Ivan Moscovich survived Nazis’ hatred then puzzled our world

A mechanical engineer, Ivan Moscovich invented drawing machines, founded a science museum and designed endless puzzles.

OBITUARY

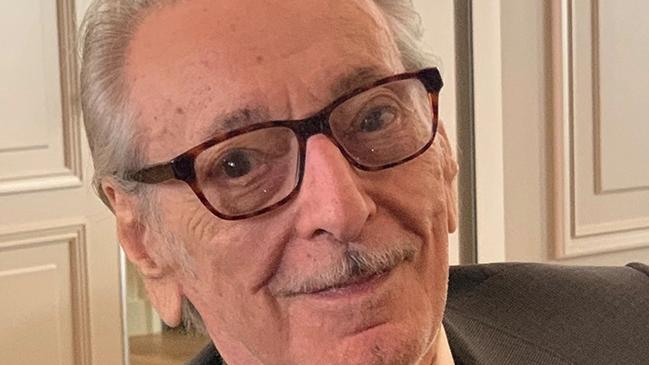

Ivan Moscovich Inventor.

Born Novi Sad, Serbia, June 14, 1926; died April 21, aged 96.

Ivan Moscovich’s story took in last century’s grimmest days: he was born in a country that no longer exists (Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes), spent the immediate post-war years in a country that also no longer exists (Yugoslavia) and then became a citizen of a country that did not exist until he was 21 (Israel).

By then he had survived the unique hatred unleashed across Europe starting in 1933 with Germany’s industrial-scale extermination of those who stood between it and a master race which, like Tolkien’s Ring, would “in the darkness bind them”.

But it didn’t. And men and women the Nazis considered unworthy of life went on to change our world – author Primo Levi, film director Roman Polanski, Otto Frank (Anne’s dad) and Nobel prize winners Elie Wiesel, Imre Kertesz, Roald Hoffman, Walter Kohn, George Charpak and Rita Levi-Montalcini. Then there was that indefatigable enemy of Nazism, Simon Wiesenthal.

A love for life brought them all through. Moscovich had that and corralled mathematics, science and art in ways that had not been seen to create a world in which he never again thought of that early horror. There was much to think about: his father – a painter and later photographer – fled to Yugoslavia after World War I, but was killed by the Hungarian army when they occupied its territories. In January 1942, Hungarian soldiers cruelly forced Serbs and Jews on to the frozen Danube, which they then shelled, shattering the ice with most of those on it drowning or dying from hypothermia.

Aged 17, Moscovich was sent with his grandparents and mother to Auschwitz. Once off the train his grandparents were sent to the crematoria to be murdered. Moscovich spent time in three more concentration camps and on two Nazi work gangs. At Auschwitz he had been tattooed with prisoner number 335544.

He and his mother defied the odds and survived. His last stop was the Bergen-Belsen camp where he was found by liberating British troops near death hidden on a hill of corpses. The Tommy who saw he was alive grabbed the camp’s German doctor and put a gun to his head: “If this man dies, you die, too.”

Years later a friend said he dreamt he won the lottery betting on his Auschwitz tattoo number. Moscovich went out and bought a lottery ticket – he was astonished to see it was numbered 335544. He didn’t hit the jackpot, but won his stake back.

He studied mechanical engineering at the University of Belgrade and migrated to the fledgling state of Israel where he worked as a research scientist developing teaching aids and educational games while endlessly working on puzzles. In the late 1950s he proposed a hands-on interactive museum of discovery. The Museum of Science and Technology opened in Tel Aviv in 1964. The following year, Frank Oppenheimer, who with older brother Julius, had worked on the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb, visited and returned to America vowing to match it.

San Francisco’s famous Exploratorium was opened in 1969, and included some of the installations Moscovich had built. Science museums have copied the formula worldwide.

By then Moscovich’s puzzles were popular across Israel and were being exported as his fame spread. He also developed and patented a geometric drawing apparatus called a harmonograph that using pendulums to push a pen into subtly deviant patterns in a manner not dissimilar to the Spirograph.

About that time, married American inventors Ruth and Elliot Handler unexpectedly dropped by Moscovich’s office and an impressed Ruth asked: “I would like our chaps in California to see your puzzles; are you ready to come over to California?” The Handlers founded and owned the Mattel toy empire and wanted to expand beyond its mainstay, the ever-popular Barbie and Ken dolls.

On arriving in California, he got to work on what would become the internationally popular Brain Drain card and quiz games; always challenging, they became increasingly complex while exploring maths precepts. He also developed the games 1000 Play Thinks, Visual Brainstorms and The Brain Power Decathlon, which promoted problem-solving analysis through origami-like pattern-making.

He spent the rest of his life in England and The Netherlands devising more than 5000 puzzles, and left behind another 10,000 A4 pages of them. Leading games-maker associations gave him lifetime achievement awards.

Some Holocaust survivors were overwhelmed by their memories. “I had the same symptoms,” he said four years back. “The difference is … my mind worked to save me. I needed the escape. The escape was a workaholic game inventor, which is what I became.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout