Looking for Osama bin Laden in the Land of the Pure

Hiding in plain sight in a middle-class enclave, how did Osama bin Laden get away with it? The short answer: by being a good neighbour.

The media scrum was so tight I barely felt the hand rummaging inside my bag. I couldn’t have done anything about it anyway, my arms were pinned so closely to my sides by the crush of bodies inside the lavish Lahore compound of Pakistan’s then opposition leader, Nawaz Sharif.

It was early 2009, my first trip to Pakistan as a newly minted foreign correspondent – actually, my first trip ever to Pakistan – and by the end of that press conference, attended by the city’s media and hundreds of overexcited, conservative Islamic youths, I had been relieved of both wallet and passport. Hours later, in a suburban police station, my “fixer” – a term that does no justice to the local journalists lured with US dollars into babysitting foreign correspondents – stuck close as two officers wolfishly suggested I should be locked up for carelessness. I still have the police report promptly leaked to local media – which correctly noted my passport details but spectacularly misreported me as Eminda Ermaj.

It was a rocky introduction to a country I grew fond of in coming years, notwithstanding the late-night check-ins by intelligence agents, and regular shadowing as I stretched the limits of my visa at trouble spots around the country. Superficially, I fell in love with the beauty of Pakistan: its soaring mountains and long coastlines, the casual elegance of its people, its Mughal architecture, literary traditions, food, endangered Murree Gin, and its love of adornment on absolutely everything from shoes to trucks. On a deeper level, it was the country’s light and shade that fascinated me: the courtly manners and instinctive hospitality that ran parallel to the unflinching cruelties in the name of nationalism and religion.

My first encounter, however, proved good training for the extraordinary events that, two years later, would help derail Pakistan’s shaky Western alliance.

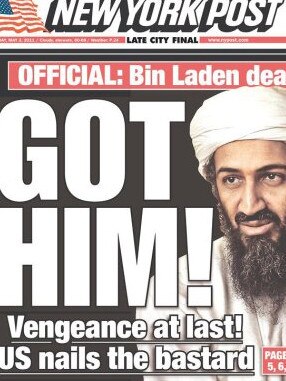

Looking back, you can draw a reasonably straight line from the US military raid on a suburban compound in Abbottabad on May 2, 2011, codenamed Operation Neptune Spear, which ended the life of Osama bin Laden, to the omnishambles in August last year that was the final withdrawal of US and allied troops from neighbouring Afghanistan.

When Pakistan’s political and security establishment awoke to the news that US Navy SEALs had crossed into the country just after midnight – allegedly without official knowledge or approval – to eliminate the world’s most-wanted terrorist, the ensuing two-way “trust deficit” so often spoken of would prove to be terminal.

The US alliance with Pakistan – the “Land of the Pure” carved from the bloody dissection of the subcontinent – barely survived the embarrassment to both sides of America’s key ally in its war on terror being definitively outed as a harbourer of terrorists.

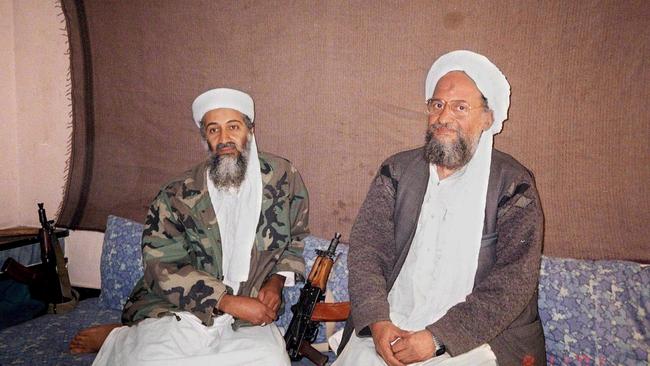

It was one thing to know Pakistan’s shadowy Inter-Services Intelligence agency was harbouring Afghan militants – the Taliban, Haqqani network, al-Qa’ida and the entire Quetta Shura (elders’ council) of militant leaders – even as US and NATO allies fought those same groups over the border. It was quite another to find that the man responsible for the 9/11 attacks on US soil that killed more than 3000 civilians was living peacefully in a garrison town a short stroll from Pakistan’s most prestigious military academy and two regimental barracks.

Islamabad was slow to anger that week, apparently blindsided by the brazen operation. As communities across the world celebrated the death of a notorious terrorist chief, Pakistani officials were deeply divided over how to respond. Should they play along and claim some credit for eliminating the world’s most wanted terrorist, potentially alienating millions of conservative and anti-American countrymen and women? Or should they protest a gross breach of trust by a powerful ally and risk allegations of institutional incompetence or terrorist collusion?

In the end, Pakistan chose a wounded combination of both.

But that short window of time in which the civilian and military leadership clashed over how to handle a foreign policy disaster and potential domestic crisis was long enough for Delhi-based correspondents to scramble over the border and up into the leafy highland region that once served as cantonment for British forces. Anyone without a current Pakistani visa was sunk. Islamabad’s reflex reaction was to shut down visa services to journalists clamouring to get in.

There was plenty more punishment to come, with new edicts issued every few days like angry thought bubbles. A humiliated Pakistan military demanded the US strip back its military presence. A week later, it ordered a review of its intelligence co-operation with the US. By November, the US military had been evicted from the Shamsi air base in Baluchistan, curtailing the CIA’s deadly drone campaign targeting militant commanders in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas bordering Afghanistan. The critical overland supply route through which US and allied forces shuttled armaments and equipment into Afghanistan’s battle theatre was also shut down.

Pakistan’s capriciousness, and the unpredictability of a supply route now captive to a deteriorating Cold War-era alliance, would be a contributing factor in convincing US president Barack Obama and his successors of the futility of their role in the Afghan conflict. Bin Laden’s death also removed a key obstacle to a US withdrawal from Afghanistan, though it would be another decade before the last American military plane would leave Kabul, plunging Afghanistan and the wider region into chaos.

A call from the Sydney newsdesk pierced the early morning silence long before it penetrated my sleep-deprived brain with the biggest news of the decade. I weightlifted my head off the pillow, cursing the weekend’s late finish, and stumbled into The Australian’s bureau – the third bedroom of our New Delhi apartment – to find the quickest route to Abbottabad, and enough fresh detail to pull together 1800 words before my noon flight.

It’s not easy to get from India to Pakistan speedily, thanks to their edgy bilateral relations, and it would take almost 24 hours to do so. On May 2, 2011, I joined an anxious foreign media pack travelling from Delhi airport to the far southern port city of Karachi– the only flight into Pakistan that day – back up north to Islamabad and overland to Abbottabad.

But that tortuous trip would be child’s play compared with the Russian roulette, that week, of getting in and out of Bilal Town, the housing estate on the edge of Abbottabad where bin Laden lived and died, as a wrong-footed Pakistan security apparatus shifted into high gear.

Bin Laden’s neighbours were mostly happy to talk about the mysterious occupants of the sprawling three-storey cement compound known locally as Waziristan Haveli, or Waziristan Mansion, after the Pakistan province that had become a militant hotbed for the Taliban, al-Qa’ida and the Haqqani network.

“In a friendly neighbourhood, where most other houses are built close together, the compound was built in the middle of a vast field across the road from other houses. Anyone who dared lean on the wall was warned to move on,” I wrote at the time. The local kids – predictably cricket mad – offered one of the first revelations when they boasted of the cottage industry that flourished out of the paranoia of the compound’s residents, who preferred to pay $US2 or $US3 for every cricket ball that sailed over the 5m perimeter wall than allow them to be retrieved.

The milkman was under instructions to leave 10 litres of milk daily at the front gate but not to ring the bell. There were no phone or internet connections to the house. They burned their own rubbish and brought in their own livestock for slaughter. It was more than enough grist for Bilal Town’s gossip mill. Many assumed the mysterious inhabitants were drug runners or Pakistani Taliban leaders. If anyone in that middle-class neighbourhood had speculated that the world’s most wanted terrorist might be living among them, playing Mortal Kombat and pacing the veggie garden, they were not sharing those suspicions now.

How did bin Laden get away with it? The short answer, it seems, was by being a good neighbour. The longer answer is one Pakistan continues to dodge to this day.

Arshad and Tariq Khan, the two brothers known locally as Big Khan and Little Khan who drove and ran chores for the bin Laden family, were said to have been kind and respectful – though Big Khan was also allegedly the key al-Qa’ida courier who unwittingly led the CIA to the compound. They shared meat from animals slaughtered inside their own cattle yard with their neighbours on Muslim Eid holidays, occasionally bought sweets for the local kids and even gave away some rabbits, which a couple of neighbourhood children happily showed me on a nearby roof terrace.

America’s audacious hunt for bin Laden ultimately would make gripping, cinematic drama. But on the ground in Abbottabad that week, the scramble for the story of how the architect of the 9/11 attacks had managed to live such a prosaic existence undetected, with three wives, a brood of kids and a hutch of bunnies, was equal parts cinema verite and slapstick comedy.

Within a few days of the raid, the security noose around the neighbourhood had been pulled so tight I found myself in an absurd game of tag: running arcs through the cauliflower and wild marijuana fields on the edge of the suburb, with armed, uniformed police giving chase and yelling, “Madam, madam!” at my back. On one occasion, I passed local kids selling scraps of genuine US Blackhawk, scavenged from the first helicopter that crashed into the compound wall as it hovered low over the property in the early hours of the morning. But there was no time for souvenirs. Unforgiving deadlines – Sydney is five hours ahead of Pakistan – meant having to run the gauntlet back into Bilal Town all over again in the late afternoon after hitching to the closest internet connection to file.

Amanda Hodge is The Australian’s Southeast Asia correspondent. This is an edited extract from Through Her Eyes: Australia’s Women Correspondents Hiroshima to Ukraine, published by Hardie Grant. Out Tuesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout