Let’s not inflame China tensions with talk of war

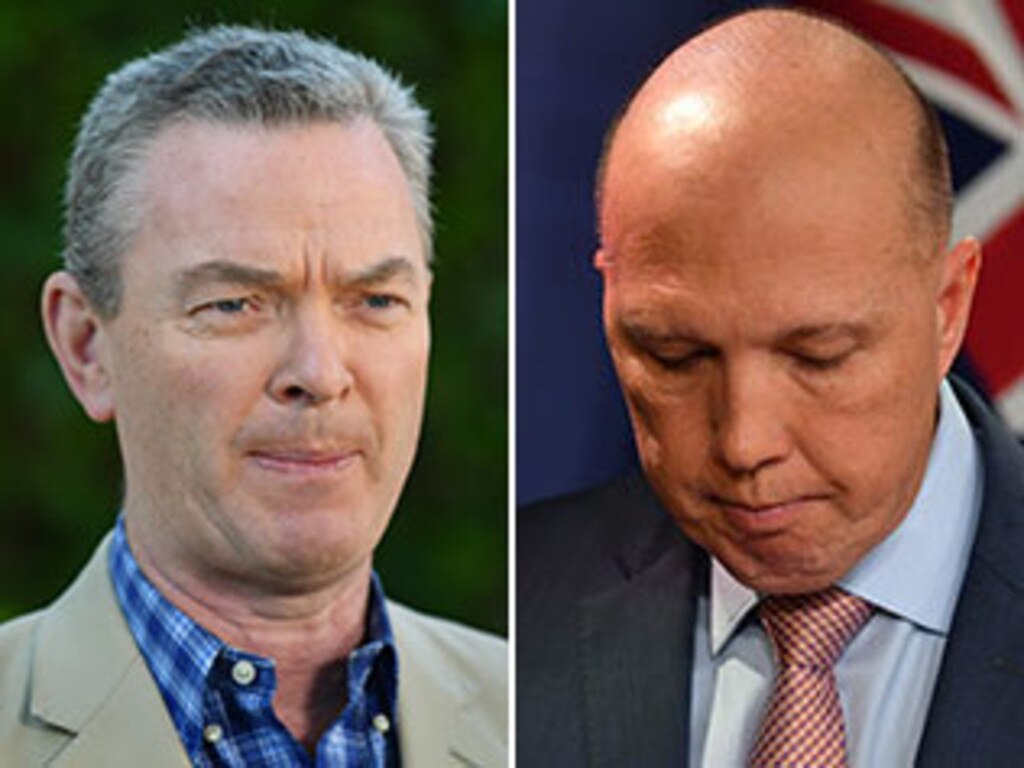

Instead of Christopher Pyne and his obsession with China’s military strength, what Australia needs right now is more of Peter Dutton.

Dressed up in his academic finest, replete with gown and cap, Pyne used the occasion to warn the assembled audience of “a possibility (that) we may well confront” a real war “in the next five to 10 years”. The reference was to a conflict between the People’s Republic of China and the United States plus its allies.

Pyne’s speech had the intended impact. It featured on Monday evening news bulletins. There was footage of the colourfully dressed award recipient in a grand old building with some soberly dressed academics behind him and an attentive audience in front. And the cameras really liked the “real war” reference.

And what about the impact? Well, Australia’s one-time defence minister was not very helpful. There is enough tension in the existing relationship between the governments in Canberra and Beijing without it being added to.

Peter Dutton, Australia’s recently installed Defence Minister, struck a more appropriate note speaking on Sky News on April 4. He said that “we can work in a collaborative way with the Chinese Communist Party … and make sure that, at the same time, we can work with others across the region”.

There is no question that Australia, among other Asia-Pacific nations, has reason to be concerned about China’s aggressive stance under the leadership of Xi Jinping with respect to the South China Sea and Taiwan, along with its breach of the one country two systems agreement which was to prevail in Hong Kong until 2047 and which ensured a degree of democratic liberties.

But it makes little sense to express concern about a possible conflict between China and the US and its allies. Sure, this may occur, but it may not. Pyne told his audience: “China’s military is very capable in the event of any conflict against the US and its allies around the western Indo-Pacific and Southeast Asia. Australia is one of those allies.”

This focuses on China’s strengths. But it overlooks the nation’s weakness — as reflected by its isolation in the region. China’s (somewhat undiplomatic) diplomats refer on occasions to Australia’s support for the Australia American Alliance and suggest that Australia’s position on China reflects that of the US. But Australia’s interest in encouraging the US to remain in the Asia Pacific and beyond is shared by such nations as India, Indonesia, Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Vietnam.

The fact is that, in Australia and elsewhere, predictions have been made which, if they had come to fruition, would have seen a conflict between China and the US by now.

Take Australian National University professor Hugh White, for example. In November 2014, White appeared in a debate on ABC TV Lateline with Alan Dupont. Asked by presenter Emma Alberici: “Are we going to see a war in our region, Hugh White?”, he replied: “I think that’s a possibility we can’t rule out.” White added that the situation in the Asia Pacific was “a little bit like what happened in 1914”.

Well, what happened in 1914 was the outbreak of a world war between Germany and France and Britain on its western flank and Russia on its eastern flank which lasted for four years. White’s prediction was made over six years ago.

Writing in The Sydney Morning Herald in March 2005, White suggested that “we may face a naval battle this year … between the US and Chinese navies, ostensibly over Taiwan’s independence”. Nothing happened. Ditto in late 2012 when White told Age readers not to be surprised if the US and Japan went to war with China in 2013.

It was not so long ago that White appeared to run the line that Australia should step back from its reliance on America and move closer to China. Now in his recent book titled How to Defend Australia (2020), White advocates that Australia should stand alone and double its defence expenditure to around 4 per cent of gross domestic product.

White’s current position is consistent with the argument that Australia should be militarily self-sufficient, as advocated by anti-communist operative B.A. Santamaria. Except that Santamaria, while expressing doubts about the usefulness of the Australia American Alliance, never wanted Australia to disengage from it.

At the time, Santamaria’s view on defence was mocked by many an ANU academic. So was his position on China — or, more explicitly, the Communist Party of China. These days Santamaria’s attitude to China — and that of similar minds at the time such as Frank Knopfelmacher, Sibnarayan Ray and James McAuley — would be fashionable. And that, in a sense, is a problem for China.

Contemporary politics in the US and Australia is deeply divided on numerous matters, with the exception of China. The US, under the presidency of Joe Biden, is moving to the left primarily due to the influence of left-wing operatives within the Democratic Party. But not in regard to China.

What currently unites left-of-centre and right-of-centre political activists in the US, Australia and elsewhere turns on China’s clampdown on democratic freedoms in Hong Kong and its cruel treatment of the minority Uighurs in Xinjiang province. Also there is substantial support in both nations for Taiwan.

The rise of China under Xi Jinping has been accompanied by reputational damage. No one knows what China might do in future years. But it’s possible that its projection of strength may be counter-productive.

In the meantime, Australia needs more speeches of the kind recently given by Dutton and his assistant minister Andrew Hastie on the need for the Australian Defence Force to be a fighting fit machine and on Dutton’s specific focus on where Australia disagrees with China — and less of Pyne’s obsession about China’s military strength.

Gerard Henderson is executive director of the Sydney Institute.

It’s a phenomenon of our time that some men and women who receive an honorary doctorate from one of Australia’s tertiary institutions say something likely to attain media attention. And so it came to pass on Monday when Christopher Pyne, the former Liberal Party member for Sturt in Adelaide –—and a one-time defence minister — received an honorary doctorate from the University of Adelaide.