Its wings clipped, the last flight of the Concorde was a sorrowful affair

Two decades ago the supersonic, delta-winged masterpiece flew for the last time. Its short hop to a Bristol museum could not have been further from the jet’s brief golden age shuffling the newsworthy between London, New York and Paris.

The last flight of the Concorde was an inglorious affair – a feeble, low-speed, low-level 140km hop from London to Filton in Gloucestershire. It could not have been further from the supersonic passenger jet’s brief golden age shuttling the newsworthy between London, New York and Paris. Had Concorde a tail wing, it would have been between its broad delta feathers that day.

Concorde’s first flight was on March 2, 1969. Just 24 days earlier, the first Boeing 747 had taken off. Both seemed destined to usher in a new era in passenger aviation. One did. A total of 1574 Boeing 747s were made, a quarter are still registered and licensed to operate. The 747 revolutionised aviation, allowing more passengers affordable access to long-haul travel, and was especially significant for Australians. The jet set had, until then, comprised the northern hemisphere’s famous and powerful elite – and we read enviously about them. The 747 made us all jetsetters – and the last was built and delivered for service just this year.

Only 20 Concordes were made, six solely for testing. And while the other 14 sleek, delta-winged supermodels attracted dedicated followers willing to pay about $9500 one way for an Atlantic crossing, Concorde never flew profitably. Those last air miles to Filton took place 20 years ago this Sunday. By then Concorde had become a much-loved if expensive, loss-making marketing exercise for Air France and British Airways.

But the world had watched enthusiastically as Britain and France signed a treaty in November 1962 to build and operate the world’s first supersonic passenger jets. The Concorde countdown was long and laboured – eccentric even – mostly taking place at England’s legendary Farnborough Royal Aircraft Establishment and, arguably, starting with a now-forgotten disastrous, deadly balloon flight.

It is hard to believe that not much more than a century ago military aircraft were early balloons – even though the first work on jet engines began at the RAE in 1928. The balloons themselves were improvements on the so-called war kite. These were developed by American wild west showman Samuel Franklin Cody who travelled to Britain claiming to be the son of William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, but they weren’t related. His show was effectively a horseback shooting demonstration and it was popular.

In London, Cody encountered adventurous French balloonist Auguste Gaudron and became fascinated by the notion of manned flight. Soon Cody was building his own winged box kites and offered them to the British War Office for use in the Second Boer War – the idea being that ascending to 700m or so, an observer might safely scan the enemy lines, ranks, troop numbers and equipment.

By then, England’s Colonel James Templer had also made serious progress on balloons although his day job had been in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. He pretty much founded military ballooning at Woolwich in southeast London before moving to Farnborough.

But an episode early in the life of balloons turned out to be a significant setback. In an effort to prove the manoeuvrability of his balloon Templer set out to fly 75km from Bath in Somerset to Bridport in Dorset. On board his balloon named Saladin that evening were Templer, Walter Powell, a member of parliament, and a Mr A. Agg-Gardner, the brother of another MP. As they approached their destination, the wind picked up and they were headed towards the coast. They descended rapidly – with Templer calling out to a man on the ground, “How far to Bridport?” The man shouted that it was “about a mile”. Then they hit the ground hard with Templer and Agg-Gardner being ejected from the basket and Agg-Gardner breaking his leg. With their weight out, the balloon became unmanageable.

The Times reported: “The balloon here dragged for a few feet, and Captain Templer, who had been letting off the gas, rolled out of the car, still holding the valve line in his hand. This was the last chance of a safe escape for anybody … Mr Powell now remained as the sole occupant of the car. Captain Templer, who had still hold of the rope, shouted to Mr Powell to come down the line. This he attempted to do, but in a few seconds, and before he could commence his perilous descent, the line was torn out of Captain Templer’s hands.”

Powell and the balloon went out to sea roughly in the direction of France, never to be seen again.

Farnborough’s Balloon Factory was renamed the Royal Aircraft Factory in 1912, and its head designer was 30-year-old Geoffrey de Havilland, who would later develop a flexible but largely timber combat plane, the Mosquito, that performed as a tactical bomber and reconnaissance aircraft during World War II.

From 1912 until after World War I, de Havilland developed various aircraft at Farnborough and after leaving would work on the Vampire jet fighter. Jet engine technology had been on drawing boards in various countries for many years, but the theories were trumped by technical limitations. Investigating these was Alan Griffith who developed the idea of the jet engine at the RAE.

He wouldn’t see his plans come to fruition but his work on what we now know as metal fatigue is used to this day especially in the maintenance of modern passenger jets.

The breakthrough came from a weedy 152-cm tall, concave chested mathematics genius called Frank Whittle – twice rejected by the Royal Air Force – who had long ago worked out that propeller-driven aircraft could never reach the speed of sound, 1234.8km/h.

He is the father of the jet engine technology that has transformed the lives of those in the world able to afford to fly commercial aircraft. Indeed, it is hard to think of life without it, particularly for us in Australia. It was only in 1974 that more immigrants arrived here by plane than by ship. That year 377,535 people flew from Australia to another country. Last year it was more than 1.6 million. Thanks to the jet engine that took shape at Farnborough and ultimately would deliver Concorde.

Whittle worked on versions of the engine and patented it, but with little interest – and wary of the £5 cost – let it lapse. But Americans saw its promise and took over the technology and refined it.

We now take it for granted. Behind the scenes there was always the ambition that an aircraft might break the sound barrier – not as a gimmick like US Air Force pilot Chuck Yeager – but as a way to cross the globe with unmatched speed. This was especially important to those of us in the southern hemisphere so far away from the economic hubs of London and New York.

The effort to retake leadership in jet engine technology, and establish Farnborough as the world capital, fell to Arnold Hall, an aeronautical engineer who had worked there since 1938 and who, during World War II, had contributed to design modification of the legendary Supermarine Spitfire fighter planes, credited with winning the Battle of Britain in 1940. (Had the Beatles’ producer George Martin been asked, as he had hoped, to contribute a face to the cover of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band he was going to suggest Spitfire designer RJ Mitchell.)

Working with fellow aeronautical engineer Morien Morgan, Hall formed a committee in late 1953 to study the possibilities in commercial supersonic transport. Yeager had broken the sound barrier six years before. The committee thought any such aircraft design would involve huge aircraft that guzzled fuel uneconomically. A radical change was needed.

Two German-born RAE employees, aerodynamicist Dietrich Kuchemann and his collaborator Johanna Weber – still listed as “enemy aliens” at the time – produced a paper proposing a radical wing shape that distributed pressure and created vortices at its tip that would increase lift. Wind-tunnel modelling suggested it would work.

Morgan understood the ramifications for supersonic aircraft design and his work led to the planning for what was called the Bristol Type 223, the shape of which is familiar to anyone who ever saw Concorde.

Coincidentally, the French state-owned Sud Aviation had been working on a similar but more modest proposal known as the Super Caravelle which would have carried 70 passengers, but would not have had the range to cross the Atlantic. Later it emerged it was less a coincidence than the British thought; the Morgan team plans had been leaked to Sud.

The design, construction and testing of any such aircraft was an investment beyond that of most private companies and even state-owner national carriers. By 1962 it was estimated that development costs for the as-yet-unnamed supersonic passenger jet would be more than $6bn in today’s money.

The British government baulked at these costs even though the RAE team believed it had made strong economic arguments for the jet for which it forecast a market of perhaps 350 planes. But Britain had applied to join the European Economic Community and it was believed if it partnered with the French to build this aircraft it might promote its chances of membership. On November 9, 1962, the agreement was signed.

French president Charles de Gaulle, the following January 25, announced the project would be called Concorde – and also that he had vetoed Britain’s membership of the EEC.

A furious British prime minister Harold Macmillan, who had been injured fighting in France during World War I, immediately changed it to the English spelling, Concord. The “e” was eventually restored with the public being reassured it stood for “excellence, England and entente”.

Sales efforts started long before any Concorde ever flew, but the oil shocks of 1973 – Arab payback for the West’s support of Israel during the Yom Kippur War – and the stockmarket crash took the wind out of the global economy. Sales that were made, and options taken out, were cancelled.

Cost continued to grow almost exponentially, but Concorde was now an issue of national pride. And, by 1973, Britain was in the EEC. The industrial chaos in Britain meant that to conserve electricity industry was reduced to operating three days week – and television broadcasting ended at 10.30pm – but even in these almost Third World conditions, Concorde proceeded.

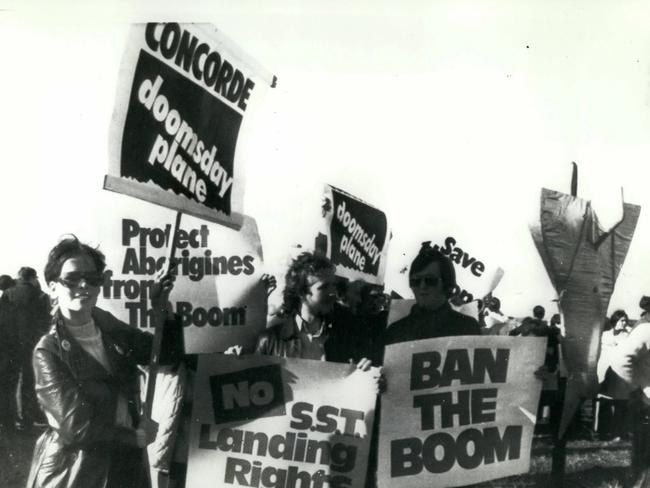

Following test flights throughout 1969, Concorde finally went supersonic, breaking the sound barrier on October 1 that year on a flight out of Toulouse. Of course, its sonic boom was to be a near fatal drawback. Concorde’s test models were pretty noisy to begin with, and many countries initially ruled it out from overflying their territory because of the sonic booms as it travelled either side of the sound barrier.

From Heathrow to Washington and New York, Concorde tracked west over England rising to 28,000 feet, then accelerating quickly to Mach 1.7 as it passed beyond Cardiff over the Bristol Chanel and rose to 43,000 feet. It would reach Mach 2 about 50,000 feet and, as the fuel burnt off, could rise to 59,000 feet. Friction caused the airframe to heat up and the plane stretched almost 23cm in flight. It would descend and go subsonic about 90km off the US east coast.

A unique feature was the nose cone that dipped 5 degrees as they prepared to land to give the pilot and first officer a better view of the runway, which they would approach at about 150 knots.

Captain John Hutchinson, who flew Concorde from 1977 to 1992, said it was relatively easy to operate – “You could fly it with you thumb and forefinger” – although pilots had to get used to sitting more than 10m in front of the nose wheel.

He described it as “very powerful, very responsive, a very beautiful thoroughbred of an aeroplane”.

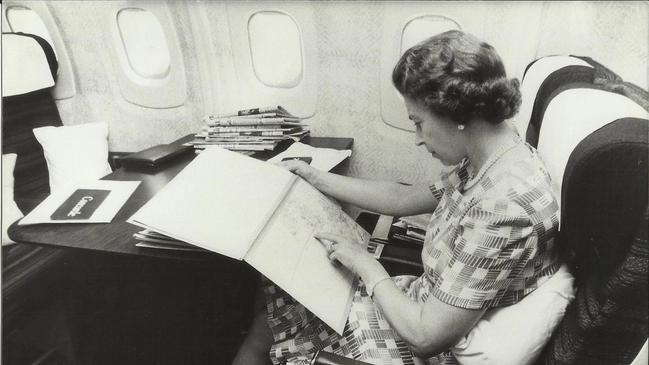

Fascinated locals – warned by hostile authorities about the noise of Concorde – gathered in their tens of thousands for its inaugural arrival at Washington’s Dulles International Airport. And Concorde was a hit wherever it went, including several visits to Australia.

The smokey prototype arrived noisily on a demonstration flight via Darwin to Sydney and on to Melbourne at the end of May, 1972, greeted by 20,000 fans and a few protesters. It had flown supersonic over parts of the Northern Territory and South Australia with Australian technicians recording it all along the supersonic corridor. One newspaper sent its own correspondents to listen in to the famous booms: “Some said they heard nothing. Others said livestock and fauna were not disturbed.”

The improved and quieter Concorde returned in 1975 and 1985 and finally in 1994.

It had originally been hoped there would be three flights to Australia each week. They would have involved 10 hours of flying, but refuelling stops every 7000km would stretch the trip out to 13 hours. In 1989, a specially adapted 747-438 flew non-stop from Sydney to London in 20 hours.

The great attraction of Concorde was its flight time between London and New York, which it once completed in 2 hours, 52 minutes and 59 seconds.

Hutchinson recalled that passengers would often tell him “I wish it could have been longer, I was enjoying it that much”, with no irony at all.

Arsenal fan killed fleet

Concorde struggled after its first fatal accident but it took a civil engineer who admired Charles de Gaulle and was an Arsenal fan to kill it off.

At 4.42pm on Tuesday, July 25, 2000, an Air France Concorde took off from Charles de Gaulle Airport striking a 43cm-long piece of engine cowling that had fallen from a Continental DC-10 jet that had lifted off four minutes before. This shredded a tyre that broke apart, a chunk of it smashing into the underwing and causing a fuel leak that caught fire. The tower radioed the pilot informing him but he was at the point of no return. He’d have to take this problem into the air and try to sort things out.

The damage to the airframe was already so great, the plane could not gain elevation. It never rose above 60m. It crashed into a nearby hotel, killing 100 mostly German passengers on their way to rendezvous with a cruise out of New York, nine crew and four people on the ground. The French and British Concorde fleets were grounded.

When investigators worked out what had happened the aircraft’s tyres were changed and its underwing area modified. What happened to Flight 4590 could never occur again. A suitably adjusted British Airways Concorde completed a test flight on July 17, 2001, to Iceland and back, mimicking a run to New York. It went seamlessly, with crowds at each end welcoming Concorde’s return.

The first flight with passengers took off from London and headed to New York on September 11 that year, arriving just before the attacks on the World Trade Centre. Osama bin Laden would not have known that 40 of the most regular Concorde travellers – between them making 800 supersonic flights each year – worked there and were killed.

Confidence in air travel plunged. Bin Laden, the son of a Saudi billionaire, had studied civil engineering and English not far from Heathrow while enjoying Saturday afternoons at Arsenal’s Highbury ground. Its new ground opened 15 years ago bearing the name Emirates Stadium.

With the costs of sometimes nearly empty flights mounting, British Airways retired its Concorde fleet on October 24, 2003.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout