Irish doctor Ivor Browne shut down Dickensian mental health prisons

Ivor Browne believed much mental illness was sparked by youthful traumas that some of us never properly processed.

OBITUARY

Ivor Browne, psychiatrist, born Dublin, Irish Free State, March 18, 1929. Died aged 94, Dublin, Ireland

The unseeable connections between the psyche and the soma have been debated for centuries – especially after French physician Philippe Pinel had the chains and straitjackets removed from the inmates of an “insane asylum”. Thereafter he spoke to these patients daily – taking detailed notes – in order to gauge the nature and degree of their psychological illness.

In 1797, he took this emerging understanding of the mentally unwell to the Pitie-Salpetriere Hospital in Paris (precisely 200 years later the Salpetriere would briefly gain world attention when Diana, the Princess of Wales, was taken there mortally wounded after a car crash nearby).

Pinal stayed at Salpetriere for the rest of his life studying the patients and developing his theories of the classifications of mental illness and the humane treatment of those who suffered from them. He changed the way the world viewed these patients.

Nonetheless, even advanced nations, until quite recently, would keep the afflicted in coercive Dickensian confinement.

The situation in Ireland was particularly acute. By the mid-1960s the country was incarcerating proportionately more people than the Soviet Union, where it was a common punishment for perceived enemies of the state. Indeed, 0.7 per cent of the Irish population was in a psychiatric institution.

Ivor Browne liberated them and his different thinking would transform the way influential psychiatrists thought about the mentally unwell. He wasn’t meant to be a psychiatrist; he had busked around the country after the war and planned to become a jazz trumpeter.

He studied medicine to appease his parents. But he took to psychiatry, starting an internship in a neurosurgical unit.

There, every weekend, he would witness patients from Grangegorman, the local psychiatric hospital built in the era of Ireland’s Lunacy Act, undergo a lobotomy in which “holes were drilled on each side of the temples and a blunt instrument inserted to sever the frontal lobes almost completely from the rest of the brain”. The hospital routinely used electro-convulsive therapy.

Browne did not want the mentally ill to be contained by walls nor by drugs, and a two-year stint at the Harvard School of Public Health gave him ideas as well as broad experience with newly developed psychotropic medications. By 1966 he was Dublin’s chief psychiatrist and arranged for the ceremonial demolition of the brooding stone wall that fenced in Grangegorman’s inmates. He wanted its inhabitants to be part of the community and to receive one-on-one care.

Browne accepted that sometimes medication was vital to the treatment of psychoses and depression, but he fought against the notion that when patients began to feel unwell, they should see a doctor and be prescribed medications. He believed this rendered them helpless and trapped in a cycle of illness and habit-forming pills. To bring about real change “the person has to do the work of changing themselves, with the support and guidance of a therapist”. This would transition from dependence to independence.

“This concept of ‘self-organisation’ is synonymous with what it is to be alive,” he wrote in 2010. “Anything that diminishes our state of self-organisation lessens our control over and management of our health, and will be a step towards sickness.”

He believed that often a traumatic episode in someone’s young life – perhaps sexual abuse, a dysfunctional family life, or an act of violence – could later express itself as bipolar disorder or clinical depression. He wanted his patients to find the source of their problems. His most controversial theory was of the “frozen present”, in which a traumatic episode shuts down a person’s system so it is never processed and formed into a memory. As a result, unlike the diminishing grief of a lost loved one, this trauma can be triggered at any time with serious consequences.

His work has influenced some of the world’s leading thinkers in the area: Canada’s Gabor Mate, and Boston psychiatrist, researcher and author Bessel van der Kolk.

The people he treated successfully became noisy supporters, but there were many who believed the unorthodox outlier was too dismissive of the value of medication, particularly when it came to the seriously depressed who might harm themselves.

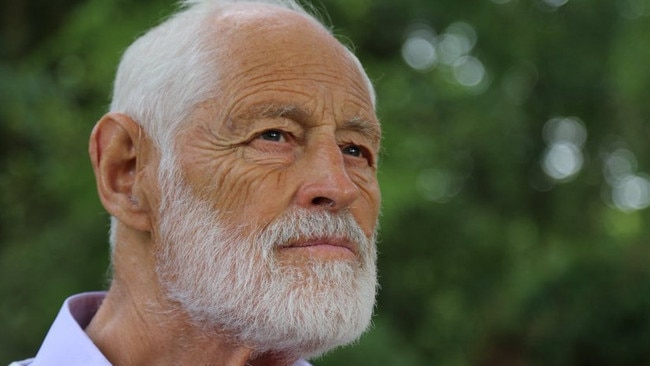

Browne was a strikingly tall, gently spoken man who looked as if he had stepped from the pages of Tolkien – and his house was named Gandalf. “I may be crazy,” he said in 2017, “but it’s no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society.”