Last month, aggrieved TikTokers throughout the US inundated the phone lines of congressional offices, prompting some politicians to switch them off. A pop-up alert within the app warned, “Congress is planning a total ban of TikTok. Let Congress know what TikTok means to you,” urging users to input their postcodes for the phone details of their local representative.

However, the campaign only galvanised support across the aisle for legislation compelling the video-sharing app to divest from its Chinese parent, ByteDance, or face expulsion from US app stores.

TikTok warned its users the law would breach their “Constitutional right to free expression”, “damage millions of businesses” and “destroy the livelihoods of countless creators”. Yet the attempt to mobilise the app’s 170 million American users through questionable claims did little to quell anxieties about Beijing weaponising TikTok to shape US public opinion through misinformation.

In the event of a TikTok shutdown, creators will migrate to other social platforms. Meta’s Facebook/Instagram Reels, YouTube Shorts, and Snapchat’s Spotlight feature now all offer clones of TikTok’s short-form vertical video format. When India banned TikTok in 2020, following Chinese military aggression in its disputed northern border region, 200 million Indian TikTokers quickly adapted by moving elsewhere.

Labelling the bill a “total ban” is also hyperbolic, given the bill primarily addresses its Chinese ownership. In 2000, the US forced the Chinese owner of Grindr to offload the gay hook-up app to US owners amid concerns that data encompassing sexual preferences and HIV status of US officials could be misused by the Chinese Communist Party.

TikTok’s proliferating pro-Hamas content has awakened many to the toxicity and social power of its recommendation engine, with views of videos featuring pro-Palestinian hashtags eclipsing pro-Israel content by a factor of 80. Yet the bill doesn’t touch the US first amendment liberties of even virulently anti-Semitic accounts.

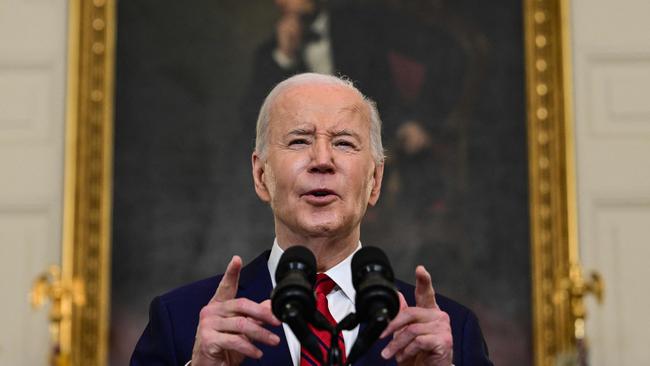

TikTok’s ham-fisted campaign suggests the resurgent momentum of crackdown talks caught the platform off-guard. Tensions reached fever pitch in 2020 when president Donald Trump tried to force TikTok to separate from ByteDance. Still, the issue receded after the courts overturned his executive order, which Joe Biden rescinded on assuming the presidency. After the bill’s latest version passed through congress, Biden signed it into law on Thursday AEST. The legislation, which grants ByteDance up to 12 months to secure a non-Chinese buyer, was strategically embedded within an omnibus bill to approve urgent foreign aid for Ukraine, Israel and Tawan, expediting its passage.

With ByteDance poised to sue, Australian policymakers will watch its legal manoeuvres closely. Last year, Australian Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus banned TikTok from government-issued devices but stopped short of extending this to government contractors or critical services operators as in some US states.

However, in a recent report, the Senate’s Select Committee on Foreign Interference Through Social Media recommends that if the US government acts to force TikTok’s divestiture Australia should consider a similar approach.

Some employees fault TikTok for being slow to lobby congress in earnest, underestimating the existential threat faced, and becoming complacent about a debate that had simmered for years. Its public policy team began reporting directly to chief executive Shou Zi Chew, a Singaporean businessman, only in late 2022, when congress summoned him to testify.

TikTok had focused mainly on appeasing Washington through a $US1.5bn initiative, Project Texas, which uses Oracle servers to isolate US consumer data to US soil and provided the enterprise IT vendor with access to its algorithm and source code.

But the costly undertaking placated few sceptics, with the company’s assurance that American user data is inaccessible to Chinese employees having proved a canard. In December 2022, TikTok acknowledged that ByteDance engaged in surveillance on several American journalists to identify the sources behind leaks, accessing the reporters’ data and monitoring their movements.

TikTok is notorious for its aggressive data collection practices. In a white paper analysing TikTok’s source code, Australian cybersecurity firm Internet 2.0 judged TikTok the worst offender among social media apps for its gratuitous data-grabbing: “The application can and will run successfully without any of this data being gathered … the only reason this information has been gathered is for data harvesting.”

TikTok repeatedly claims it has never shared data with the CCP, but even if taken at its word, it would have no choice if asked to do Beijing’s bidding. In 2018, Beijing shut down its meme-focused comedy app Neihan Duanzi (literally, “implied jokes”), prompting ByteDance founder Zhang Yiming to apologise for undermining “core socialist values” and failing “to direct public opinion in the right way”. In 2021 ByteDance shut down its education apps when the CCP banned for-profit tutoring of school curriculum subjects.

Last year ByteDance’s former US head of engineering, Yintao Yu, filed a wrongful dismissal lawsuit against the company. He described a “culture of lawlessness”, with a Beijing-based unit of CCP members installed in ByteDance to “guide the promotion of core values” inside the company; they had a “god credential” enabling them to monitor data collected, including from US users. “This was a backdoor to any barrier ByteDance had supposedly installed to protect data from the CCP’s surveillance,” the filing read.

But the threat of TikTok becoming a platform for propaganda offensives remains perhaps the strongest case for the law. Its recommendation system has regularly suppressed content on topics contentious to the one-party state, such as Falun Gong, Tiananmen Square, and even #BlackLivesMatter and #GeorgeFloyd. AI is equipping foreign adversaries with the ability to disseminate misinformation at an unprecedented pace and scale; and President Xi Jinping repeatedly has proven his commitment to spreading anti-liberal ideology and suppressing dissent beyond China’s borders more aggressively than any Chinese leader since Mao Zedong.

Under Xi, the CCP also has tightened its grip on the Chinese tech sector.

China’s internet watchdog shut down Marriott’s website for listing Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau and Tibet as separate countries, prompting the hotel chain to issue a grovelling apology condemning “separatists”. Mercedes apologised for “extremely incorrect information” following a Chinese outcry over an Instagram post featuring a car on a beach, overlaid with a Dalai Lama quote: “Look at situations from all angles, and you will become more open.” Closer to home, a cyber attack on Sydney gaming scale-up Immutable blocked users from logging into its digital trading card game after it offered to pay the prize money lost by a pro-Hong Kong player booted out of a competitor’s game.

Under Xi, the CCP also has tightened its grip on the Chinese tech sector. In February China Renaissance chairman Bao Fan, a dealmaker behind many Chinese tech giants, re-emerged after disappearing for a year as part of an anti-corruption crackdown on tech, only to announce his resignation from the Hong Kong-listed investment firm “for health reasons”. No less than Alibaba founder Jack Ma vanished for three months in 2020 after criticising the Chinese government’s interference in the country’s banking industry, with Beijing retaliating by launching a monopoly probe into the e-commerce behemoth.

Some argue the TikTok bill sets a dangerous precedent of retreating from the open nature of the globalised internet. But it only slightly readjusts the heavily lopsided playing field between the US and China, which has long blocked Western tech companies, despite its local equivalents often operating on US-built server infrastructure. TikTok itself doesn’t meet the stringent demands of mainland China’s Great Firewall; ByteDance’s Chinese TikTok equivalent, Douyin, allows minors under 14 to access it for up to 40 minutes a day and just watch age-appropriate content.

Likely in pre-emptive retaliation against the TikTok law, Chinese regulators a week ago instructed Apple to pull chat apps WhatsApp, Threads, Telegram and Signal, from its Chinese app store. Although these apps were barred in China, users were able to access their services using VPNs.

ByteDance corporate structure is byzantine, to say the least. TikTok’s parent, ByteDance, has its head office in Beijing but is incorporated in the Cayman Islands. But the Chinese government sits on the board of one of ByteDance’s Chinese incorporated subsidiaries; previously called Beijing ByteDance Technology, it rebadged with the name of TikTok’s Chinese equivalent, Douyin, as Beijing Douyin Information Service Limited. The Chinese state’s representation on the three-person board overseeing ByteDance’s primary revenue spinner Douyin – a seat Beijing secured through a 1 per cent shareholding in 2021 – means the regime is never far from home.

But the TikTok bill debate has also been fascinating for what it shows about the US political system – in particular, money flows around Washington.

Trump has since backflipped on TikTok, potentially seeing an opportunity to secure young voters increasingly disenchanted with Biden, but most likely to secure his relationship with Jeff Yass, co-founder of Susquehanna International Group, which owns a 15 per cent stake in ByteDance.

Within days of meeting the libertarian mega-donor, who has contributed $US46m ($70.5m) to Republican candidates this election cycle, the former president declared: “There are a lot of young kids on TikTok who will go crazy without it”, and writing on Truth Social: “If you get rid of TikTok, Facebook and Zuckerschmuck will double their business.”

ByteDance’s other US investors, such as General Atlantic, Sequoia Capital and Coatue Management, were uncharacteristically quiet about this year’s ban bill. With worsening geopolitical tensions with Beijing, venture capital firms are likely to save their political capital on Capitol Hill to shaping a favourable regulatory environment for their AI bets.

If a sale moves ahead, realistic bidders may be limited. The big tech companies that could afford TikTok, potentially valued at more than $US100bn, would have a hard case to make in light of US antitrust laws and political pressures surrounding the concentration of power in Meta and Google.

Microsoft briefly explored purchasing TikTok’s US, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand operations in 2020, seeing strategic value in building on its 2016 acquisition of LinkedIn to gain a larger social media footprint. TikTok also would give Oracle a foothold in the consumer market. Former US treasury secretary and Trump loyalist Steve Mnuchin also has assembled a consortium of investors to bid for TikTok.

However, even if Beijing did agree to sell TikTok – and that is unlikely, with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute estimating that it has invested $US6.6bn into building its global media presence across the past 15 years – Beijing sharing its algorithm and source code would seem improbable, limiting the app’s value to suitors.

Without the algorithm-powered recommendations and its regular updates transferring to a new owner alongside TikTok’s data and user base, the experience could degrade precipitously.

In some respects TikTok may have lost its battle already, with the cloud of a potential divestment spooking investors.

ByteDance’s profits grew 60 per cent in 2023 over the prior year, with its $US120m revenue approaching Meta’s $US135m, but it is trading on the secondary market with an enterprise value of six times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation, compared with Meta (22x EBITDA), Alphabet (20x) and Tencent (12x).

Moreover, with its uncertain future, many advertisers have been shy about entering into long-term relationships with TikTok or its recent e-commerce play TikTok Shop, contributing to the platform’s losses of several billion dollars against estimated revenue of $US20bn last year. Savvy influencers, mostly multi-platform already, will focus on increasing their surface area on other platforms, inevitably at TikTok’s expense. With TikTok’s growth already plateauing, we need to look no further than Twitter/X to see how rapidly an ecosystem can devolve as its creators, users and advertisers move elsewhere.

(Given the risk of a creator exodus, it is perhaps timely that TikTok is developing AI avatars to “complement” human creators, promote products and read scripts generated by advertisers, although early signals suggest they are less effective than human influencers.)

Its sizeable investments in TikTok Shop demonstrate the importance of TikTok diversifying revenue streams away from advertising. Short-form videos are less conducive to advertising revenue than YouTube’s longer formats, which helps explain why TikTok has started experimenting with YouTube-length videos of up 30 minutes. But these bets to help TikTok become profitable also underscore how commoditised social platforms are becoming, with YouTube also offering its TikTok counterpart Shorts.

With more than 50 per cent of TikTok’s users now over 30, it can lay less claim to being the primary platform where youth culture trends take shape. It is too early to say RIP to TikTok, but when its demise comes, its absence will be little felt.

In Australia, TikTok has 8.5 million users. However, TikTok Australia no longer has any ByteDance representatives on its board, with its last representative, Tian Zhao, resigning last July. These moves provided cold comfort to the Senate select committee. TikTok, it writes, was “reluctant to provide witnesses sought by the committee, and evasive in their answers when they finally did agree to appear”. The committee accuses the company of engaging in “a determined effort to obfuscate and avoid answering the most basic questions about the platform, its parent company ByteDance and its relationship to the Chinese Communist Party”.

Throughout the Senate inquiry, TikTok’s Australian staff reprised their familiar argument that Australian data was stored in Singapore and the US, not China. Still, they acknowledged that TikTok’s China-based staff had accessed Australian consumer data and could influence the recommendation algorithm.

Unsurprisingly, TikTok Australia could not point to any legal basis to support its position that it would refuse to share information with the Chinese government if requested. Beijing’s 2017 National Intelligence Law stipulates that “any organisation or citizen shall support, assist and co-operate with state intelligence work”; and in a one-party state without an independent court system, ByteDance can forget avenues for appeal.

Despite Australia being what John Garnaut has described as “the canary in the coalmine of Chinese Communist Party interference”, our economic dependence on China has made many of our leaders reluctant to confront the CCP’s covert intrusions. But the view that prevailed throughout the Bill Clinton and Paul Keating eras that economic engagement with China would spread liberal values, modernisation and democratisation now seems fanciful.

As Australian-Chinese policy analyst Alex Joske has argued, “downplaying the threat of foreign interference only serves to embolden the CCP and undermines Australia’s ability to protect its sovereignty”.

In ASIO’s 2024 threat assessment, director-general Mike Burgess describes espionage and foreign interference as more prevalent than ever, having “surpassed terrorism as Australia’s principal security concern … if we had a threat level for espionage and foreign interference, it would be at … the highest level on the scale”.

In his memoir, Malcolm Turnbull recalls being briefed by ASIO on becoming prime minister in 2015: “While many nations sought to spy on Australia, China represented by far the bulk of detected activity … Their appetite for information seemed limitless … It was on an industrial scale … They do more of it than anyone else, by far, and apply more resources to it than anyone else … (and) they’re not embarrassed by being caught.”

Turnbull recalls, during their last phone call, Trump being “impressed and a little surprised” by his world-first decision in 2018 to exclude Huawei from its 5G rollout, as a hedge against future Chinese aggression. The following year Trump effectively prohibited American firms from doing business with Huawei.

Just as Turnbull’s Huawei decision marked a key moment in his evolution from an earlier more conciliatory, optimistic approach to the China relationship, the TikTok debate offers Anthony Albanese a similar reset opportunity. Unlike Huawei, ByteDance has never benefited from Beijing’s financial investment, but a platform with 8.5 million Australian users that a hostile adversary can manipulate makes it no lesser a national threat.

While the legal manoeuvres for TikTok US are just beginning, the US political debate is essentially over. In Australia, though, it has hardly begun. The US bipartisan consensus gives the Albanese government political cover to protect our sovereignty by following the US approach; and, like Biden, to stare down the kids.

Ben Naparstek is a growth consultant and former Amazon executive who recently led Finder’s international businesses. He has been editor of Good Weekend and The Monthly magazines.

More Coverage

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout