It’s not perfect, but we all win from welcome to country

Quibbles over the format of the ceremonies are irrelevant compared with what we gain.

Like many Australians I have sat through some pretty ordinary versions of welcome to country over the years. Some were poorly delivered, some far too long, some sentimental and some positively aggressive.

How many times, sitting in a corporate conference, a concert or at a fundraising dinner have I winced at the attacks on white Australia? How often have I felt embarrassed by an exercise that can sometimes be clumsy?

How often have I wondered after a particularly poor rendition whether some Indigenous Australians need a lesson in communication?

How often have I worried that an opportunity to educate white Australia has become a display of ego – and yes, resentment – instead?

At times organising a welcome to country has been frustrating. How is it that an institution cannot choose who gives the welcome but must trust a third party to select someone who understands the audience and shapes a welcome accordingly? We understand that as non-Indigenous Australians, we cannot control the welcome, that this is an Indigenous gift to us. We know the elders and traditional owners deserve to be remunerated, but why, we have sometimes wondered, are we paying them to harangue us?

Yet for every bad hair day, there have been memorable welcomes that move us to tears, lift our hearts, remind us of the resilience and generosity of First Nations people – and, most important, remind us of our history, the one that goes back 65,000 years, the one that’s easy to forget as we speed through lives largely disengaged from country or land or the bush.

Last week as I stood on the ancient land of Mungo National Park in far western NSW, I was reminded again of the immense legacy we are invited to share in these welcomes. It’s hard to get your head around the deep past but it made more sense out there, where our Indigenous guide gently welcomed our bunch of Australian, Japanese and other tourists to his country. It wasn’t an official welcome but we murmured thank you. And meant it. Not so much a spiritual experience for me but a privilege to be at one of the world’s most significant archaeological sites, guided by a man whose ancestors lived and died on this spot.

That’s why, despite the view of people such as Tony Abbott that it’s time to dial back welcome to country, I reckon non-Indigenous Australians still win enormously from this ceremony.

In August last year, at the height of the debate on the voice, the former prime minister declared he was “sick of the welcome to country”.

The country, he said, “belongs to all of us, not just some of us”. Abbott went on to question the Aboriginal flag: “I’m getting a little bit tired of seeing the flag of some of us flown equally with the flag of all of us.”

The much-loved Aboriginal flag is pretty safe, but welcomes may be contested now that the No vote in the voice referendum has given Australians “permission” to challenge policies and protocols.

Abbott’s allusion to ownership of the country carries dangers for Indigenous Australians and those who value the welcome because it raises, incorrectly, fears that the ceremony is about Blak sovereignty rather than respect for traditional lands.

Wikipedia says the welcome is about “ highlighting the cultural significance of the surrounding area to the descendants of a particular Aboriginal clan or language group who were recognised as the original human inhabitants of the area … it serves also as a symbol which signifies the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ presence in Australia before colonisation and an end to their past exclusion from Australian history and society, aiding reconciliation with Australia’s First Nations.”

The ceremonies began in modern Australia 50 years ago when one was performed at a festival at Nimbin in the Northern Rivers region of NSW. But it was a slow start: the second ceremony was in 1976 when entertainers Ernie Dingo and Richard Walley organised a welcome for Maori artists at the Perth Festival.

“Walley recalled that Maori performers were uncomfortable performing their cultural act without having been acknowledged or welcomed by the people of the land,” Wikipedia notes.

It took until the 1990s and the Mabo judgment for Australians to begin acknowledging the traditional land and its custodians, spurred on too by the reconciliation movement.

Welcomes, which should be performed by local elders or traditional owners, became more common but were given status in 2008 when they were introduced for the opening of federal parliament after each election.

The ceremony quickly became part of most public events, often with music, dance and smoking ceremonies added. The words chosen for some welcomes have become more pointed as Indigenous people seek constitutional recognition and “always was, always will be Aboriginal land” has become a regular statement of support by both black and white Australians.

Acknowledgments from white Australians are important but risk becoming meaningless through overuse. Must every speaker at a conference acknowledge the land? Might a welcome and an opening acknowledgment from the chair suffice?

But quibbles over the style or number of these efforts at Indigenous recognition are irrelevant compared with what we gain as a nation from welcomes and acknowledgments.

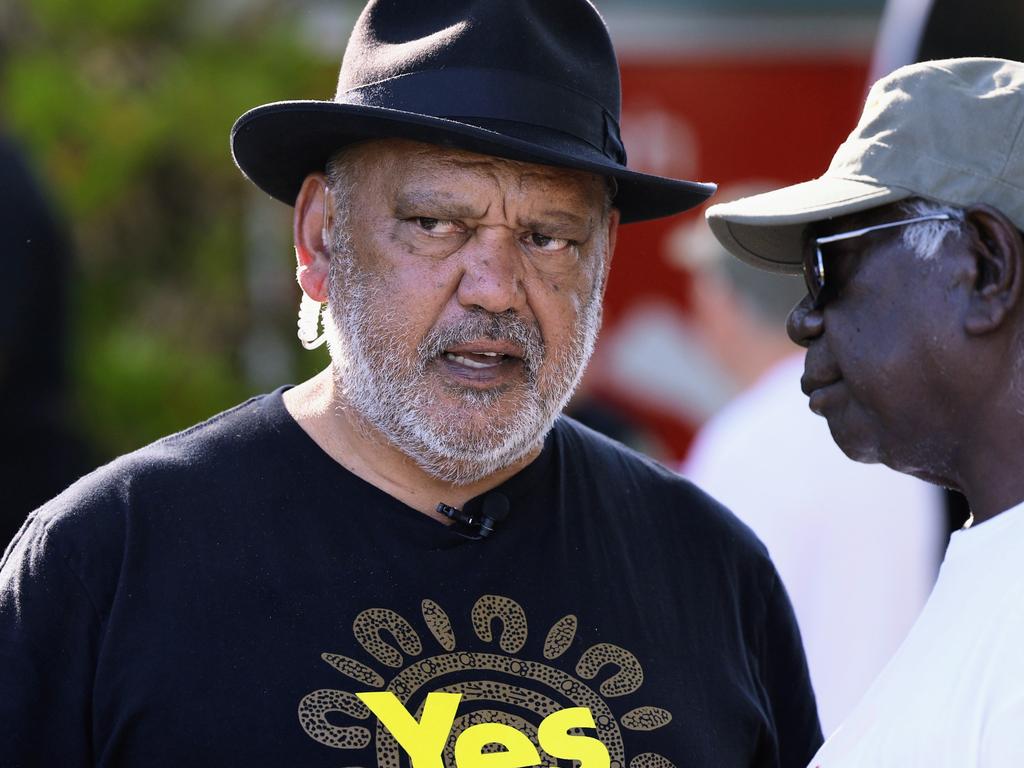

Last year when I interviewed University of Melbourne professor Marcia Langton for The Weekend Australian Magazine, she said: “I imagine that most Australians who are non-Indigenous, if we lose the referendum, will not be able to look me in the eye.

“ How are they going to ever ask an Indigenous person, a traditional owner, for a welcome to country? How are they ever going to be able to ask me to come and speak at their conference? If they have the temerity to do it, of course the answer is going to be no.”

Online, the story provoked more than 4500 comments from readers, many of whom indicated they would welcome the end of the welcome.

Langton’s deeper message about the importance of the voice and the welcome to Indigenous Australians was largely lost.

Over the next few months we will see if organisations dial back the ceremony and if elders decline to deliver. Let us hope not.

The welcomes help us come to terms with our history and need support as they continue to evolve in a post-referendum world.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout