Jacinda Ardern’s policies won’t help the Kiwis fly

New Zealand has big problems but judging by the election campaign neither side seems to care.

She won’t have to worry about quitting, as she promised this week should she lose on Saturday.

Her Labour government, which snuck into power in 2017 in a deal with colourful populist Winston Peters, is within a whisper of winning an outright majority in NZ’s parliament, according to recent Roy Morgan polling. It is riding a wave of popularity set off by the island nation’s internationally acclaimed response to the coronavirus.

In contrast to Thunberg’s native Sweden, NZ shut its borders and implemented one of the world’s strictest lockdowns. Now, more than six months on, it has suffered only 25 deaths from COVID-19, far fewer than almost any comparable country. It barely had a first wave.

“The biggest shift in voting intentions is among the over-60s, who think she’s saved them,” says one former senior minister in the previous National Party government.

However much she did, it won’t change a grim economic reality: NZ in the space of half a year has blown its savings, smashed its two pistons of economic growth — tourism and immigration — and embarked on one of the world’s most ambitious money-creation programs.

“Until now the economy has been growing because of rapid rates of immigration and the associated demands on the sheltered sectors of the economy,” says Graham Scott, a former NZ treasury secretary.

The five million or so tourists NZ enjoyed each year have gone, obliterating the nation’s biggest exporter earner.

Net migration of 86,000 over the year to March will collapse to 5000 this year, the government reckons, with little prospect of any revival without a COVID-19 vaccine.

NZ is the economic canary in the policy mine that the coronavirus pandemic has created, pursuing radical policies from a rickety base. Before the pandemic the country ranked last in the OECD for multi-factor growth and fourth last for labour productivity growth.

Kiwi students, like ours, have been steadily falling down the global pecking order for reading, maths and science.

“It’s an economy that has been growing fat rather than tall,” Scott tells Inquirer. “We’ve been importing people to come in and build houses and associated infrastructure for themselves in effect.”

The election campaign provides little indication that either major party wants to shake the economy out of its funk.

“Australia has significantly higher productivity than NZ, average incomes are significantly lower here at around $NZ50,000 ($46,000) to $NZ60,000,” says Robert MacCulloch, an economics professor at University of Auckland. Since 1970 NZ’s GDP per capita has fallen from 85 per cent of Australia’s level to 78 per cent.

“There is a big macroeconomic adjustment in front of us. There’s near silence about what are we going to do about it. Both main political parties hope the economy grows its way out of its problems and avoids a tough adjustment.”

Labour’s policies include planting one billion trees, a 100 per cent renewable-energy target by 2030, a new, much higher, top rate of marginal income tax of 39 per cent for those on incomes above $NZ180,000, and doubling the number of sick days workers receive to 10 a year.

“Most new policy initiatives proposed in the run-up to the 2020 general election range from trivial at best to economic sabotage at worst,” concluded the New Zealand Initiative, a Wellington based free-market think tank.

Labour’s platform centres around spending an extra $NZ3.7bn on health and education “initiatives” over four years, and a wage subsidy scheme for 40,000 jobs for the long-term unemployed costing $NZ310m over two years.

“Both parties should have proposed some quite profound reforms of the welfare state and health system,” MacCulloch laments, noting that health consumes around 10 per cent of NZ’s GDP compared to 4 per cent in Singapore, with similar outcomes.

“It’s a big, bureaucratic and cumbersome system. In the middle of one of the biggest health crises for 100 years I find it remarkable that neither party has proposed any reform of the health system,” he adds.

Reflecting some of the policies in the Coalition’s budget last week, the National Party under new opposition leader Judith Collins would allow businesses to fully deduct new investments up to $NZ150,000, and introduce a tax rebate worth $NZ50 a week to the typical NZ taxpayer.

It’s promised an extra $NZ31bn on infrastructure over the next decade, no match for Labour’s $NZ42bn over the next four years.

“The virus has been quite a gift for the Ardern government in the sense that it allowed Labour to talk about its ‘wellbeing’ framework: We’ll make a sacrifice in terms of locking down and closing borders and even to the extent it hurts the economy it’s a price worth paying,” says MacCulloch. “It’s forced the National Party into a position where the more they try to say we want to open up, Labour has successfully put them in position of looking like they are prioritising GDP ahead of people’s lives.”

NZ’s GDP tumbled 12 per cent in the second quarter, almost twice as much as Australia’s did over the same period.

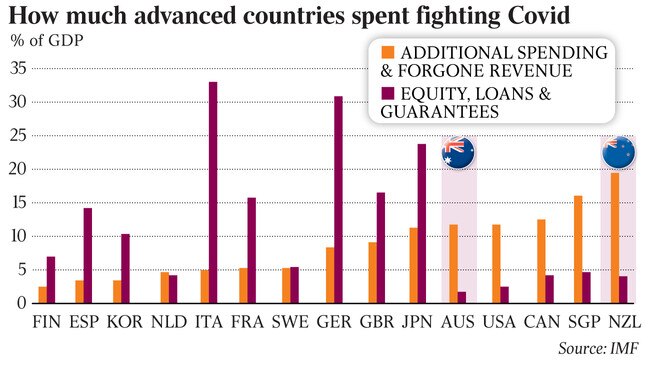

The combination of the government’s extra spending and lost tax revenue through the crisis was equivalent to almost 20 per cent of GDP, more than any other developed nation, according to the IMF’s latest world economic outlook, published this week.

Similarly, the government’s $NZ14bn wage subsidy scheme, its version of JobKeeper, flowed to more than 60 per cent of workers, compared to about 25 per cent in Australia, and more than any other scheme did.

The price of saving lives has been huge, according to NZ economist Martin Lally, who has advised Australian and NZ government price regulators. The hard lockdown policy prevented the deaths of 1000 people at a cost of $NZ8.5m for each year of life saved, according to his analysis.

That $NZ8.5m figure is 190 times greater than the $NZ45,000 value public health experts had ascribed to a year of life before the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Consistency would require spending $NZ22bn to extend the lives of 1000 people suffering from heart disease, cancer or diabetes, which is more than the entire annual spending on healthcare in NZ,” Lally says. But it’s unlikely that will be happening, given the state of the government’s balance sheet post-pandemic. Debt as a share of GDP is set to soar from 19 per cent last year to 55 per cent by 2024, according to the government’s pre-election fiscal update, which itself is optimistic.

Net worth, a broader definition that includes the government’s assets, is set to plunge from $NZ143bn to $NZ44bn, over the same period.

“We have a governor of the central bank like none we’ve had before,” says Scott.

“He badgers the banks to relax lending criteria, telling them to be courageous. Curiously, a year ago he was insisting they increase their capital ratios because they were too risky.”

The Reserve Bank of NZ, which is laying the ground work for “negative interest rates” later this year, has a money-creation program that dwarfs Australia’s.

It is buying $NZ750m a week of government bonds and has promised to buy $NZ100bn by the middle of 2022, which would be equivalent to more than half of net outstanding government debt by that time.

By contrast, the Reserve Bank of Australia has bought around $60bn of state and federal government debt, less than 10 per cent of the outstanding total.

“The view of the short-term outlook from outside NZ is more pessimistic than how people are seeing it here,” notes Scott.

Indeed, the government sees economic growth falling 3 per cent this year, while the OECD has pencilled in negative 10 per cent.

Similarly, the unemployment rate is forecast in the government’s budget papers to peak at 7.7 per cent next year, compared to the OECD’s prediction of 8.9 per cent.

Whatever the outcome, NZ’s government (and to a lesser extent Australia’s) is playing a high-risk game, pinning the country’s economic fortunes on an effective vaccine arriving reasonably soon.

If it doesn’t, how will the country engage with the rest of the world?

Everywhere else the coronavirus is becoming endemic; 30,000 cases in one day in France alone this week, for instance.

The rest of the world will inevitably move to accept the coronavirus as a severe cold, deadly for a vulnerable sliver of the population, but otherwise something to put up with. The other gamble is that there’s no COVID-20 or 21. None of this is affordable twice in a short space of time.

Next to Greta Thunberg, perhaps no other figure has captured the imagination of global progressives quite like Jacinda Ardern, New Zealand’s young, glamorous Prime Minister, bound for a historic election victory.