Leaders danced to the toons of maverick master of the art Bill Leak

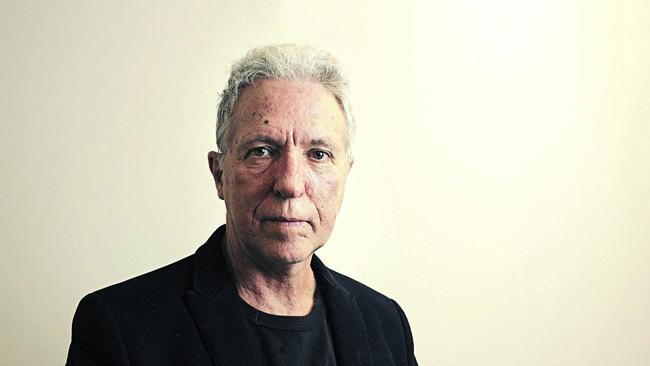

Bill Leak ‘could draw like an angel’ but was inspired by a devilish sense of humour that revelled in skewering politicians.

When he returned to Sydney after almost four years in Europe in December 1981, Bill Leak’s dream of becoming a successful artist was tantalisingly close.

He had absorbed all he could from the European masters, and held two solo exhibitions in southern Germany, where he’d been living, which, although small, were well received and reviewed.

He had sent samples of his work to Brett Whiteley, the enfant terrible of the local art scene, which had elicited enthusiastic encouragement and an invitation to hang out at Whiteley’s studio in Surry Hills.

And he was returning with Astrid, his strikingly attractive German wife, the perfect companion for the exhibition openings he dared to imagine he would soon be hosting.

But it wasn’t just a desire to, in English writer Samuel Johnson’s words, “appear considerable in his native place” that was driving him home.

Bill had adored Germany but the humourlessness and reserve of German culture were anathema to him.

He yearned to be back among fast-talking, brash larrikins like himself.

Bill managed to get a few of his canvases into a group exhibition at Robin Gibson Gallery, in inner-city Darlinghurst, a suburb with a growing cohort of wealthy, successful gay couples. Bill’s contribution to the exhibition consisted of a series of nude studies of a male dancer friend.

Bill and Astrid were arriving at the gallery to check it out one day when they saw Elton John leaving. He was wearing a loud shirt and orange-check shorts. Bill pulled a $20 note from his wallet, offered it to John, and said, “Here you go, Elton, buy yourself a decent pair of strides, mate”.

Elton laughed it off and kept walking. Inside, Bill asked Gibson what John had been doing at the gallery. Gibson replied he’d expressed some interest in Bill’s nudes. Bill whispered to Astrid, “I think I’ve just done myself out of a few large sales”.

Bill held a solo exhibition at Robin Gibson, but it wasn’t nearly as lucrative as he expected.

His mum, Doreen, consoled him by reminding him that he’d always loved drawing cartoons, and maybe he should dabble in it on the side.

Bill’s fascination with cartoons had been piqued a few years earlier in Germany when his sister, Lynne, sent him an anthology of work by Bruce Petty, of The Age. He realised that great cartoons sometimes had the same compositional techniques as great art.

More importantly, he didn’t think his interest in these supposedly ephemeral creations would compromise his own art. Rather, it might enhance it. He didn’t need much convincing to give it a try.

Bill approached Lindsay Foyle, the art director at The Bulletin, some time in late 1983, and was invited to submit any political cartoons he could draw every Friday, as half a dozen other freelancers did, and then wait till the magazine hit the stands the next week to see which, if any, were selected. One of Bill’s made the cut on his first attempt.

“It was an almost ecstatic experience when I saw one of my drawings in print,” he told journalist Ann Turner in an oral history for the National Library.

“It was almost as though all of a sudden I’d found my true vocation and I became completely obsessed with drawing cartoons.”

Soon he was also submitting to Penthouse and Playboy, but The Bulletin was his main focus. He would often stay up all night on Thursday drawing cartoons, drop them off at The Bulletin’s office in Park Street, in the city, then go to his studio up the road in Darlinghurst to sleep. He was paid $40 per published cartoon, but the low hourly rate didn’t bother him.

“I suddenly found that it placed me in this really unique position of being able to not only, you know, shout and scream at the radio when I was listening to question time or getting hot under the collar when I was reading the papers, but actually being able to vent my spleen on paper and know that the people that I was upset about and the things that were making me angry I was actually able to comment on in a public way and in a way that I knew they would have to see,” he told Turner.

“I really enjoyed it, it was exhilarating and there was really no turning back from that moment.”

Newspapers were entering a golden era at the time, led by magazine-style inserts that added fashionable cachet to their already authoritative products.

Fairfax newspapers – The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age – were particularly good at it, inserting Good Living for epicureans and The Guide for entertainment each week.

John Sandeman, the new head of the art department at the Herald, was under instructions to put together a stable of world-class artists. The department had previously been filled with illustrators who produced generic, realistic ink portraits that made their subjects more handsome than they actually were. John replaced them with larrikins – artists who invariably made them uglier.

“That’s where Bill came in,” he says.

Bill wasn’t to know Fairfax was on a recruiting drive to revolutionise the department. But he did know that there were few other employers in town that suited his new career direction.

“You won’t believe this, but Bill was nervous,” Sandeman says. “This was big stakes for Bill – it really was make or break.”

Bill’s folio was bursting with brilliance, although little of it, if any, had been published. “This was raw talent. He was clearly a great draftsman. His training had done him proud. It was obvious the bloke could draw like an angel.

“The secret about the media is being at the right place at the right time. For Bill, Fairfax in the 1980s was the right place and right time.”

The Herald and The Age were among the five most profitable newspapers in the world at the time, thanks to their reams of classified ads, famously dubbed “rivers of gold” by Kerry Packer, who coveted them. The place was flush with cash, which also made it a magnet for eccentrics.

John’s deputy, John Moses, says Bill was “clearly identifiable as the top talent” in a stable full of stars: Jock Alexander, John Shakespeare, Michael Fitzjames, Tony Edwards, Jenny Coopes, the late Amanda Upton, Kerrie Leishman, Mark Knight, Andrew Ireland, Reg Lynch and Paul Newman.

The eclecticism of the artists’ room allowed for a collegial style of working. Surprisingly, the banter was seldom political. The focus was instead on original ideas. “All we wanted to do was put out these crazy beautiful drawings because the world needed crazy beautiful,” says Reg Lynch. “That was our mission.”

Bill’s mission was grander.

He not only wanted to create great newspaper art, but his ambition was for it also to be the best. He won his first two Stanleys, the annual awards by the Black and White Artists Club (now the Australian Cartoonists Association), for Artist of the Year and General Illustrator, in 1987. He won two more Stanleys in 1988, four in 1989 and another three in 1991.

That same year the rules were changed to limit entries to two categories per artist, although the club says Bill’s dominance was not the reason for this change. He also won Walkleys for Illustration in 1987, 1989 and 1990, and the coveted Cartoon award in 1983. (This run of awards would continue after he left Fairfax to join The Australian in 1994. He would eventually wind up with 20 Stanleys and nine Walkleys.)

The toughest job most days was the illustration for the next day’s Opinion page. The topic was often not decided until after midday, and whoever got the job needed to go down to the editor’s office and explain his or her idea. Most of the artists dreaded doing this, but not Bill.

“Bill was more political,” Lynch says. “He liked to meet people like Malcolm Turnbull and Bob Hawke. He was interested in them. He loved playing and yakking with the big blokes.”

The most important gig of the week was to create the artwork to accompany the Alan Ramsey column in the Saturday edition, one of the most widely read and influential weekly columns in the nation at the time. Bill admired Ramsey, and was often the first pick for the job.

This led to him stepping in as the daily cartoonist on The Australian Financial Review for 2½ months while the incumbent, Rod Clement, was on holidays, starting on September 25, 1992.

Four days into this role, he did a cartoon about a decision by the High Court finding the Australian Constitution implicitly protected political free speech. Bill lightly ridiculed the decision by suggesting that it only encouraged politicians to be more intrusive.

Little did he know that, 24 years later, free speech would come under serious threat in Australia and that, despite significant death threats and widespread vilification, he would become one of its most passionate defenders.

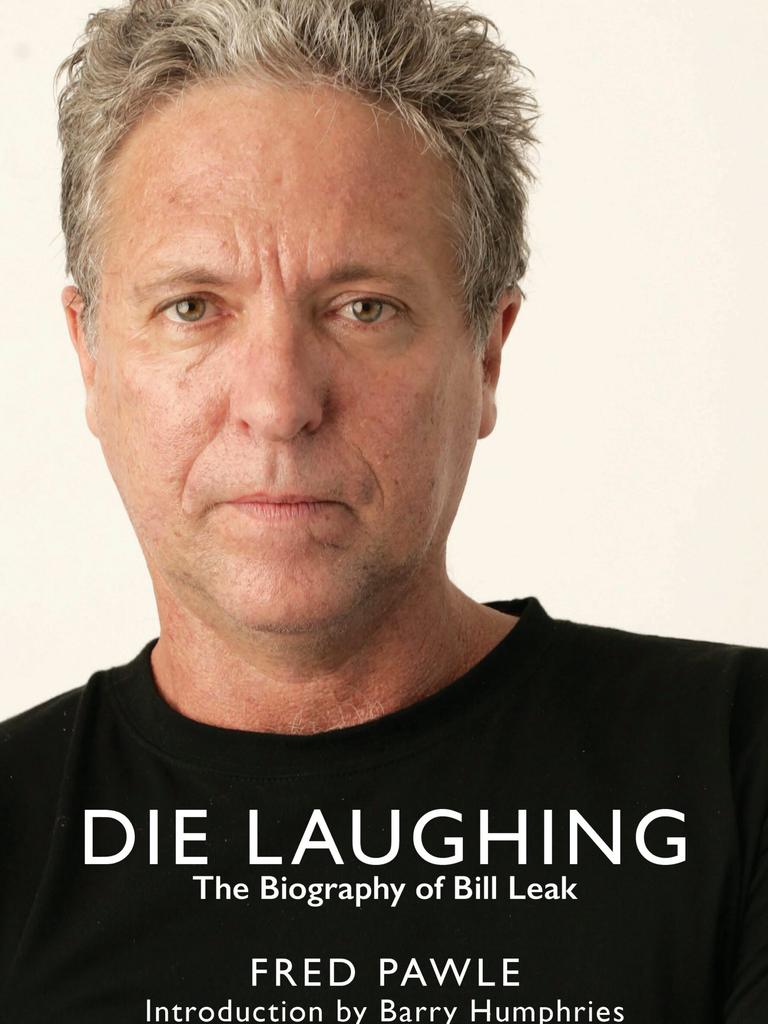

This is an edited extract from Die Laughing: The Biography of Bill Leak, by Fred Pawle, published by the Institute of Public Affairs. Out Monday. To purchase your copy, go to dielaughing.org.au.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout