King Charles III coronation: Can the royal fairytale live on?

The British monarchy has had an impressive track record of reinventing itself. Whether the magic of the monarchy retains its popular mass appeal as the world’s pre-eminent fairy story remains to be seen.

British coronations have a history, which is to state the obvious but a point that needs unravelling. Buckingham Palace’s official souvenir program for events next week is full of images and references to “Moments of Majesty” past: from William the Conqueror’s crowning on Christmas Day 1066 embroidered on the Bayeux Tapestry, a mock-up of George III’s coronation robes, to the role of royal consorts in history.

Pride of place is given to the previous two ceremonies: the crowning of King Charles’s grandfather, George VI, and his mother, Elizabeth II. Both the 1937 and 1953 events are good points of comparison as we try to understand the state of play of the British monarchy today.

Inside Westminster Abbey, audiences will be encouraged to follow six phases of what is essentially a medieval rite, some of it dating back to Anglo-Saxon kingship: the recognition, oath, anointing, investiture (which includes the crowning), enthronement and homage.

Like his mother’s ceremony in 1953, we will not see the King anointed. We are told it is the most sacred part of the pageantry when the sovereign’s breast and head are consecrated with holy oil, sourced from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (a first). The King abandoned plans for a see-through canopy that would have allowed the cameras in on this part of the ceremony. Royal sources insisted that he felt he must respect the anointing as part of his intimate relationship with God.

The Archbishop of Canterbury has been keen to define the coronation as a Christian service of prayer, and Britain is the only European monarchy to retain a religious ceremony.

Reformed Protestantism will loom large on the day, with the King’s oath pledging himself as Defender of the Faith (originally a Catholic title conferred by the Pope on Henry VIII) and of the true Protestant religion in Scotland. From time to time, the King has qualified this reformation rigour, saying that he also sees his role more plurally as protector of faiths, but the oath will remain.

Many other parts of the ceremony are what historians call modern invented tradition. From the 1880s onwards, the time of Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee, the British monarchy became increasingly splendid, public and popular, after years when the Widow of Windsor steadfastly refused pageantry with a purpose.

Successive royal events – the Victoria’s funeral in 1901, the coronation of her son, Edward VII, and grandson, George V – finessed a type of imperial royal theatre, some of which we will see repeated on May 6. The outward and return carriage processions through London’s West End streets flanked by Commonwealth and British armed forces will run; so will the Buckingham Palace balcony appearance by the King and his family, first undertaken by George V and Queen Mary in 1911.

Some features of this modern spectacle have been abandoned or dramatically scaled back in the interests of a lower-key emphasis and implicit political choices.

There will be no silk stockings and knee breeches for the King or any of the peerage; the number of guests has been reduced substantially in the interests of health and safety; and the length of the ceremony has been shortened.

Overall, there will be less extravagance than the nearly three-hour long ritual that installed Elizabeth II. Queen Camilla will not wear the crown made for King Charles’s grandmother but Queen Mary’s crown, thus avoiding the use of the Koh-i-Noor diamond, which India demands should be returned.

The King also has signalled his support recently for serious research via the Royal Archives into the monarchy’s relationship with transatlantic slavery. In 2021 his eldest son, now Prince of Wales, insisted the royal family “is very much not racist”, but as yet there has been no apology.

Ancient rites, invented modern ceremonial and things that are actually new will be crafted together over the coronation weekend.

The King is committed to a monarchy that respects longstanding traditions while reflecting his role as head of a modern inclusive nation and Commonwealth. Watch out for how modernity and tradition are conjoined in the ceremony as a hallmark of King Charles’s reign.

Ceremonial apart, modern monarchy is inseparable from the media because the press, newsreels, and then radio and television are the main ways that mass society has experienced royalty. Elizabeth II’s coronation was not just splendid and popular, it was seen by nearly a quarter of the world’s population. In 1950s Britain, BBC TV was fast becoming a privileged interpreter of the social world, with broadcasters such as Richard Dimbleby enhancing royal gravitas and high-toned education for the viewing public.

But TV also made the pageantry more international and more intimate, despite the queen’s initial reservations about the cameras inside Westminster Abbey. A European link-up extended coverage to parts of Western Europe, and within hours recordings of the TV transmission were being seen across the Atlantic on the Canadian and US networks.

Australia did not get a TV service until 1956, but canned film of the ceremony was dispatched posthaste on a Qantas airliner to arrive in Sydney in record time, from where it was shown in cinemas across the country.

Monarchs and dictators of the past had paraded their greatness on relatively small stages; this was a different type of spectacle where time and place were hugely compressed. International audiences saw Elizabeth II only slightly later than the guests in Westminster Abbey and the crowds outside.

In Britain, an audience of 20 million watched the queen for the best part of 2½ hours, sitting in front of their own or their friends’ televisions. TV encouraged family and communal viewing and an uptick in the purchase of sets.

Retailers used the royal byline to promote this must-have symbol of the new consumer society. My own mother, recently married, told of a strict pecking order among her in-laws, about who was allowed to sit close to my grandfather’s recently purchased 12-inch TV. As a newly arrived family member, she was put near the back of the sitting room so that elderly Auntie May could get nearer.

TV also encouraged greater immediacy and personal familiarity with the monarchy.

“This time I was there taking part,” one young man said who had listened to the 1937 coronation on the wireless but now watched it on the telly.

TV will continue to shape King Charles’s media coverage; an estimated 300 million viewers are predicted to tune in on May 6, though the number is hotly contested. Britain’s anti-monarchy campaign group Republic prefers to concentrate on the majority world audience who will not watch, but streaming on phones, computers and other electronic media will now make the event part of the digital age, extending the monarchy’s virtual presence.

Buckingham Palace has its own dedicated website, of course, but it is in the more informal world of Facebook, Instagram and the Twittersphere where younger audiences in particular will see the ceremony and in new ways, if they watch it at all. They will surely splice it with screen shots and messages of quite different stuff: photos and videos of themselves, friends, food and adverts – some of it funny, some of it scurrilous.

Alongside the media glamour and the official pomp, most modern coronations have also had disruptive backstories. They reveal a lot about gender and royal status because they have often involved royal women being treated badly.

As far back as 1821, Queen Caroline, the estranged wife of George IV, had the door of Westminster Hall slammed in her face as she tried to get into her unpopular husband’s extravagantly expensive crowning. Trying to find another way in, this time she was blocked by a line of armed soldiers. Supportive crowds shouted “Shame, shame”, as Caroline left in her carriage.

Fast-forward 100 years to 1937 and the coronation of George VI. This time there were two personae non gratae: the recently abdicated Edward VIII and his wife, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. There was no invitation for Edward and Wallis. Family tensions and recriminations ran high as the duchess (aka Mrs Simpson) was deprived of a royal title, but the ex-king with his star quality and international glamour still attracted large-scale support across the empire.

A woman from Devon confided: “We have lost a good king (Edward VIII) – one who had sympathy with the working classes … they got rid of him.”

In 1953, when the royal family was leaving Westminster Abbey, the queen’s sister, 22-year-old Princess Margaret, was caught on camera conspicuously brushing a speck of fluff off the tunic of her lover, Peter Townsend. Margaret was high-spirited to the point of indiscretion; the media’s foil to Elizabeth’s decorous charm and regal allure. The princess’s display of intimacy telegraphed to the media her romance with this divorced RAF group captain and royal equerry 15 years her senior.

Evoking memories of the abdication drama, two years later Margaret was forced to make a painful choice between love and duty. In 1955, she renounced her lover under pressure from the government, the Anglican Church and members of her own family. But many ordinary women and men thought otherwise. “She ought to have married him,” was the resounding verdict from a Battersea typing pool, echoing widespread public feeling.

In 2023, there is no queen consort banging at the Abbey door. The King’s care and devotion to Camilla is palpable; she will be styled Queen, not the lesser title of queen consort or princess consort. But there remains the legacy of Princess Diana, now carried by Meghan and Harry’s claims and counterclaims.

Harry’s recent statement that he has always felt “slightly different to the rest of his family” and that his mother felt the same underlines his position as the most recent in a long line of coronation renegade royals.

Harry will be in Westminster Abbey on May 6 and the King quite rightly has spoken about his pride in both his sons. But Meghan, Harry’s wife, declined her invitation, ostensibly on the grounds that it coincides with her son Prince Archie’s fourth birthday. Social media opinions are sharply divided about the Sussexes’ decision, to say the least. Supporters are praising Meghan for asserting her independence from a family she has exposed as unwelcoming and hostile to people of colour. Opponents have attacked her for snubbing her royal in-laws in language that is frequently unrepeatable. Given the couple’s appetite for publicity and its material importance to their lives, Harry and Meghan’s backstory is by no means concluded for the King and his immediate family.

All of which brings the coronation around to the current state of public opinion – about the event itself and about the British monarchy more generally. Mass Observation, a British social research organisation born out of the abdication crisis, has been busy tracking public responses to royal events since George VI’s crowning on May 12, 1937. Royal marriages, jubilees, funerals as well as coronations have all been put under MO’s vox pop spotlight.

The group’s findings tell us much about changing public responses to the monarchy. The attitudes are much more complex than committed royalism, on the one hand, or republicanism on the other because modern monarchy touches the world of the emotions and human feelings in contradictory ways.

Reverence and respect, envy and scorn are all part of the mix.

In 1937, the crowds responded not just to the pageantry but by wanting to get closer to royalty, part of the monarchy’s new place in ordinary life. Kissing couples in London’s Hyde Park marvelled at the procession “like something out of a fairy story”. But a Cambridge graduate went to bed feeling “sick, disappointed and fed up”. One young journalist admitted: “Saw part of the procession (and then a) pub crawl. Delighted to be able to drink in the middle of the afternoon.”

All this was part of the desacralisation of royalty and it continued across the 20th century, fostered by the popular press and then by the coming of television.

In 1953, sociologists and archbishops claimed the ceremony as an act of national communion, while Conservative politicians and empire loyalists heralded the coming of a new Elizabethan era to rival the age of the first Elizabeth. But at street level something different was happening. A hunger for excitement and spectacle, to be sure, that was emphatically “in colour” after the years of post-war austerity and rationing. Equally, warmth towards a young woman with all the glamour of a Hollywood star, who was unmistakably royal and an “ordinary” wife and mother as well. Elizabeth II juggled these competing roles with regal aplomb. Sceptics and even some ardent republicans found themselves drawn to the queen. A 21-year-old bank clerk who had previously thought of Elizabeth II as supercilious and remote felt a rising excitement when she came past in the State Coach.

There were more negative commentaries, too. People often referred to the 1953 event as a “London thing” that meant less to people farther north, especially in Scotland. Shopkeepers north of the border said they could not sell “Elizabeth II”, partly because of nationalist objections about the queen’s true title there. Yet the event planted monarchy firmly inside the nation’s popular culture. One local woman in a poor part of Fulham, London, put it simply about the young queen’s crowning: “It’s something … to remember. We’ve always liked her … Let’s hope she’ll be happy, and we’ll all have peace.”

This May, Mass Observation invites British people to record events in their local area over the special bank holiday weekend, so that it can piece together a snapshot picture of the nation. What will they discover? Will there be the same level of popular support for the new King and Queen there was 70 years ago? British society had been transformed, and more than once, since 1953. “Winds of Change”, to quote prime minister Harold Macmillan in 1960, has spanned not just the country’s experience of the end of empire and the rise of the welfare state, but then the new social movements in the 1960s, mass consumer society, followed by the cult of individualism, the free market, and the racial diversification of the country, to name only some.

The 1937 coronation had been an exercise in national stabilisation after the abdication turmoil of the previous year. It was the last great imperial display, affirming the prestige of the monarchy when Britain’s world power status was already eclipsed by the two superpowers, the US and the Soviet Union.

Robert Menzies in Australia and Winston Churchill at home might have looked towards a bright future for the British Empire as the reinvented Commonwealth, but no amount of window-dressing could conceal the fact the monarchy’s place in the post-war world order was diminished.

What of the situation in 2023? The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which the King leads as head of state, is fragmented and break-up of the union is still a possibility.

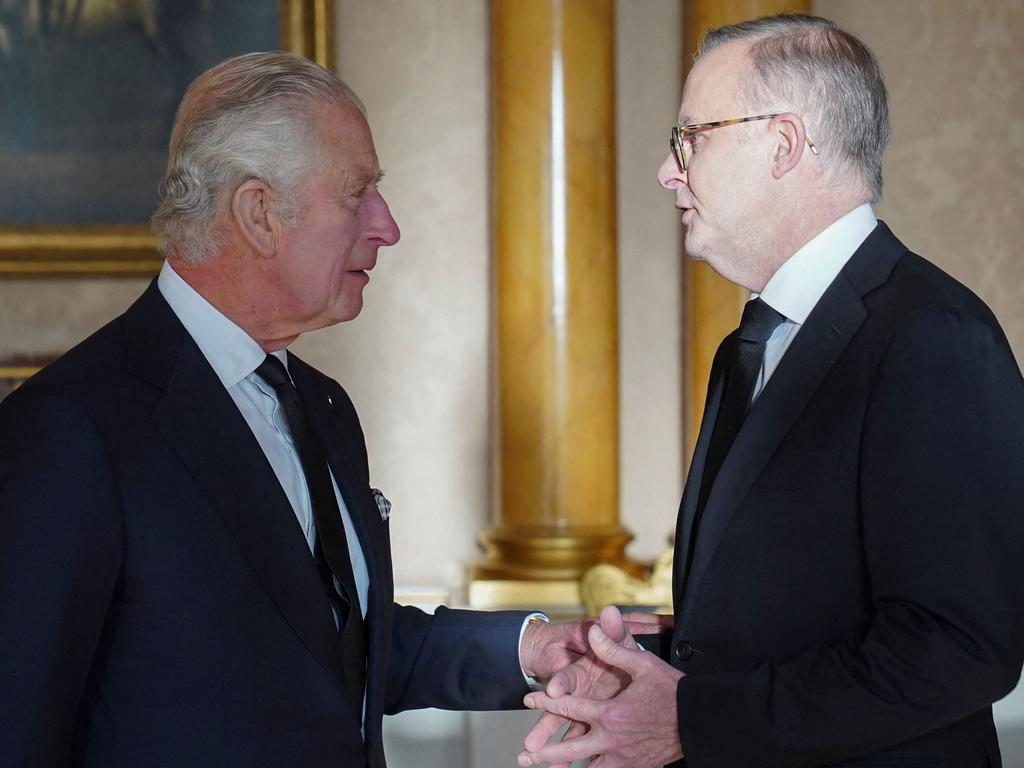

Brexit has fractured Britain’s post-imperial foreign policy, tied as it was from the 1970s to Europe. The Australian government has made clear its commitment to prepare the country for transition to a republic in the medium term. Anti-monarchist sentiment has grown in the Caribbean with the controversies over British slavery accelerating. Jamaica will move to a republic by 2025 and Antigua and Barbuda is demanding a referendum. More immediately, King Charles will be crowned amid an ongoing cost-of-living crisis and a European war. The coronation feel-good factor may be elusive, but feel-good is currently in short supply across many countries, both monarchies and republics.

The British monarchy has had an impressive track record of reinventing itself at many crisis points across the 20th century. During the Great War it was touch and go whether the institution would survive, but it did in the face of considerable odds. The same was true under very different circumstances after the death of Princess Diana. King Charles is in the business of incremental reform of the crown’s role and style. He is already more informal and hands-on than his mother ever was – expect more changes of this kind in the months ahead. All the major political parties in Britain are committed to the monarchy, so republicanism remains a pressure group – although if Australia were to go for full self-rule, the balance of forces in Britain might alter substantially. Whether the magic of the monarchy retains its popular mass appeal as the world’s pre-eminent fairy story remains to be seen next week. In the meantime, it is surely fitting to wish the King and Queen well.

Frank Mort is emeritus professor of history at the University of Manchester in Britain. He is writing a book about the British monarchy in the 20th century, The People’s Crown, to be published by Oxford University Press.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout