Last minute advice proves decisive for migrating family

Alan Howe’s family, migrating from Britain, was destined for Fremantle but, by chance, ended up in Melbourne.

My parents’ marriage was one of convenience. At least inasmuch as all my mother had to do after she married Jack Howe was knock the letter “s” from her own surname.

Mum’s father was a soldier in the British Army for every day of both world wars. My dad came from mining stock in Newcastle upon Tyne. He was one of several sets of twins, but the only child to make it to the age of two. Not that uncommon; things were grim in the north – and this was before the Depression.

My mum Pat moved about with her parents as her dad, Reginald, was posted here and there – including Jamaica, where her brother was born. She said she went to the hospital to see him for the first time and was very disappointed that he was a white baby. The only one. He too would be burdened with the name Reginald, a family tradition my mother cancelled.

World War II ruined my parents’ educations and dad left school to paint ships at the Swan Hunter yards on the lower reaches of the Tyne River. It was dirty and dangerous. A man a week was killed there. He joined the RAF and played drums in their band. That was safer.

Pat joined the Women’s RAF and they both found themselves serving in Singapore during what was known as the Malayan Emergency.

This was a nasty communist uprising targeting rubber plantation owners who were mostly British. And they were influential back home; their sway was great enough to ensure the uprising was never declared a civil war – just an emergency: had it been a war (and presumably we would now know it as the Rubber War) Lloyd’s of London insurers would not have been liable to pay out for damages.

A few British plantation owners were assassinated, as was the high commissioner, and the Emergency saw the first use of chemical defoliants against jungle-based combatants.

There was a large British contingent there and, by all accounts, there was a robust social life among the RAF staff. Pat met Jack on a blind date and they married at the Singapore Catholic cathedral off Orchard Road. Mum said that was the last blind date she was ever going on. The WRAF did not employ married women. Mum had to return to England. Dad drummed on through Aden and Sudan.

Living next to the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough, Hampshire, mum started a family and dad worked as a boilermaker, sign writer and carpenter – skills learned over his eight years of service.

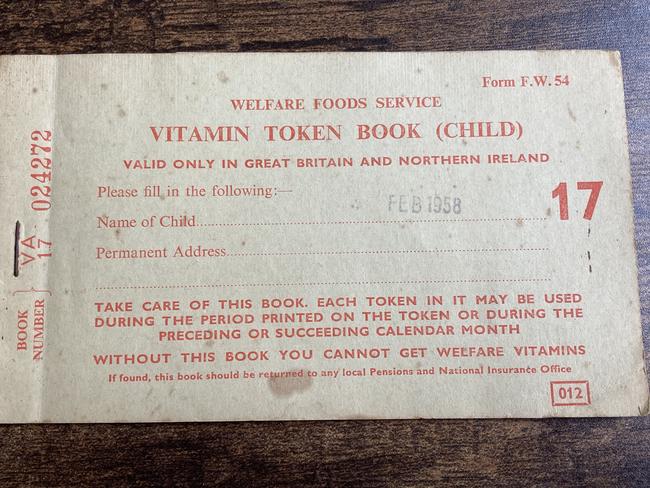

But these were the grey, post-war years when austerity ruled: best documented by the Ministry of Food’s Vitamin Token Book (Child) ration stamps I keep to this day – Orange Juice Drink 5d, Cod Liver Oil free. Britons lived frugally, surrounded by vacant bombed-out factories and homes in the front gardens of which surviving neighbours grew vegetables.

Wartime hero prime minister Winston Churchill was back in Downing Street. Aged 80 and still obsessed with global powerplays, he was seriously unwell and seriously out of touch. Even King George VI considered asking him to step down.

Britain and its allies had won the war, but the peace was a stony anticlimax. By then, Arthur Calwell’s immigration tidal wave had arched up over Australian shores. The British left from wherever they could: Liverpool, Belfast, Glasgow, Southampton and the appropriately named Grimsby.

My dad saw a newspaper advertisement inviting migrants to try life in Australia for a subsidised fare of £10. That is about $1900 each for mum and dad. Kids were free. Unlike our aunt and uncle, dad must have checked the weather forecast. My cousins migrated to Montreal and remain frozen there to this day. We set off for Fremantle. Jack liked the sound of its weather and beaches and, while we knew not a soul in Australia, dad may have been aware that many sons of Newcastle – Geordies, they are called – had made a home there. They still do. My friend Hank B. Marvin, legendary guitarist for the Shadows, and one of the most influential musicians of the rock era, has lived in Perth for decades.

Unfortunately, I was too young and remember nothing of the trip across the Mediterranean and down through the Suez Canal. It had recently and controversially been nationalised by Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser and was front page news in The Times the Saturday morning I was born.

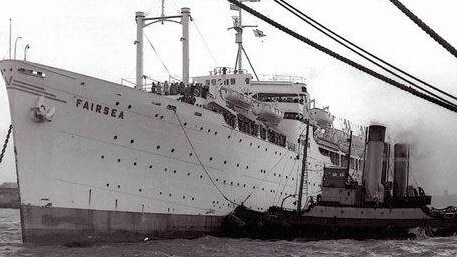

We were aboard the Sitmar Line’s Fairsea. It had served as a troop carrier after the war and was chartered by the Australian government in 1955 to transport migrants here, 1800 at a time.

I imagine all the children aboard had a great time, but I suppose the parents, while excited at a new start in a foreign land, were also daunted about the unknown challenges. Who knew what Perth had in store, or what Australia would be like? For working-class migrants back then it would have been considered a one-way trip. Not many would have thought they would be able to afford the passage to return, nor have a job that allowed them three months off – six weeks back to England and six weeks sailing back to Australia. The development of the Boeing 747 in 1969 changed that but, still, it wasn’t until 1974 that more people flew from London to Australia than arrived by boat.

It was midwinter 1958 when the Fairsea docked at beautiful Fremantle. Here we were: Australia and five lives about to start anew. Pat watched as our meagre belongings – mostly in sturdy wooden boxes dad had made back in Farnborough – were put ashore. The families milled around the deck where a gangplank was being attached to the ship. Suddenly, a man armed with a broad Australian accent and a loud hailer asked for everyone’s attention. Who was getting off in Fremantle but did not have a job arranged, he asked. Jack and other men – he wasn’t talking to the women – put their hands up. He motioned them over to an area towards the bow of the ship.

He advised the gathering that Perth and Western Australia were in recession and it would be hard to find work. But he added that Victoria’s economy was in good order and, if they wished, they could stay aboard and travel to Melbourne, the next stop.

The men were given 15 minutes to think about it. In those minutes, and in vital ways, the futures of us all would be decided. Would we live Perth lives? Or would we sail on, unexpectedly, to Melbourne to chance the family’s arm in Victoria?

Pat said we should get off. It had been the plan all along. And we were due at a migrant hostel in Perth as arranged. Jack said no. Three kids and no job. We were off to Melbourne and Station Pier.

Days later we were living in half a Nissen hut at the Nunawading Migrant Hostel. My parents never visited Western Australia and never set foot in Perth or Fremantle. Neither, as far as I know, have my siblings.

Pat and Jack lived almost all of the rest of their lives in the suburbs of Melbourne. So too my brother and sister. My parents’ brave call to travel to the other end of the earth has worked out.

In 1994, having returned from a stint on the New York Post during which I visited the legendary gateway to America, Ellis Island, I wrote to then Victorian premier Jeff Kennett suggesting that, through Station Pier in Melbourne (the greatest single point of entry in the population of this country) the city owned a big part of that story and that we should have an immigration museum that recorded and celebrated the stories of those people who made the journey.

Mum and dad were at its opening in 1998. I met the Queen there in 2000.

“Populate or perish” had been Calwell’s catchcry. We populated and flourished.

I wandered about for 13 years – working on newspapers in London, Sydney, Adelaide and New York – but returned to edit a newspaper in Melbourne, and then a second.

I wouldn’t change a thing. But I still sometimes wonder in what ways would life have been different had mum prevailed that day in the Port of Fremantle.

About 15 years ago, I was in Fremantle and walked over to the dock where the Fairsea had stopped over all those years ago.

I called my mum: “You’ll never guess where I am.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout