Is the US still Australia’s best bet, or will AUKUS make us a target?

Is the US an indispensable power we must continue to look towards, or is Australia materially eroding its security for no gain?

Is the US an indispensable power we must look to, or is Australia materially eroding its security for no gain? Michael J. Green and Sam Roggeveen delve into the opposing arguments surrounding AUKUS and the US alliance.

-

America is still Australia’s best bet

Michael J. Green

America’s leaders have found different ways to emphasise that a world absent US leadership is a world its friends and allies would not want to see.

Former secretary of state Madeleine Albright, whose Czech family had survived Hitler’s Reich and Stalin’s Soviet bloc, passionately called the US “the indispensable nation”. President Joe Biden likes to say nobody has ever won by betting against America.

Perhaps the most memorable example was that of former British foreign secretary Lord Carrington, who reportedly responded to his European counterparts’ litany of complaints about the Reagan administration in the 1980s by acknowledging, “Yes … yes … everything you say about the Americans is true … but they’re the only Americans we have.”

For US allies, of course, history has not been free of friction or anxiety about America’s choices. When ANZUS was signed in 1951, the Pentagon rejected initial Australian requests for a greater concentration of US military power Down Under and focused on Japan and Korea instead. In the early 1960s, prime minister Robert Menzies argued with president Lyndon Johnson that US intervention was necessary to stop communism in Southeast Asia, and a decade later Gough Whitlam and Richard Nixon fought with what historian James Curran calls “unholy fury” about American overcommitment in Vietnam.

Nixon’s subsequent withdrawal from Southeast Asia under the Guam Doctrine and Jimmy Carter’s attack on Asian allies over human rights rattled US partners, even prompting Seoul to begin a clandestine nuclear weapons program. In the ’80s, the US alliance with New Zealand broke over nuclear ship visits, while Americans told pollsters they saw Japan’s economy as a greater threat than Soviet nuclear weapons.

When the Clinton administration came into office, cutting defence spending and picking trade and human rights fights with China, Japan and Southeast Asia, prominent Japanese journalist Yoichi Funabashi warned in the American version of Foreign Affairs that American leadership was over and the next century would bring the “Asianisation of Asia”. This was not the first or last such prediction. There has not been a decade since 1945 when editorials somewhere in Asia did not raise alarm about American reliability and staying power.

With the Trump presidency, the January 6, 2021, storming of the US Capitol and relentless stories about gun violence and political polarisation, these doubts are back in the public discourse. Biden’s 2020 election victory and the defeat of election-denying extremist candidates in last year’s midterms helped to restore confidence in American democracy and internationalism, but the subsequent fights over Kevin McCarthy’s speakership and the national debt – and yet more stories of gun violence – suggest continued ills. And just as Soviet military expansionism or Japanese economic hyperpower seemed to amplify the weaknesses in American society in previous decades, today China looms large.

While the debate about the US can and should continue, the question for Australia (and other allies) is not whether to abandon America – a choice rejected in polls and bipartisan policies. The critical question is what kind of America Australia needs – and what Canberra can do with other like-minded states to shape US strategy in ways that underpin Australian sovereignty and security.

Competing with China

The Biden administration’s 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy is the most coherent framework Washington has yet produced on the region and enjoys strong bipartisan support. That strategy argues that instead of attempting to shape Beijing’s choices through direct engagement, the US should prioritise shaping the region around China to blunt growing Chinese coercion and mercantilism. And it depends entirely on US allies and partners.

Indeed, this strategy is the greatest American investment in alliances since at least the ’80s. Through the AUKUS agreement, the US has committed to transfer one of the crown jewels of American military technology – nuclear propulsion – to Australia.

The Biden administration also racked up a major success with allies when it reached agreement with Japan and The Netherlands in January this year to deny China access to the most advanced semiconductor fabrication technologies. This coalition responded to Beijing’s ambitions to dominate artificial intelligence by ensuring that the democracies retain their lead in semiconductor production.

This is not mere rent-seeking mercantilism: AI eventually will shape everything from the battlefield to personal liberties. Multiple governments now agree that Xi Jinping’s China – in which decreasing political freedom at home is coupled with “wolf warrior” diplomacy overseas – must not be allowed to dominate the information technologies of the future.

While policy debates in Washington are always ugly up close, the Biden administration, despite the polarisation, has demonstrated the kind of strategic competence that allowed previous American governments to preserve a favourable regional order in the face of hegemonic challengers.

China is a bigger challenge than Japan or the Soviet Union were last century, but it also has big internal problems. Xi is presiding over a government that is suppressing innovation and the private sector, encouraging technology decoupling by other economies with his strategies such as “dual circulation”, and provoking antagonism with aggressive policies in every direction except towards Russia. The birthrate in China has halved across the past five years – something demographers see only during times of catastrophe, such as the Great Leap Forward or a world war – indicating that not everything is right with the Chinese people. Few economists still predict that China will surpass the US to become the top economy by the 2030s. This internal uncertainty and weakness should make us wary of projections of a straight upward trajectory of Chinese power.

Hamilton theory of American dysfunction

The most visible manifestation of trouble in the US in recent times has probably been Donald Trump and Trumpism. Trump’s version of populism, nativism and quasi-authoritarianism reflects a phenomenon that, for the most part, has spared Australia while sweeping over democracies in much of the rest of the globe.

In the US this populism, matched at times by extremism on the far left, has collected in tide pools created by gerrymandered congressional districts and the profitable “anger-tainment” of cable television. As scholars such as EJ Dionne have pointed out, these tide pools would not exist if the US, like Australia, had compulsory voting, which would force candidates to play for support in the middle. For now, Americans are unlikely to embrace compulsory voting – though some states are instituting the next best solution, rank preference voting.

Meanwhile, as McCarthy found when he was struggling to get votes as Speaker of the US House of Representatives, there will continue to be safe spaces for politicians running on populism over principle, publicity over policy and nihilistic destruction over consensus and national interest.

But is this a trend? Anyone who has watched the musical Hamilton knows that muckraking, character assassination and polarisation have been features of American politics since Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson clashed in George Washington’s first cabinet meeting. Moreover, last year’s midterm election was a repudiation of election-denying extremism in every race other than JD Vance’s Senate election in Ohio, though the hedge fund executive turned Trump supporter significantly underperformed other Republicans in his home state. Trump’s star is nowhere near as bright as it once was, with most Americans saying they do not want him to run in next year’s election, former allies declaring he is unelectable and numerous lawsuits under way against him.

Many Australians were appalled at the US Supreme Court’s recent decision to overturn the constitutional right to abortion or the inability of congress to pass effective gun control legislation in the wake of mass shootings. Polls show most Americans agree. But the larger American experiment to create “a more perfect union” has achieved changes in politics and society that would have stunned earlier generations. By way of perspective, Americans in polls are far likelier than Australians to eschew racist attitudes, while American cabinets have long been the most multicultural of any in the G20, including Australia (though in recent years Canada has set the standard).

There is a real possibility that next year’s presidential election could be a contest between two candidates of colour, with popular Republican senator Tim Scott of South Carolina taking on Vice-President Kamala Harris or another rising star such as Maryland governor Wes Moore. American debates about race and democracy are more visible, vocal and vociferous – and sometimes violent – but adversaries who mistake those fights as signs of decline and not also as acts of renewal risk falling into what Robert Kagan calls in his new book, The Ghost at the Feast, “the America trap”.

The only Americans we have

What, then, is a close US ally like Australia to do? There is no indication that Labor or the Coalition is going to choose neutrality or distancing from the US – not with Chinese coercive pressure a reality and other close partners such as Japan and South Korea choosing to reinforce the American alliance system rather than defect. America remains the indispensable power despite itself.

In a world without US leadership, Vladimir Putin would today be ruling Ukraine through proxies in Kyiv, Taipei might have succumbed to Chinese coercion, and corporations would depend on China’s increasingly predatory economic model for growth, without the alternative provided by an open and innovative American economy.

Hedging against uncertainty about America may seem a sensible choice for Australia and would likely not collide with Washington’s expectations of Canberra when one considers how it would look. An extreme hedging option for Australia would be to pursue independent nuclear weapons. However, there would be no public support, a dangerous regional backlash and a significant weakening of deterrence already provided by US nuclear weapons.

A more logical and subtle hedging strategy would be to pursue sovereign military capabilities designed for the defence of Australia. At the top of the list would be guided weapons and high-end attack submarines.

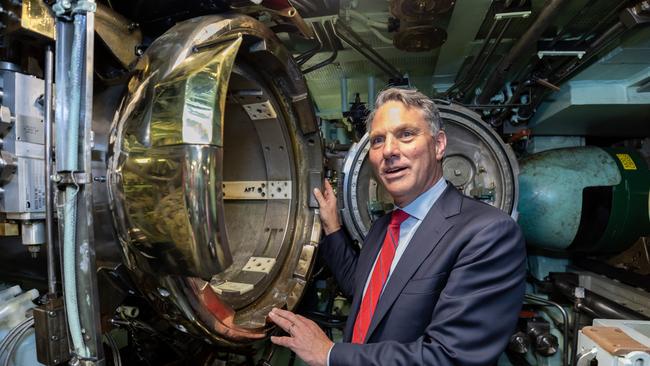

Defence Minister Richard Marles has emphasised that these capabilities are essential to secure Australian sovereignty in a more dangerous geopolitical environment – and that the alliance with the US is essential to obtaining them. The US provides the best and most advanced kit with the most reliable supply for any geopolitical threat Australia would face. The road to sovereign defence capabilities goes through the alliance, in other words, and the complexities of tech transfer notwithstanding, the US is all in for helping Australia get there.

Another logical hedging strategy would be to enhance security co-operation with Japan, India and other middle powers such as South Korea. Such moves – the security agreement prime ministers Anthony Albanese and Fumio Kishida signed in Perth in October is an example – have been warmly welcomed in Washington. Once again, Australia does not face a choice between the alliance or Asia – it is a natural complementarity.

Other big decisions are coming down the pike. If the US leases attack submarines to the Royal Australian Navy, for example, how will the joint crews be commanded in the event of a contingency? As China’s missiles bring Australia into range – the first such territorial threat since the Cold War and really since World War II – how will Australia and the US modernise co-operation on nuclear strategy and extended deterrence? In the past, Australia assumed there would be 10 years before these issues had to be sorted out for the defence of Australia against direct attack. The government’s recent Defence Strategic Review now predicates that warning time is essentially zero. Australia is not likely to form a comparable command with the US even in the current geopolitical climate, but decision-making will have to be more agile and intimate.

Whatever the new arrangements, there will have to be analysis and debate by parliament, congress and the public.

Interestingly, for a long time the US-Australia alliance did not rely on think tank forums to facilitate such debates, unlike the US-Japan, US-South Korea or trans-Atlantic alliances. This is changing with the new presence in Washington of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, the establishment of the Australia chair at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, and the expansive research agenda of the Sydney-based US Studies Centre and other counterpart institutions in the US and Australia.

Debate on and criticism of America should continue. The founding fathers vowed to create a more perfect union – they did not claim they had one. Ultimately, the US is a superpower that has sustained its leadership role because Americans are not afraid of criticism. China has undercut its own rise by bullying governments and citizens abroad who dare reproach it for its abuses of human rights, lack of transparency on Covid or military pressure on neighbours. Americans may suffer at times from a reasonableness burden (countries expect the US to be the more reasonable of the superpowers in any clash), but in the long run it is that reasonableness and openness to criticism that makes America the indispensable power.

Michael J. Green is chief executive of the US Studies Centre. This is an edited extract from his essay in Australian Foreign Affairs, Issue 18, out Monday.

-

Is the alliance making us less safe?

Sam Roggeveen

Last October the ABC’s investigative journalism program, Four Corners, revealed news that sent ripples through Australia’s national debate about defence policy, but ought to have made waves. The revelation, subsequently confirmed by government, was that Australia and the US had agreed to expand the RAAF Tindal air base, about 300km south of Darwin, so that up to six American strategic bombers could operate from there.

Australia has supported US bomber rotations in the Northern Territory since at least 2006, but with this air base refurbishment the US and Australia are effectively integrating RAAF Tindal into America’s war planning. Australia previously had hosted US bombers for training purposes, but this initiative will allow American bombers to fly operational missions from Australian soil, including in wartime.

If the Tindal decision passed with little comment, the same cannot be said of the March 14 AUKUS announcement in San Diego, California: Australia would acquire three to five second-hand Virginia-class nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs) from the US, and then a class of new-generation submarines designed and built with help from the US and Britain, to be known as SSN AUKUS. Anthony Albanese and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, alongside President Joe Biden, also announced Submarine Rotational Force – West: from as early as 2027, Britain will rotate one SSN through the newly refurbished HMAS Stirling naval base in Western Australia, while the US will contribute four. Australia also has committed to developing a new $10bn east coast base for its nuclear-powered submarines. It, too, will be capable of supporting US and British submarines.

Almost all observers agree these initiatives signal a closer Australian alignment with American foreign policy objectives – they will bring Australia into a tighter American embrace and increase the likelihood that Australia will fight alongside the US should Washington and Beijing go to war, whether over Taiwan or for another reason.

Media coverage in the wake of the Four Corners scoop placed a lot of emphasis on America’s bombers being “nuclear capable”, but that is something of a distraction. US bombers don’t routinely carry nuclear weapons, and certainly not to airfields that aren’t specifically designed to accommodate them. America’s air-launched nuclear weapons are stored in only five countries outside the US, all in Europe, at bases built to higher-than-normal security standards. If the US ever wanted to store nuclear weapons at RAAF Tindal, such a move would be preceded by long political debate in Australia, and we would observe specific building works and security upgrades at the base. That is not the intention right now.

Yet even without nuclear weapons, US bombers flying out of Tindal could play an important role in the nuclear balance between America and China because they could be tasked with striking China’s nuclear infrastructure, such as missile silos and bases, command and control facilities, early warning radars that let China know of an impending nuclear attack, and air defence facilities designed to keep its nuclear bases safe.

Tindal could not only help the US win a conventional (non-nuclear) war but also play a part in neutralising China’s nuclear forces. It is clear why American bombers flying out of RAAF Tindal would be an important target for Chinese forces.

Australian submarines and missiles

In February, the Prime Minister boasted that nuclear-powered submarines represented “the single biggest leap in our defence capability in our history”. He’s right.

Assuming the submarines are delivered, they will represent a major boost in Australia’s military capabilities because nuclear-powered submarines are so much more effective than the diesel-powered boats we now operate. Nuclear power allows submarines to operate at higher sustained speeds, with infinite range and endurance. The only limits are crew stamina and food supplies.

Nuclear-powered boats are also larger, which means they can carry more weapons.

Australia could use its nuclear-powered submarine fleet to defend the continent from military aggression close to our shores. Australia has a huge coastline, after all, so submarines with long endurance and high speed would be useful. But while the government is reluctant to say exactly what it wants the new submarine fleet to do, it seems clear that the intent is not to protect Australia’s coastline directly but to operate thousands of kilometres to our north. Nuclear-powered submarines would be ideally suited to operating off the coast of China, hemming the People’s Liberation Army Navy in home waters. And the requirement for the new submarines to carry Tomahawk cruise missiles can be interpreted only one way: Australia wants the capability to strike targets on Chinese soil.

In the event of war, what would the AUKUS submarines do when operating near Chinese waters? Their missions would likely be similar to the US SSN missions described earlier: sinking Chinese naval ships and submarines, blockading ports or striking targets on the Chinese landmass with long-range cruise missiles. One difference, however, is that, owing to the sensitivity of nuclear weapons arsenals, particularly during a war that could easily go nuclear, the US would be unlikely to subordinate nuclear-related missions to Australia’s submarine fleet, such as striking China’s nuclear infrastructure on land or sinking China’s small fleet of ballistic-missile submarines. Still, owing to their range and endurance, Australian SSNs will be more likely to encounter Chinese ballistic-missile submarines in the course of their operations.

Clearly, having these capabilities raises the likelihood of Chinese military strikes against Australia. But we can go further: they make it more likely that a crisis will escalate into a war because they incentivise China to launch a pre-emptive surprise attack. In a crisis with the US that is poised on the brink of conflict, China may feel it is in its interests to strike before Australia’s submarines leave port and before its hypersonic missiles are dispersed to remote locations, simply because it is so much easier to target fixed sites. In turn, this creates an incentive for Australia to pre-empt the pre-emptor. We would be tempted to use our weapons before we lose them.

The political symbolism of Australian strikes against Chinese territory also increases the danger to Australian territory because China would be unlikely to let such a blow by a much smaller power pass without retaliation.

AUKUS calculation

If a war between the US and China erupted tomorrow and Australia decided to contribute militarily to the US side, it would not be a critical player. We could offer a destroyer and frigate to protect a US aircraft carrier from attacks by submarines, ships and aircraft. The Collins-class submarine fleet could play a role. Aerial refuelling aircraft would be in high demand, and the RAAF could offer up to seven of those. We could hunt Chinese submarines with our P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft. Perhaps the most potent capability we could offer would be to send a squadron of F-35 fighters to Japan to hit targets in China.

But even if Australia did all of these things, given the scale of such a war, they would be niche contributions. By contrast, the combined effect of hosting US bombers and submarines, and having our own nuclear-powered submarines with the ability to hit the Chinese mainland, will substantially raise Australia’s status. Australia will be a bigger target.

Australia takes these risks because we have concluded that, on balance, we are likely to be safer within the alliance, with all the obligations it imposes, than outside it.

But if China’s capabilities to strike Australia are set to increase, and if we are raising China’s incentives to do so, then the judgments we have previously made about whether the risks of the alliance outweigh the security benefits need to be re-evaluated. Does the trade-off between the risk of being targeted and the security provided by the alliance still favour Australia? The answer to that question depends on the value Australia places on US military dominance in Asia, including America’s ability to decisively defeat China in a war over Taiwan. If American victory in such a war is a vital interest for Australia, then it is proper for Australia to contribute to sustaining that dominance.

Australia has taken the decision to bring US combat forces, and its military strategy to fight China, on to our shores. We have also chosen to build military capabilities of our own that are designed expressly to contribute to American operations to defeat China. These fateful decisions threaten to draw Australia into a war that is not central to our security interests and that could end in nuclear catastrophe. Yet America’s reluctance to fully commit to military supremacy over China is a small blessing because it presents an opportunity for Australia to bend American objectives towards a more achievable and stabilising role of balancer rather than leader. That would be a sustainable objective for the US-Australia alliance, and a more justifiable basis on which the US could deploy forces to Australia.

But as a military stronghold for a US effort to achieve regional dominance and defeat China in a war over Taiwan, Australia is materially eroding its security for no gain.

Sam Roggeveen is the director of the International Security Program at the Lowy Institute. This is an edited extract from his essay in the latest Australian Foreign Affairs, Issue 18, out Monday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout