Is the partygate over for embattled British prime minister Boris Johnson?

A Johnson recovery is unlikely. But absolutely everything about his career so far has been unlikely.

You were the hope of conservatives around the world. You showed centre-right parties in every Western democracy that they could boldly assert their national sovereignty against the undemocratic diktats of multilateral bodies. In your magnificent Brexit referendum victory, you showed us that a conservative leader with conviction and energy and flair could triumph even when every speck of the elite zeitgeist, all the main political parties and almost all of the mainstream media, were dead against him. The BBC ran wall-to-wall propaganda against Brexit and still you won that referendum.

Then in the election of 2019 you demonstrated, much more even than Donald Trump in the US, that conservatives could win working-class votes, building a new majority, greater than any since Margaret Thatcher’s, on the basis of the common sense and patriotism of ordinary people who had never before voted Conservative in their lives.

Your outsize personality was an asset for conservatives, who became the fun brand. There was just a tiny touch of Winston Churchill. Not only the brilliant wit, endless good humour, immense self-assurance, but the sense that only you could have won Brexit. Without your leadership, history would have been different.

The story of Johnson’s rise and apparent fall could never have been conceived by a script writer or novelist. Only the incomparable creativity of disordered reality could produce such astounding reversals of fortune, and unlikely personality.

This week Johnson had to weather a no-confidence motion against his leadership because 54 Conservative MPs petitioned to hold such a vote. Johnson “won” the vote 211 to 148. But that was a terrible result, almost unbelievable for a prime minister who won a landslide majority 2½ years ago.

On historical precedent, you’d say Johnson’s leadership is cooked. More than 40 per cent of his parliamentary colleagues want him booted out. Theresa May in 2018 similarly won a no-confidence vote, by 200 to 117, a slightly better performance than Johnson. She was gone from the top job within six months. In 1990 Thatcher sustained a similar “victory” in a no-confidence vote, 204 to 152. That was the end of her.

But in May’s case there was an obvious alternative leader and a chief plotter of her destruction, namely Johnson. The same was true with Thatcher. Michael Heseltine was the chief insurrectionist, though he didn’t finally get the top job.

John Major in 1995 called a leadership vote himself and won it 218 votes to 89. With no clear alternative leader, Major staggered on to the 1997 election to be trounced by Labour’s Tony Blair. Thus there is a tiny sliver of hope for Johnson in that there is no obvious alternative to him and no defining policy disagreement. So, perhaps like Major, he might just conceivably make it to the next election.

Just as Conservative party disunity hurt Major, the scores of Conservative MPs and conservative commentators who have denounced Johnson must hurt his re-election chances.

Rod Liddle, a brilliantly witty columnist in The Spectator, calls for a government that occasionally tells the truth. William Hague, a former Conservative leader who didn’t win an election but became the best foreign secretary, called for Johnson to step down for the good of the party and nation.

Johnson is in all this trouble for reasons that are both insanely trivial and deeply disheartening. He has always been reckless in his personal behaviour, but never malicious. All his former wives and mistresses, and all of his children, or at least the ones the public knows about, seem to retain affection for him. He has been promiscuous and relentlessly unfaithful in all his romantic attachments – except perhaps for his current marriage – and that is a sign of a serious character flaw. But he has been so good-humoured that somehow it never killed his political career.

David Cameron, whose prime ministership was destroyed by Johnson’s Brexit campaign, once described him as “a greased piglet” it was impossible to keep hold of.

It’s surely not drawing too long a psychological bow to say Johnson, unlike any conservative stereotype, thrives in chaos, disorder, mayhem and crisis. As others have observed, the political virtuosity he displays in surviving crises is breathtaking, but it’s equally staggering how fantastically bad is the judgment he displays getting into trouble in the first place.

The great debacle of Partygate is just such a case. Johnson received one police fine for attending his own birthday celebration, for 10 minutes in an official room, during Covid-19 lockdowns. The most sinister feature, a cake, was present. The Metropolitan Police ended up investigating 12 functions in and around Downing Street and issuing 126 fines. Later, senior official Sue Gray issued her own report. She didn’t like the look of 16 functions. She identified a failure of leadership at the top of 10 Downing Street – for which read Johnson, his wife Carrie and his senior staff. A long trail of WhatsApp messages were part of the evidence. Some of the participants clearly realised they were breaking Covid-19 rules. Grey also criticised some plainly anti-social behaviour.

Here’s where the personal, the political, the policy and the quality of government elements of Johnson’s personality did not mix well. At the time Johnson and his colleagues were modestly but repeatedly breaking the rules, ordinary Brits were prevented from seeing their dying mothers and fathers in hospitals and aged-care homes because of Covid-19.

Britain, like Australia, had severe lockdowns. The Queen, forever the model of modesty, restraint, correct behaviour and duty, mourned her beloved husband Philip seated alone in the church during his funeral because of social distancing and limits on numbers at funerals.

That Johnson and his government imposed such harsh rules and then didn’t follow the rules themselves outraged a good chunk of people. Up until then, much of the population enjoyed Johnson’s roguish personality. When caught out in minor indiscretions, sometimes major indiscretions, Johnson often admitted them, or at least didn’t seriously deny them, pleaded that they weren’t really so serious, made a joke or a series of jokes at his own expense, cheered you up with a twinkle in his eye and moved on.

Up until Partygate, a lot of the British public have enjoyed, or at least partly enjoyed, Johnson’s many good-natured transgressions the way Australians did with Bob Hawke. Johnson seemed to be having a laugh at the people who were always scolding ordinary folks, not least the media. In Partygate, by contrast, Johnson seemed to be laughing at ordinary people by requiring them to do one thing while he did another.

It totally reversed the fellow feeling Johnson established with so many voters when he endured Covid-19, hospitalisation, intensive care and the threat of imminent death, and then emerged with such graciousness and gratitude to the doctors, even more to the nurses, who had looked after him in a National Health Service hospital.

Johnson is quite the most remarkable democratic politician I’ve interviewed in more than four decades in journalism. The effort he puts into winning every person he meets is prodigious. He is not only witty and fun, he is a dedicated charmer. I interviewed him when he was British foreign secretary and he flattered me outrageously by pretending to have read my columns for years. A couple of weeks after the interview I received a handwritten note from him thanking me for doing the interview, as if I would have had something better to do.

Yet the other side of Johnson was evident as well. He mistakenly revealed a joint British-Australian intelligence operation to me that he had been briefed on but presumably forgot was confidential. Or perhaps he intended to give me a scoop, though he didn’t ask me not to quote him as the source. Very shortly after the interview, a worried senior British official rang to say the foreign secretary had not meant to tell me this, its publication could hurt ongoing operations, so would I refrain from publishing it?

OK. But what a strange mixture of qualities in one 40-minute interview.

Partygate is not the only problem Johnson faces but it’s by far the worst. Yet it’s also fair to ask: is there a trace of double standards in the venom and hostility now being flung at Johnson?

Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews, who imposed some of the toughest lockdowns in the world, was twice fined for breaking his own mask mandates. This was embarrassing for Andrews but no one suggested it made him unfit for government.

But just as Trump has uniquely polarised the US, so Brexit has uniquely polarised Britain. Some of the sheer rage aimed at Johnson comes from those who hate Brexit and desperately want it to fail, and Johnson to fail, and perhaps its present incarnation wants Britain to fail too.

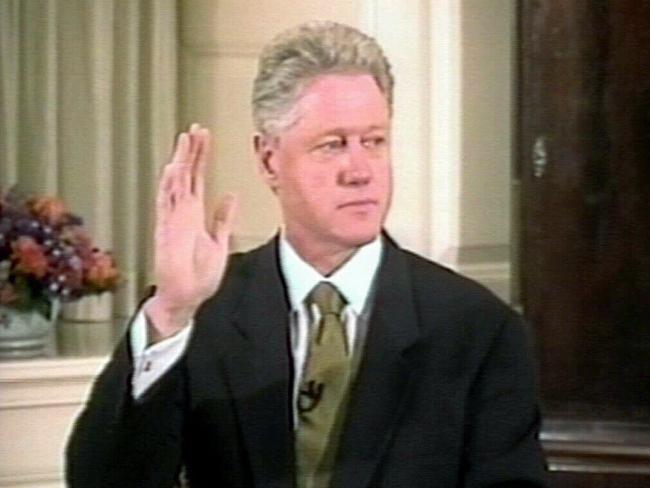

All through the Western world it is the centre left, green left and further left that command the heights of media and culture. Compare Johnson’s fate with that of former US president Bill Clinton. Clinton deliberately, unequivocally lied under oath about his affair with Monica Lewinsky. Republicans criticised him but most media and all the woke folk supported him, even though the power disparity between him and Lewinsky was colossal and telling the truth under oath is a pretty fundamental obligation.

But Johnson will never get an even break from the upholders of received opinion and public morals. He certainly deserves censure for breaking his own rules, even if there was considerable fuzziness about the status of these gatherings. Johnson has lived his life in the grey zones and the fuzziness of rule breaking. You can’t do that when you’re prime minister.

Still, Johnson has three clear things going for him that make a political recovery, though unlikely, not altogether unimaginable.

There is no clear alternative within the Conservative Party. There is no defining policy issue his critics want to prosecute. And he himself is the most unpredictable and quicksilver of all modern politicians.

But he has a few things going against him as well. He faces two crucial by-elections on June 23. If the Conservatives lose both seats and are absolutely hammered, that may be a point of new rebellion. So far, there has not been a mass resignation of cabinet ministers from the Johnson government. In truth, it’s a pretty mediocre cabinet. One of Johnson’s failings is a dislike of big figures around him. There is no other way to explain the ridiculous failure to promote Tom Tugendhat, the chairman of the parliamentary foreign affairs committee, into cabinet.

But if Johnson loses cabinet ministers, as May did, or enough Conservative backbenchers start voting against the government in the House of Commons, which also happened to May, his position could become untenable.

Soon enough too the parliamentary privileges committee will hand down a report on whether Johnson lied to parliament about Partygate. Johnson, somewhat like Clinton, has always believed he’s entitled to lie about matters of personal behaviour. Often the lie comes with a conceding wink of the eye. But again, that just doesn’t work for a prime minister.

Finally, he hasn’t run a very good government. Having achieved Brexit, he hasn’t taken advantage of it with deregulation or supply-side reform. The tax level and the size of government are bigger than they’ve been for 70 years. Economic growth will be slower this year than in any other G20 country but Russia.

In this Johnson reveals another fundamental truth – Covid-19 has gravely damaged the centre-right project all around the world. Centre-right governments have been as profligate as any and have lost their credential as superior economic managers. Covid-19 has witnessed a massive expansion of the state. That helps centre left rather than centre right.

If Johnson is to stage an unlikely recovery, it must come from rediscovering Conservative policies – lower taxes, greater home ownership, tough on crime, strong borders, assertive against the EU over Northern Ireland, reform of transport union power, strong support to democratic Ukraine.

A Johnson recovery is unlikely. But absolutely everything about Johnson’s career so far has been unlikely.

Boris, Boris, Boris, Boris. How could it come to this?