Majesty and fairytale down to a fine art

The Queen was the most visually chronicled woman on the planet, and she used her mystique to her advantage to project power, duty and awe.

Queen Elizabeth II was one of the most visually scrutinised and recorded people in history, and she shrewdly used that to manage her image over her 70-year reign – even though a handful of artists sought to subvert it.

When Britain’s longest-serving monarch died last week, she left behind a museum’s worth of photographs and painted portraits. London’s National Portrait Gallery catalogues at least 1000 images of the Queen in its collection, nearly all reflecting the way she wanted to be seen as a modern-day royal.

Over the course of her seven-decade reign, a few major artists did try to put their own, edgier spin on her public persona.

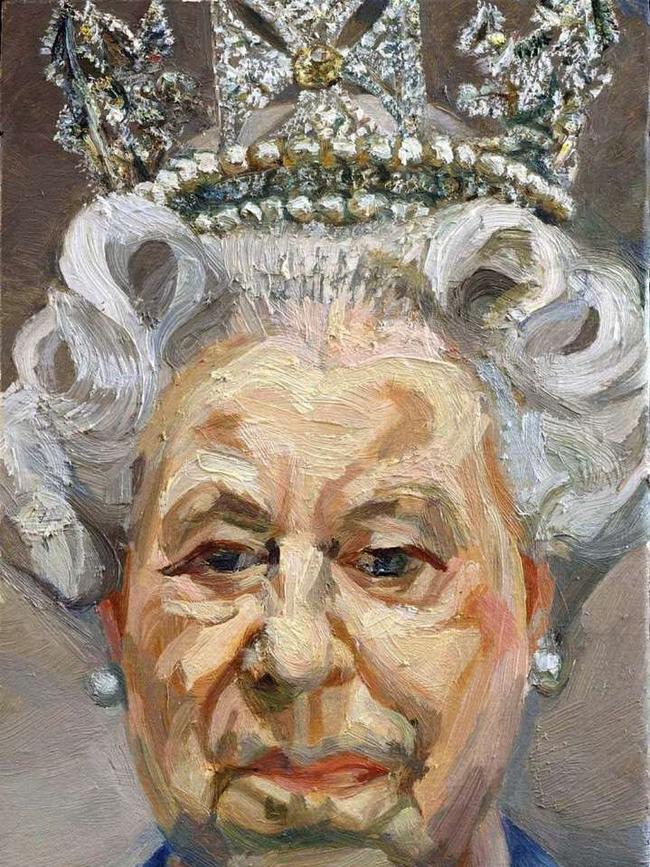

Andy Warhol famously silk-screened her face into a colour-block grid in 1985, adding a version where her face is bluish green. George Condo once painted her with a clown-like visage and bulbous, red nose. Lucian Freud’s candid up-close version of her sparked so much outrage in 2001, The Sun’s royal photographer said the artist “should be locked in the Tower for this”. (He wasn’t.)

In 1977, Jamie Reid and the Sex Pistols even caused a stir by using the Queen’s face as the album cover for the punk band’s provocative hit, God Save the Queen. New York’s Museum of Modern Art owns a lithograph of that album cover now.

Yet curators said the lasting version of the Queen in the public’s memory will likely be one she intentionally projected: a royal who embodied duty and awe.

“She was really experienced at projecting an image of majesty and service,” said Alison Smith, the National Portrait Gallery’s chief curator. “This mystique was key, and the people loved her for it because we wanted some of that fairytale magic in our lives.”

From her glamorous coronation portraits by Cecil Beaton in 1953 to her grandmotherly Platinum Jubilee portrait released by Buckingham Palace three months ago, the Queen’s signature demeanour in images was to appear relatable yet also slightly aloof, Smith said.

That appearance of regal distance may have been an intentional move so that fellow world leaders, mostly men, would take her more seriously.

“The royal image has been one of their main weapons against the historic chauvinist preconception that queens must be weaker than kings,” historian Andrew Graham-Dixon wrote in an essay tied to a Sotheby’s Platinum Jubilee exhibition and sale this year.

Artists who painted her often picked up on her effort to subtly control her visual narrative.

In Justin Mortimer’s The Queen, the monarch comes off looking cheerily detached, by design. “I felt she was from another era,” Mortimer told the Journal in 2011 after painting the Queen’s portrait for the Royal Society for the Encouragement of the Arts.

Ever the diplomat, the Queen never spelled out her own opinions on the portraits made of her – or even on art in general. She seldom spoke about art she liked, or didn’t, Smith said.

Artists like Thomas Struth say they can tell she was fond of images taken in the 1960s by her brother-in-law at the time, Antony Armstrong-Jones, known as Lord Snowdon. Struth, who shot the queen with her husband in 2011, told Janet Malcolm in a New Yorker article, “It’s clear that the best pictures of Elizabeth and Philip are by Lord Snowdon, because he was a family member.”

The Queen wasn’t known to be a major collector like the Queen Mother, who bought impressionists along with contemporary British artists of her day.

Prince Philip was adept at painting watercolours, as is King Charles. It is unclear if the Queen ever picked up a paintbrush.

As sovereign, she served as the Royal Academy of Art’s “patron, protector and supporter,” visiting six times during her 70-year reign, the academy said. She also visited the National Portrait Gallery in the late 1960s, when Pietro Annigoni’s portrait of her was unveiled.

Sitting for portraits was part of her royal routine, but she didn’t necessarily relish the effort. Smith said the queen gradually shortened her “sitting sessions” from a 13-session process with painters in the early years to singular visits with artists and photographers that were limited to half an hour. This compelled painters to take photographs and then create her portraits off site rather than set up an easel to capture her likeness in real life. “She lost a little patience over the years,” Smith said.

What art she stewarded, mainly, was the trove within the charitable Royal Collection Trust, one of Europe’s last intact royal collections. It contains at least 7600 paintings, books, ceramics, armour and the Crown Jewels. Many of these pieces rotated onto public view during her reign through loans and dozens of exhibitions. Yet during the first 50 years of her tenure, she added only about 20 paintings to the royal collection – additions worth a few hundred thousand pounds combined, according to the Art Newspaper. Most of these were portraits of her or other historical figures.

A closer look at the images she sent out into the world reveal a monarch in near-constant change. Marcus Adams’ portraits of the Queen as a toddler in 1927 exude a cherubic liveliness. Beaton’s early photographs of her at age 19 show a willowy woman in a crinoline gown with puffed sleeves, relaxed before a Rococo backdrop that evokes Jean-Honore Fragonard’s The Swing.

By the time of her 1953 coronation, Beaton switched to formally elaborate backdrops, posing her between red velvet curtains to match the grandeur of her bejewelled crown and sceptre. From the 1960s onward, photos emerged that appear more spontaneous, showing her laughing or interacting with her dogs.

In a 2012 exhibit at Windsor Castle, The Queen: Portraits of a Monarch, the royal collection’s trust said the Queen agreed to pose as a way to commemorate state visits or significant anniversaries in her life or the country. Other sittings were transformed into coins, bank notes and stamps.

Since most of these commissioned portraits were delivered directly to state-owned collections or royal societies, the marketplace for images of her remains relatively thin. Dealers and auctioneers will likely start eyeing this arena more closely now.

In 2012, Christie’s sold Warhol’s 1985 royal-blue silk-screen of Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom for $US841,626. The year before, Sotheby’s sold Annie Leibovitz’s lush, 2007 portrait, Queen Elizabeth II, Buckingham Palace, London, for $US81,044. Leibovitz, the first US photographer invited to take the Queen’s portrait, recently confirmed to Vogue that she had to finish her shoot in 25 minutes or less.

In her final years, the Queen was often photographed with a wide grin and eyes that crinkled in matronly triumph. “She let her guard down because she knew she had our trust,” Smith said.

Because the Queen waited a year following her father’s death to ascend the throne and sit for her coronation portrait, Smith said it was likely King Charles III would wait as long to sit for his own.

“He’s also already pretty well documented.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout