Knocked down by polio, raised up by determination

Despite paralysis, my dad went on to become a doctor and pioneer in rehabilitation medicine.

Nurses delivered a breakfast tray decorated with tinsel to Brad’s bed on the morning his final exam results were released.

It was two weeks before Christmas 1953. Brad was relieved to pass, but the nurses in Sydney Hospital’s Ward 10 were visibly elated as they propped up their patient to pose for a newspaper photo. They’d not just witnessed the young man’s difficult years in hospital but played a vital role keeping him alive. This was vindication day.

Almost four years earlier, Brad was a fit 22-year-old and six months away from completing his degree at the University of Sydney to qualify as a doctor when he was struck down with polio.

He was fortunate to survive. Such was the severity of his illness that he needed an iron lung to breathe for the first three months. He endured years more, lying on his back, unable to move.

Brad eventually restarted his final year of medicine from his hospital bed. He was wheelchair-bound with muscle-weakness paralysis in both arms and legs for the rest of his life.

The idea that someone in the 1950s with one of the nation’s worst cases of poliomyelitis could become a practising doctor and father like any other person seemed inconceivable then. A short existence in a nursing home was more likely.

Brad, after whom I’m named, lived a full life. He was the father of me and my brother, Rolf.

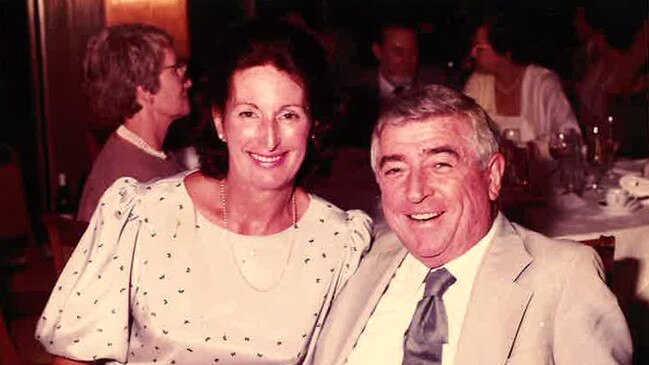

Serendipitously, for him and us, he met the woman who would become our mother when she was a Sydney Hospital nurse and he was a patient – though she was working in a different ward on the day he became Dr Norington.

The polio epidemic of the ’50s and others were awful. If polio is forgotten by many as Covid-19 wreaks havoc, it is because vaccination programs from 1955 onwards almost eradicated the disease.

When our father contracted polio, there was no vaccine: earlier vaccine trials in the ’30s had been abandoned amid failure.

Polio is a highly contagious virus, usually spread by faecal or oral contamination on the hands of infected people. It causes paralysis by attacking the nervous system that controls a person’s muscles.

While some infected during epidemics had no symptoms, others suffered permanent paralysis in one or more limbs. In the worst cases, such as Brad’s, polio caused severe paralysis and could be fatal if it attacked the nerves that control breathing.

Brad was diagnosed with polio in late March 1950 when he lived with his parents at Coogee, in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. He was a few weeks into starting his sixth year of medicine and feeling run down.

Waking up one morning with flu-like symptoms, Brad missed his usual surf before university and stayed in bed. As hours passed, he experienced difficulty moving his arms and legs, which prompted his mother to call a doctor.

With the doctor suspecting polio, Brad was transported by ambulance to Prince Henry Hospital, an isolation facility at Little Bay in Sydney’s south.

Brad’s parents were told to expect the worst when he fell unconscious while inside the tubelike iron lung machine, a negative-pressure precursor to ventilators.

Standing behind a glass protection screen during one of many visits, Brad’s cousin Pam Harris remembers: “He was barely awake, his eyes were closed, and he couldn’t speak.

“We thought we were going to lose him. But that day we could see through the window in the iron lung. He moved a finger. It didn’t seem much, but it was like a breakthrough.”

Brad did wake up as his respiratory damage eased. The downside, now fully conscious, was realising his paralysis was probably permanent. He entered the darkest phase of his illness, thinking all was lost.

Things were about to change. By early 1951, Prince Henry’s polio wards were overflowing.

No longer contagious or acutely ill, Brad was moved to Sydney Hospital, a teaching hospital in the heart of the city.

It was a cheerier place and the medical superintendent, Norman Rose, placed Brad in a ward with high-turnover patients recovering from surgery. His bed was in a corner, near the pan room, which was a positive because of the regular passing traffic: nurses talked to him and turned pages of the many books he devoured in his immobile state.

Brad was also in a noticeably different frame of mind. Despite some mental lows, he’d found peace with himself and his predicament. His sense of humour was back.

One nurse in particular, Jacqueline Kelly, caught his eye. She was 19, a first-year trainee with dark hair and strong, fair Irish looks. He found her striking and easy to get on with.

Jacqueline continued to visit Brad after her shifts when she was transferred to other wards. Brad said later he never gave up hope of qualifying as a doctor, but Jacqueline would seem a key inspiration.

The opportunity came along with the hospital’s tough but fair-minded medical superintendent. Admiring Brad’s determination, Rose became an important mentor and used his influence with the university senate.

And so Brad was permitted to restart sixth-year medicine in 1953 and sit 14 final exams with a dispensation from one – practical surgery. He dictated his exam responses because, although having regained enough strength in his right hand to use a pen, he could not write at speed.

Rose helped in other ways. As a white-coated junior resident doctor at the hospital in 1954, Brad moved upstairs with others, with Rose assigning a wardsman to get him out of bed, bathe and dress him, and wheel him to work in the outpatients’ department.

Brad physically examined some patients, but he was mostly allocated those where diagnosis based on a verbal exchange was sufficient.

With his once great hopes of becoming a surgeon dashed, psychiatry was an option, but Brad was not interested. He considered a future in dermatology but settled on the nascent specialty of rehabilitation medicine.

This was perfect fit for a doctor who could potentially help others with debilitating maladies resume lives with purpose – while being a living example.

Brad travelled solo to England aboard the SS Oronsay in January 1955 (with a ship steward’s daily assistance) because no qualification in rehabilitation was then available in Australia. For the next two years he studied and worked as a junior registrar in London, passing exams for a diploma in physical medicine.

There was more to the plan. Before leaving Sydney, Brad had proposed to Jacqueline and they agreed she would follow him to London in October 1955 after qualifying as a registered nurse.

A fortnight after she arrived, they were married. It was a quiet, modest wedding, in part to avoid more warnings from Jacqueline’s family and friends against marrying a man to whom she would be a full-time nurse and carer.

Back in Sydney by August 1957, the couple found a home in the city’s northwest and Brad took on a full workload as a specialist at Mt Wilga Rehabilitation Centre, Prince of Wales Hospital and Concord’s Repatriation Hospital. He treated many hundreds of spinal injury, burns, amputee and stroke patients over three decades.

As a father, Brad was gentle, consistent with his nature. He preferred to use his wit, which was central to the success of his marriage, in guiding his sons’ lives.

My brother and I knew that if Dad wheeled to our bedroom doors on the (odd!) occasions we transgressed, then we were in trouble. He did not need to say much, such was his quiet authority. We were a close family, drawn closer by our need to work together caring for Brad and taking some physical demands off Jacqueline.

When Brad was named Father of the Year in 1981 – 40 years ago this weekend – he said in his acceptance speech that fathers should “set an example for their children and provide a background of restraint as well as affection”.

Brad lived until 62 when he was not expected to survive past 40. During a doctor-to-doctor chat in 1990, the famous cardiac surgeon Victor Chang said he was confident a heart bypass would be successful. Brad agreed but declined. “I think I’d survive the surgery, but not recovery,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout