is well known; the Kings’ less so.

Martin Luther King Jr would be relieved to know that his family members have long been judged by the content of their character. It was the life's work of his mother and father that the skin colour of Americans be irrelevant.

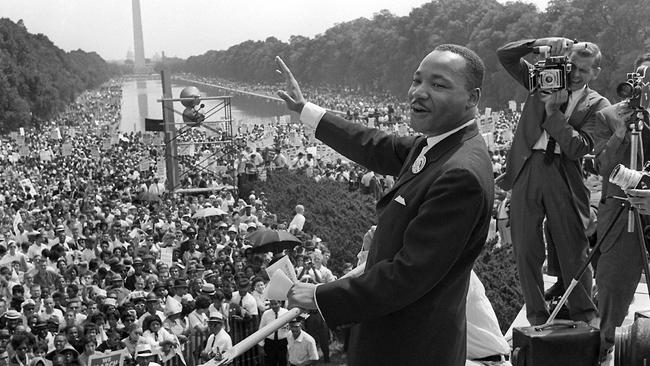

Of course, it is a work in progress, but the US has had a black president who was re-elected for a second term, and, right now, has a black Vice-President – almost unthinkable in August 1963, when King delivered his heroic and often mythologised speech, phrases from which are known by most people.

That speech was written the night before by entertainment lawyer Clarence Jones after a meeting of King and his associates at which their major issues were discussed. Jones’s words weave together the great themes of American life and how the “withering injustice” of slavery and poverty excluded so many from them.

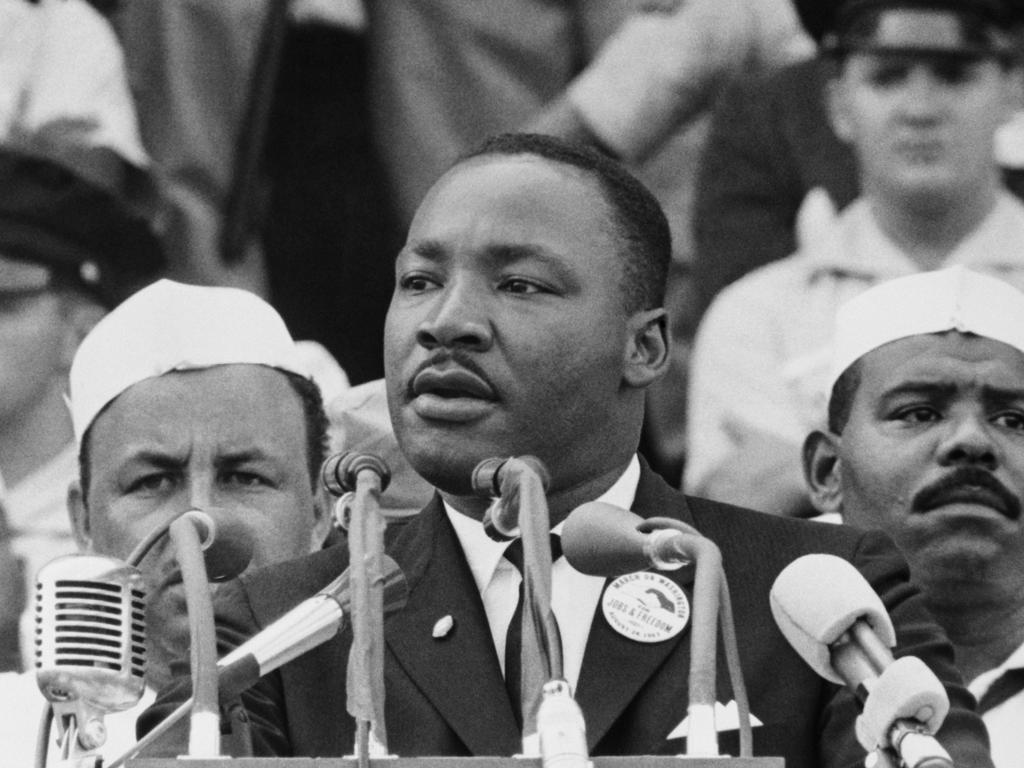

King read Jones’s elegant words deliberately, uttering just 79 of them in the first minute, about half the traditional rate of public speaking. His delivery had an authority none of the actors present – Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Tony Curtis, Charlton Heston, Marlon Brando or Burt Lancaster – could have mastered. He left wide, three-second gaps that hung in slow silence. But during one, an overwhelmed gospel singer Mahalia Jackson shouted out: “Tell ’em about the dream, Martin.”

Jackson and King were old friends. At his request she had just sung the mournful spiritual I Been ‘Buked and I Been Scorned. He later credited her performance for giving him the confidence to sound the piercing clarion call for freedom, the handwritten notes for which he had just removed from his breast pocket.

Jackson was standing nearby and her interjection was heard by very few, but senator Ted Kennedy spoke of it for the rest of his life.

King responded, changing the pace of his words and ad libbed “So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow”, while sliding his notes to the side, continuing with “I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

Kennedy and his brothers, the president John, with not three months to live, and Robert, the attorney-general, who was headed for the White House himself in 1968 and who would be assassinated 53 days after King, shared his dreams.

Both families’ lives turned into nightmares: the Kennedys’ tale is well known; the Kings’ less so. But the fates hunted them just as surely.

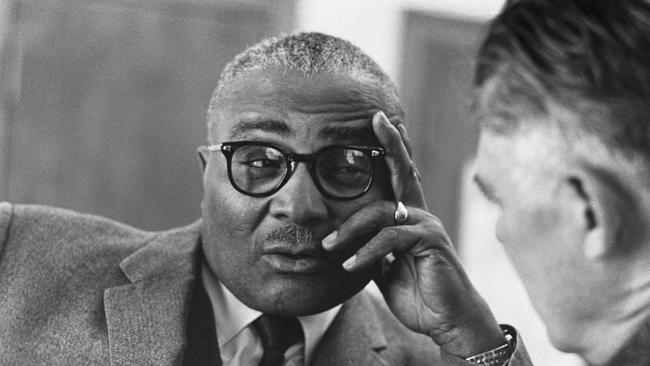

The patriarch of the King family was Martin Luther King Sr, who died 40 years ago this week. He was born in Georgia in 1899, a year that proved the reflexive racism of much of white America but also its capacity for goodwill and understanding. That year a statue was raised in New York to acknowledge the life of escaped slave, abolitionist, social reformer and newspaper editor Frederick Douglass, the most important civil rights figure of the 19th century.

But July 1899 also had seen the lynching of Frank Embree, 19, accused of rape. Before he could stand trial he was kidnapped from authorities and lashed 100 times by a mob that urged him to confess. He did, begged to be killed quickly and was. Many would die like him.

As a boy, Martin Luther King Sr was impressed by the outspoken Baptist preachers who encouraged racial equality. One of them was Adam Daniel Williams, an activist preacher in Atlanta with whom he boarded. Indeed, he became engaged to and married Williams’ daughter Alberta.

After completing his theology education, King Sr also started preaching, and when his father-in-law died in 1931 he took over Williams’ church role, becoming wildly popular and serving as the minister there for more than 40 years.

King Sr had been christened Michael and was known as Mike. He changed his name and that of his five-year-old son Michael to Martin Luther after a European tour in 1935, two years after the elevation of Adolf Hitler to chancellor of Germany. There he came to understand the role of Martin Luther in the rise of the Protestant churches that reformed Christianity. He saw Luther as not unlike the black reformers in America – relentlessly persecuted but ethically and morally right.

King Sr attended the Baptist World Alliance congress in Berlin that ended with a resolution condemning “racial animosity, and every form of oppression or unfair discrimination toward the Jews, toward coloured people, or toward subject races in any part of the world”. But Luther had been an infamous anti-Semite who urged that synagogues, Jewish schools and books be burned. Hitler saw himself as the inheritor of this unfulfilled ambition for which he wrote his own blueprint.

From this distance, the change of name looks odd, but both Martin Luther Kings remained lifetime defenders of Judaism. In any case, King Sr saw something inspiring in Luther’s impassible resistance to authorities, an attitude his famous son would inherit.

King Jr followed his father’s path after being born in his maternal grandfather’s Atlanta home on January 15, 1929. They read from the Bible each day and each night their grandmother would read Bible stories to the children, King’s older sister Christine and eventually a younger brother, Alfred. By then thousands were attending their father’s weekend sermons.

Predictably, King encountered racism, first when the parents of a white boy across the road asked him not to visit. His father explained about slavery and the searing racism of America but instructed his children to rise above it and love every other human being. King saw his father standing up to racism including when they were out together and a policeman called the father “boy”. King Sr said “Martin here’s a boy, but I am a man”.

King Jr attended civil rights marches with the family. The highly intelligent youngster studied English, history and piano. He could recite from memory slabs of the Bible, which greatly expanded his knowledge of the language. But he would become concerned about how literally his father and the Baptist congregation accepted their teachings and questioned the concept of biblical inerrancy.

In 1944 he and some school friends took a train to Washington and were surprised by the freedoms blacks enjoyed there. Buses, cinemas, restaurants, even the churches were not segregated. He saw the future. And it wasn’t the south. This would have to change.

He studied theology at Boston University, during which time he met a New England Conservatory of Music student, Coretta Scott. She thought him a bit short and overeager, and realised that marriage to such a man would be the end of her singing career. But she boarded that bus in 1953 and soon found herself in the middle of America’s civil rights war in which she became a legendary activist and an advocate for change.

In their early years her husband would be stabbed at a 1958 book launch and the family house would be bombed.

The only surprising thing about King’s foreboding words on April 3, 1968, was how long it took him to utter them. The night before he was assassinated he had been feeling ill and sent his best mate, Baptist minister and civil rights activist Ralph Abernathy, to speak for him at the Mason Temple in Memphis, Tennessee. There was quite a crowd and Abernathy could tell they were disappointed. He called King and explained the situation. With foul weather brewing King made his way across town to the church and delivered perhaps the most profound speech of the century.

He said if the Lord had asked him in which era of mankind he might wish to live that he would have sailed past the biblical stories of flood and Exodus, swooped over Mount Olympus and through the Renaissance and eavesdropped on Franklin Roosevelt’s “nothing to fear, but fear itself” address. He would ask the Lord to land him in the second half of the 20th century, a time of unfolding greatness because “when it’s dark enough you can see the stars”.

He urged his audience to march and march again. He had “seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land!”

He returned to the Lorraine Motel, which had been renamed by its black owner in honour of Nat King Cole’s 1940 hit Sweet Lorraine. The singer had stayed there. The Lorraine had always welcomed black artists including Sam Cooke, Otis Redding, Louis Armstrong and Aretha Franklin. Wilson Pickett and Steve Cropper had written In The Midnight Hour in one of its rooms; in another Cropper had written Knock on Wood with Eddie Floyd.

The next day King would be shot dead there by bigoted jail escapee James Earl Ray. Ray fled the scene and months later was arrested at London’s Heathrow airport, where he planned to migrate to what was then the racially segregated Rhodesia.

King associate Jesse Jackson, who had been in the Lorraine carpark, rang Coretta with the news. She had already made history by taking a call from presidential hopeful JFK on the eve of the 1960 election during which he promised to support her husband who had been arrested again.

She fought for her husband’s birthday to be made a national holiday, which president Ronald Reagan signed into law in 1983. She died of ovarian cancer, aged 78, in 2006 and among the 10,000 at her funeral were both presidents George Bush, along with Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter.

In 1974, a young black man, Marcus Wayne Chenault, who had joined a cult called the Black Hebrew Israelites that saw Christian civil rights activists as evil liars, decided to kill Jesse Jackson. He cancelled that trip and instead went to Atlanta to murder King Sr.

On Sunday, June 30 – his 23rd birthday – Chenault was welcomed at the door and into the city’s Ebenezer Baptist Church. He decided it would be easier to shoot King Sr’s wife, Alberta, because she was seated at the church organ playing The Lord’s Prayer. He approached her, shouted “You are serving a false god” and shot her dead using two pistols, also killing a nearby deacon.

Chenault was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. Appeals by the King family, who opposed the death penalty, helped save him. By then, Alberta’s other son, Alfred, was also dead. He too had been at the Lorraine Motel and had to be held back from his dying brother. No one knew how many shooters there were. He also had become a Baptist pastor and was on many a march with and had been arrested alongside his older brother.

While running the campaign for school desegregation in 1963 in Alabama, his home had been bombed. Soon after, when the home of a well-known black lawyer was also bombed, a mob seeking vengeance congregated on the street outside. Alfred stood on a car roof and said that if they needed to kill anyone they should kill him, while urging nonviolence.

Following his brother’s murder, Alfred fell into depression and alcohol addiction. A strong swimmer, he was found dead in his swimming pool on July 21, 1969, the day after man landed on the moon. It was believed the various pressures on him aggravated a congenital heart problem from which family members suffered. Alfred was 38. A daughter, Darlene, died aged 20 while jogging in 1976. His son Alfred died aged 34 also while jogging.

A broken Naomi King, Alfred’s widow, said: “There is no doubt in my mind that the system killed my husband. (He) was murdered.”

Two of King Jr’s children also had short lives: race relations activist Yolanda, his firstborn, died in 2007 aged 51 of an undiagnosed heart problem; son Dexter died this year aged 62 from prostate cancer.

King Jr’s last words in the final speech on the eve of his murder were: “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life – longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will … And so I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout