It all ads up to your vote

Vast millions are being spent on political advertising this election campaign in search of that winning edge.

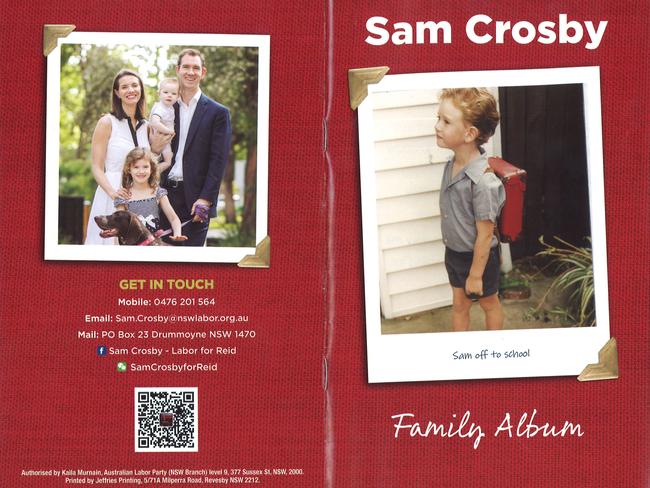

In Sydney’s key battleground seat of Reid, in the city’s west, voters have received a mock “family album” from Labor candidate Sam Crosby, a former political staff member.

It’s an example of the way political messages are being tailored to individual electorates. There’s Crosby starting school with a little red backpack; there he is on his wedding day; and lovingly wrapping newborn daughter Charlotte in a hospital blanket.

There’s no mention of any professional qualifications for the job, but the message is clear to a relatively conservative electorate: here is a man who grew up in your area, is just like you and shares your values.

Under the radar, Crosby — son of a former union leader and married to a NSW Labor upper house MP — is also running a slick Chinese-language campaign. More than half of Reid, which the Liberals hold with a 4.7 per cent margin, speak a language other than English at home.

He has an active presence on Chinese social media site WeChat and a Chinese-language website. There’s little Charlotte again — this time wishing voters a happy Chinese New Year in Mandarin.

It’s a tough match for child psychologist Fiona Martin, who is trying to hold the marginal Liberal seat but starting on the back foot. Martin was preselected only last month after key Malcolm Turnbull backer Craig Laundy quit, and her party fears she is headed for defeat. One of Martin’s first moves was to join WeChat.

A senior Labor figure says the pivotal role of WeChat in battleground electorates with significant Chinese populations — including Chisholm in Melbourne’s east, Banks in Sydney’s south and Moreton in Brisbane’s south — is one of the biggest changes this election.

Labor has used it well, building followers through live chats and co-ordinated messaging. But the party says it has been burnt by “remarkable lies” — about death taxes and an increase to Middle Eastern migration — that have been hard to shut down.

“It’s like the home of fake news,” the Labor source says.

Truth seems to be optional for all players in this campaign — there are no federal political advertising laws to prevent them telling porkies.

Travelling north to Herbert, the nation’s most marginal seat, covering most of Townsville, voters are being bombarded on social media with an LNP ad featuring Labor MP Cathy O’Toole trying to dodge questions on her support for the Adani coalmine. O’Toole won the seat by just 37 votes in 2016. Labor’s advertisements, on the other hand, attack the LNP’s “desperate” preference deals that place Clive Palmer before Townsville workers.

Social media was important in 2016, but this time there’s a new level of sophistication. Parties can target their ads by postcode, age, views on an issue — even fondness for a specific car brand. According to a series of near-identical Liberal party ads, Bill Shorten wants to tax your Ford Ranger; your Toyota HiLux; your Mitsubishi Triton.

Similarly, Queensland Labor is telling voters in various locations the Coalition has cut funding to Caboolture Hospital; the QEII Hospital, the Prince Charles Hospital; Redcliffe Hospital; Logan Hospital; Townsville Hospital; and others. The claims on both sides are questionable — in our post-truth world — but research suggests voters care most deeply about issues that are local.

Parties need to be more engaging online because voters can skip over the boring stuff and the algorithms punish poor content.

“On TV a bad ad will work if there’s a big enough spend,” one advertising executive explains.

Political operatives can get instant feedback about what is working and what isn’t, and can respond almost instantly to an event of the day.

A Liberal figure says this week, after the debate between Josh Frydenberg and opposition Treasury spokesman Chris Bowen finished at the National Press Club, the party was ready to deploy its messages online within 30 minutes.

There is no inspiring “It’s time” slogan but the ads on both sides have been well produced and engaging. The Liberal Party is using Adelaide-based creative agency KWP and international media buyer Starcom for its campaign, backed by an army of hardworking staff at its campaign headquarters in Brisbane.

Labor is using Darren Moss as its creative director, the architect of “Mediscare” — and a similar battalion of staff slogging at its headquarters in western Sydney.

Senior figures in the Liberal Party believe their message of “The Bill you can’t afford” is cutting through. It is being sold in different ways. Labor leader Bill Shorten is depicted as Pinocchio (lying about new taxes, and a union puppet to boot); on a carousel (“every time Bill comes around he’s got a new tax”); and in his running gear (sprinting from questions about higher taxes). Another ad features family photos in a vice: Labor’s higher taxes “will put the squeeze” on all Australians.

On the Labor side, the message that it’s time to “end the cuts and chaos” is also resonating, according to internal party research. It has ads that feature Scott Morrison with Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton and former prime minister Tony Abbott over his shoulder; they warn the Coalition is slashing billions from schools and hospitals because it is “only for the top end of town”.

In the recent NSW campaign, the party deployed similar ads, featuring Premier Gladys Berejiklian with the Prime Minister, Abbott and Dutton behind her. The party obviously is recycling the imagery because it believes it cuts through.

Labor’s message of envy — that nurses and other “ordinary people” are forced to wear cuts while billionaires get tax relief — echoes successful ads run in Britain by Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn.

Both major parties are fighting this election with healthier war chests than in 2016 and their spending on advertising reflects this. So far the Liberal and Labor parties have forked out $8.8 million and $9m respectively.

For all the social media sophistication, senior players on both sides agree it’s the traditional media that still counts — particularly television. “There is still no substitute for heavy, negative pounding during making-your-dinner time,” says a senior Labor figure.

The Liberal Party — burnt last campaign when it was too slow to react to Labor’s “Mediscare” campaign — has no qualms this time about going negative.

Liberal strategist Grahame Morris says there has been about one positive ad for every three negative, which is “probably normal”. He says both sides have known for more than 40 years “the power of negatives”, but then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull “decided he knew better”. Morris says without a powerful counter to the Mediscare campaign — which heightened fears of cuts to the health system under the Coalition — the party lost 10 seats.

“That campaign was a one-off and will never happen again,” Morris says.

The complication for all parties is that more and more voters are heading to pre-polling booths. Almost one in three cast their ballot before election day in 2016, and this year the figures so far suggest the total could be even higher.

More than 1.15 million have already cast their vote, according to the most recent Australian Electoral Commission figures — so relying on a massive blitz of ads in the final week of the campaign may be too late.

One man who decided to start blitzing the airwaves early is Palmer. His intervention in the campaign is unprecedented in Australian politics, according to Australian National University marketing lecturer Andrew Hughes. So far, Palmer has spent $39.1m on advertising since September, according to data and analytics group Nielsen — more than both major parties combined — and he has suggested the figure could reach $60m by election day.

His face is beaming from bright yellow billboards in every electorate in the country, other than the Northern Territory and ACT, where such political advertising is limited. From well-heeled inner-city seats such as Wentworth in Sydney and Kooyong in Melbourne, to far-flung seats such as Leichhardt in Queensland’s far north and Durack in Western Australia, he is promising — in echoes of Donald Trump — to “Make Australia Great”.

Palmer is also relentless in 15-second ads on TV and on the most popular breakfast radio slots, and he has nabbed prominent print-media real estate. His ads are clever and catchy. “Australia ain’t gonna cop it” is another message ripped from the US — from metal band Twisted Sister’s hit We’re Not Gonna Take It — at least according to Universal Music, which is suing Palmer for breach of copyright in the Federal Court.

The latest Newspoll published in The Australian this week showed Palmer’s support nationwide dipped slightly to 4 per cent, down from 5 per cent the previous week. But in individual electorates his support is much higher, and pundits expect his $50m or $60m spend will buy him his coveted Senate seat in Queensland.

The ABC’s Antony Green says it is impossible to predict whether Palmer will also pick up a Senate seat in NSW or elsewhere. His general rule of thumb is that a party needs about 7 per cent of the vote to pick up a Senate seat.

Other groups have intervened in this campaign, some in questionable ways. The unions and GetUp have played a prominent role, while the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners angered some doctors by controversially plugging the message our health system is becoming Americanised, and Australians are missing out on seeing a GP because they can’t afford it. Because who needs the truth?

Only one thing is certain — you can expect those airwaves to be pounded until the media blackout hits on Wednesday night, and for social media messages to ramp up until election day. Then we can figure out which ads really worked.