King Charles will prioritise religious reconciliation in fractured world

‘Spiritual searcher’ Charles has long contemplated how, as king, he will relate to faiths beyond Protestant Christianity.

Defender of the Faith is just one of the titles a British monarch takes. It has referred, historically, to the sovereign’s role as head of the Church of England and guardian of its Protestant character.

But at the door of St Anne’s Anglican Cathedral in Belfast, King Charles III saw what it really means in 2022. He was greeted by the leaders of the local Jewish, Muslim and Hindu communities.

Inside, the service of remembrance for Queen Elizabeth II was led, unsurprisingly, by an Anglican bishop. But the Catholic Primate of Northern Ireland, along with his counterparts from the Presbyterian and Methodist churches, read the deeply symbolic prayers for the late Queen.

Charles has been contemplating for a long time how, as king, he will relate to faiths beyond Protestant Christianity.

In 1994, during an interview with his biographer, Jonathan Dimbleby, he made what might have been an incidental comment. Rather than being Defender of the Faith he might prefer the more capacious term “Defender of Faith”.

It opened him up to the charge of being a religious relativist, one who believes all religions are basically the same, none more grounded in truth than the next. But Charles is less the religious relativist and more the religious realist. He knows his realm – especially Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – are multi-faith and increasingly faithless. Within a wider Commonwealth that includes India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria and Malaysia, Christianity is almost certainly a minority religion.

In 2015 he clarified his stance, saying he would accept his guardianship of the Church of England without qualification, while stressing: “I mind about the inclusion of other people’s faiths and their freedom to worship in this country. And it’s always seemed to me that, while at the same time being Defender of the Faith, you can also be protector of faiths.”

In emphasising a more pluralist view of religion, Charles is building on his mother’s work. She began a serious and effective outreach to the Catholic world, meeting five popes and presiding over the first papal state visit to Britain, Benedict XVI in 2010.

Her last papal meeting, radiating obvious warmth, was with Pope Francis in 2014. And let’s not forget her historic voyage of reconciliation to the Republic of Ireland in 2011 and her speech, partly in Gaelic, that prompted the president at the time, Mary McAleese, to simply say: “Wow.”

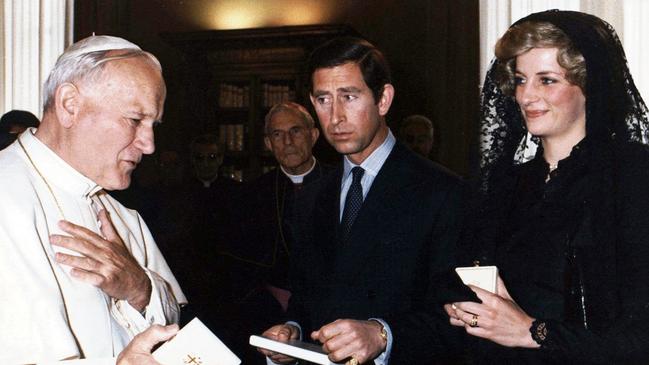

Charles’s own commitment to ecumenism stretches back decades. In 1985, he and Princess Diana met John Paul II at the Vatican and even asked to attend a papal mass. Buckingham Palace overruled the couple – a mass consecrating bread and wine as the body and blood of Christ, via transubstantiation, was still a bridge too far.

Charles also is fascinated by Orthodox Christianity, especially given that his father, Prince Philip, was baptised Greek Orthodox before converting to Anglicanism to marry Princess Elizabeth.

The new King seems to revel in the contemplative and mysterious elements of Orthodoxy, spending time in the male-only monasteries of Mount Athos in Greece.

Arguably the most attention-grabbing of the King’s religious interests is his engagement with Islam. He even studied Arabic so as to read the Koran in its original text. Almost 30 years ago, opening the Oxford University Centre for Islamic Studies, to which he has given his official patronage ever since, he rejected the idea, gathering pace at the time, of a clash of civilisations between the Islamic world and the West. He spoke directly to British Muslims, calling them “an asset to Britain”.

As fascinated as he is by the rich culture and history of the Islamic world, he also knows where extremism leads. In 2018, he spoke passionately about the persecution of Christians in the Middle East at the hands of the Islamic State group, and he reportedly has made large private donations to help Christians fleeing their ancient homelands.

For the new King, religious reconciliation in a fractured world is as great a priority as dealing with climate change.

Charles’s own practice of Anglicanism is thought to be a little higher “up the candle”, as they say. He enjoys the swelling hymns, ancient and modern, and the richer liturgy of High Anglicanism. He certainly likes the structure and language of the Prayer Book.

The Queen was no “happy clapper” – no lover of contemporary religious music, casually dressed clergy and interminable sermons requiring visual aids – but she was a more conventional Low Church Anglican who preferred to have the service done and dusted within 45 minutes.

She was like her grandfather, George V, a straightforward Bible-reading Christian. But Charles has the element of the spiritual searcher about him. Like his late father, he is known to grill preachers after the service about the finer points of their sermons. They are on notice.

Andrew West is presenter of The Religion & Ethics Report on ABC Radio National.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout