Trump has imposed 145 per cent tariffs on all exports from China to the US. Estimates are that this could slow China’s GDP growth by 2.5 per cent. Beijing has responded with tariffs of 125 per cent against the US.

Tariffs aren’t bombs but they are weapons.

Trump is determined to remake global trade, to remake America’s alliances, to transform America’s standing in the world, to change America in its domestic character, to “make America great again”.

Historian Niall Ferguson argues instead that Trump has brought about the end of the American empire, with potentially devastating consequences. There’s a deeper question: has Trump deprived the world of the America that has been the sole principle of order since 1942? No question could be more important than this for Australia.

Trump’s past fortnight has been chaotic and destructive. His administration has been at war with itself. Trump’s new best friend, Tesla boss Elon Musk, whom Trump entrusted to remake government, called trade adviser Peter Navarro “a moron”. Navarro, author of the tariffs, claimed Musk was just a car manufacturer.

On “Liberation Day”, April 2, Trump announced tariffs on almost every nation and territory in the world. The list was so slapdash, put together in such an amateur and cack-handed fashion, it included territories with no inhabitants, apparently because at some point a shipment of some goods to the US was wrongly attributed to them.

It was probably compiled using artificial intelligence, with tariff formulas mechanically constructed from the size of any relevant US trade deficit. A 10 per cent general tariff applied everywhere.

No country got an exception. Australia’s ambassador, Kevin Rudd, had convinced Trump’s economic advisers to exempt Australia, given the large trade surplus the US enjoys with us and our status as a close ally, plus the potential for US access to Australian rare earths. Trump administration hard-liners nixed the deal. China has stopped supplying rare earths to the US.

The stockmarket reaction to Trump’s tariffs was overwhelming. US stocks lost more than $US5 trillion ($8 trillion) in value. Millions of Americans lost a big chunk of their retirement savings, typically invested in stocks. Australians’ super funds are also heavily exposed to US stocks.

Until Liberation Day, America had a strong reputation as a safe place to invest.

There was talk Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent threatened, or at least hinted at, resignation if Trump didn’t reverse course. Trump himself declared on social media platform his policies “WILL NEVER CHANGE”.

The force that beat Trump, persuading him to suspend punitive tariffs for 90 days, was more powerful than Bessent or Beijing. It was the bond markets. They ganged up on Trump as they once ganged up on the short-lived British prime ministership of Liz Truss.

The US 10-year Treasury bond has been the safest investment of all. But the bond rates climbed dramatically. People were reluctant to lend even to the US government. The US has a budget deficit of nearly $US2 trillion and government debt of some $US36 trillion. The US Senate had amended a House of Representatives budget resolution effectively to abolish house-authored budget savings, while extending tax cuts and new spending. At week’s end the house accepted the Senate amendments. Fiscal discipline took another pass.

The budget mess, in combination with the tariff chaos, made the bond markets skittish, threatening a full-blown financial crisis.

So Trump suspended the individual country tariffs while keeping the 10 per cent general tariff. Beijing had already retaliated against Trump’s 34 per cent tariff on China. So Trump retaliated against the retaliation. China did the same. We ended up with today’s stand-off.

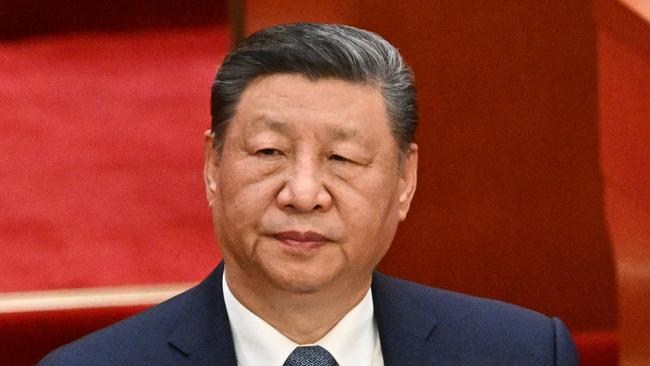

Trump continually invites his counterpart, Xi Jinping, whom he describes as “very intelligent” and someone he knows well, to make a deal.

It may be that Trump has blundered into a potentially sustainable situation. The White House reports that 75 nations have approached it to make trade deals. Trump immensely enjoys being the centre of world attention and the object of supplication from lesser national leaders.

With his characteristic grace and presidential dignity, Trump remarked that leaders were “kissing my ass”.

Although Trump remains unpredictable, it’s unlikely that after 90 days he’ll reinstate global tariff madness. He was genuinely scared of what he’d unleashed. Otherwise he wouldn’t have reversed himself. This willingness to instantly abandon a strongly held position is, peculiarly, a strength of Trump’s.

Now we await the Washington-Beijing battle of wills. Some kind of short-term deal must be likely, though neither side wants to look weak. But a short-term deal is not a grand bargain.

The US and China are locked in a grave, epic struggle to dominate the world in the years ahead. Matt Pottinger, deputy national security adviser in Trump’s first administration, argued this week: “China’s economic model is designed as a means to political, not just economic, dominance around the globe.”

In an important new piece in Foreign Affairs, former deputy secretary of state Kurt Campbell (the most hawkish figure on China in Joe Biden’s administration) argues that Americans, having once overestimated Beijing, are now seriously underestimating it.

China is the top trading partner for 120 countries. It has the biggest navy in the world. In some areas of hi-tech, and even military tech, it’s ahead of the US.

Trump occasionally talks about the big beautiful oceans that separate America from the world’s worst conflict zones. Campbell: “By retreating to a sphere of influence in the Western hemisphere, the US would cede the rest of the world to a globally engaged China.”

The US has never faced a strategic competitor as formidable as China. Its key advantage over the US, Campbell argues, is mass, even as it remains a smaller economy than the US.

There is a ready-made way, but only one way, the US can acquire the mass to more than match China. That’s through a much greater military, industrial and technological integration with its allies. Beijing itself has long recognised the US alliance system as one of America’s greatest strengths.

Beijing at last has been able to build its own formidable quasi alliance system with Russia, Iran and North Korea.

This is one reason Trump’s tariff moves have been so disastrous. Until the 90-day suspension they made not the slightest distinction between America’s closes allies and longstanding adversaries.

Allies were aghast at the instability Trump caused. No global business could plan rationally for the future.

Mike Green, head of the US Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, and author of the definitive history of US policy in Asia, thinks Trump has done the greatest harm to America’s reputation, especially among allies, since the Iraq invasion and perhaps since the failure of the Vietnam war.

Green remains, nonetheless, a long-term optimist. He doesn’t think Trumpism will be powerful once Trump is gone. He says the US default position in Asia is not isolationism but engagement, to protect its interests and prevent dominance by a regional hegemon. He also thinks, apart from Trump, the US is a natural sell in Asia because the alternative is the Chinese Communist Party.

The US is also, historically, dynamic in its comebacks. Says Green: “The US has a history of diplomatic self-harm, and relatively rapid recovery.”

Economist Chris Richardson outlines the straightforward imbalance between the world’s two biggest economies: “The US spends more than it earns, while China earns more than it spends.”

The single best thing the US could do to fix its $US1 trillion global trade deficit would be to eliminate its budget deficit.

Every year the US pumps huge extra demand into its economy through its huge budget deficit of nearly $US2 trillion. But US politics, as the recent budget resolution shows, can’t bring itself to balance its budget.

China, which has moved to a quasi war economy, and put more emphasis than ever on making as many things as possible domestically, is unwilling to move towards a consumption economy, with a higher standard of living.

Trump is right in arguing that many aspects of the international trade system are unfair to the US. Both the EU and some Asian nations make it harder for the US to sell products into their markets than vice-versa. But Trump conflates this with every other real and imagined grievance he thinks America suffers. He’s right to castigate allies for free-riding on American security. No nation is more guilty of this than Australia.

But Trump wildly exaggerates the disadvantages he believes America endures.

It has the highest per capita income in the world, at $US83,000. It still accounts, on International Monetary Fund figures, for a staggering 27 per cent of the global economy. It enjoys effective full employment. If Britain, France and Germany joined the US they would be, per capita, the poorest states in the union.

Trump’s complaints about China are much more substantial. Pottinger points to Beijing’s theft of intellectual property, forced technology transfers from Western companies operating in China, market access barriers and massive industrial subsidies as reasons for its huge trade surplus. Campbell argues that Beijing subsidises its companies to sell at a loss to establish market dominance, especially in strategic industries.

If the US-China trade war continues, China will dump cheap excess product in many other countries. Australia should be aware of this. If China is selling stuff cheap we don’t make, we could take advantage of the low prices. But if it threatens any Australian industry, we should stop such sales.

Trump made a trade deal with China in his first term as president, but Beijing didn’t honour the deal. Trump boasted China would buy hundreds of billions of dollars more US exports than ever before. It didn’t happen.

China massively subsidises credit for selected companies in strategic fields. This is every bit as protectionist as high tariffs but insidious because it’s less visible.

On top of that, Trump has never forgiven China for Covid, which Trump believes cost him re-election. There’s a deep bipartisan consensus in the US that China is its chief strategic competitor and that Washington must win the competition. But does Trump even think in those long-run geostrategic terms?

His administration so far is deeply divided and extremely sloppy, from holding sensitive security dialogues on the Signal app to announcing tariffs on uninhabited islands. When asked what factors made him change his mind and suspend his earlier global tariffs, Trump replied “instinct”, and that the decisions he would make on tariffs in the future would be “mostly instinctive”. That’s madness. It’s as near to the divine right of kings as any modern democratic ruler has ever claimed.

Trump’s objectives also appear hopelessly confused. Sometimes he talks of tariffs as a temporary means to get a level playing field for America. At other times he markets them as an ongoing and fundamental source of revenue.

Some analysts think Trump wants to keep the 10 per cent base tariff as a permanent revenue stream while negotiating the other stuff away. The 10 per cent tariff might furnish $US300bn or even $US400bn a year. Often, Trump markets tariffs as helping to re-industrialise America. But to have that effect they would need to be substantial and permanent.

But can anyone believe any deal with Trump is permanent? In his first term Trump negotiated a trade deal with Canada and Mexico that he described in glowing terms. Within weeks of coming to office this time he levied punishing tariffs on his two close neighbours. Where can Trump point to anything stable he has established?

The stakes for Australia are enormous. The US provides four essential goods to the world, all of which we need. One is security guarantees, especially extended nuclear deterrence, so that nations such as Australia don’t have nuclear weapons of our own but other nuclear powers are deterred by our nuclear ally, the US. Trump has called these commitments into the deepest question by constantly trash-talking NATO and saying there are numerous NATO members he wouldn’t defend.

The second great public good the US provides is access to its vast domestic market. The US used to provide this access strategically, and somewhat selectively, to help allies in the developing world become stable democracies. The whole east Asian economic and social miracle was based on this. But in Trump’s tariff mania some of the poorest countries, with the least capacity to buy American exports, were to be hit the hardest.

The third good is stability. The US provides political stability. Trump doesn’t do stability.

And finally, America provided moral leadership. Much more than the UN secretary-general, the US president was traditionally the secular pope, the leader of the free world. His words had great power.

Recall John F. Kennedy: “The United States will bear any burden, support any friend, oppose any foe, to ensure the survival of liberty.” Recall Ronald Reagan in the divided city of Berlin: “Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” When the devastating tsunami hit Indonesia in 2004, the US and Australian navies were there to provide critical help before anyone else. Trump doesn’t do moral leadership.

Modern Australia began as a British colony in 1788 and defined itself, quite naturally, as British, effectively independent, but British, for 154 years, until 1942. For the 83 years since 1942, our orientation has been American. First the British, then the Americans, provided our security (and much cultural inspiration), though we also fought heroically in our own interests and in wider alliance interests.

Trump is certainly a mixed grill. The question is: under Trump, do we lose forever the America we’ve always loved and relied on, been inspired by? Does Trump’s America play the security, economic and moral leadership roles we so badly need from America? Or does Trump embody only the principle of chaos?

I don’t know the answer to those questions.

Donald Trump has taken the most aggressive actions against China of any US president since Harry Truman was urged by General Douglas MacArthur to use nuclear weapons on China in the Korean war.