Iran’s nuclear threat ‘a defining test for Biden’

Trump acheived more in the Middle East than many realise, and Biden is right on the cusp of blowing it. He can’t say he wasn’t warned.

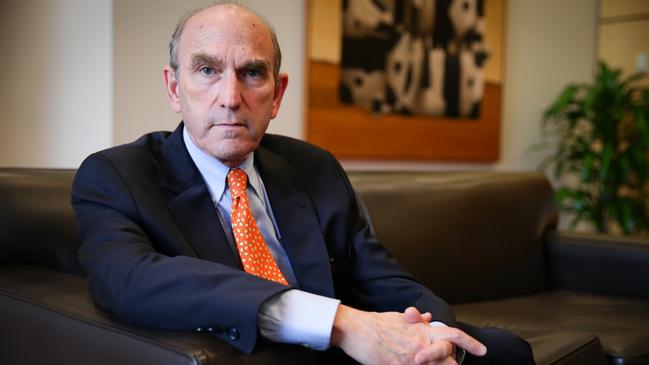

This is the view of Elliott Abrams, who was Donald Trump’s special envoy on Iran. It is also a view widely shared at the highest levels of the Australian national security establishment.

Abrams is a distinguished Washington foreign policy figure. He is not a dyed-in-the-wool Trumpist. He held senior positions at the State Department under Ronald Reagan and was deputy national security adviser under George W Bush. He criticised Trump during the 2016 election campaign and is one of very few mainstream Republicans who did so to later serve at a senior level in the Trump administration. He is now a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

His view of what we might term the axis of authoritarians is sobering: “This is a combination that is visible in many pars of the world — Russia and Iran in Syria; Russia and China and Iran in Venezuela. It has as its target the US and the free world, to use the old terminology. It wants to damage the US alliance system that is built around NATO, Japan, South Korea, Australia. That is what they’re trying to weaken.

“They (China, Russia and Iran) do have tensions among them, but they have more in common trying to weaken all of us.”

For a senior official who stayed with Trump to the end, Abrams has a nuanced and balanced view of the foreign policy of Joe Biden’s administration so far. He praises its bipartisan attitude to China, but thinks it is on the brink of making a huge mistake with Iran. He also thinks there is a real prospect of military action, eventually, by the US or Israel to stop Iran’s nuclear weapons program.

In the course of a long telephone interview, I asked Abrams whether, as a mainstream Republican foreign policy figure, he had ethical qualms about going to work for Trump.

“Not really,” he says. “We have a two-party system, and when your party is in power you should try to work for the administration and do what you can to help.”

Nonetheless, Abrams has no criticism of those who worked directly to Trump and found him so difficult that they resigned, and he has no criticism for those who resigned after the insurrection at Capitol Hill on January 6. Many Republican foreign policy professionals had signed public letters criticising Trump during the 2016 campaign and they never went to work in the administration.

Abrams says: “I knew a number of very good people who had signed those letters and a year later they had reconsidered and were prepared to come into the administration. They were all blackballed. That was a big mistake. Think of previous Republican presidents, of Ronald Reagan taking George HW Bush as his vice-president after Bush accused him of voodoo economics. You try to reunite the party. But for Trump, it was all personal.”

A final personal note on Abrams. As a young man he was a relatively big figure in the Reagan administration. He got caught up in the investigation of the Iran/Contra affair, in which some of the Reaganites conspired to secretly send weapons to the anti-communist Contra rebels in Nicaragua. A special prosecutor went ballistic in the accustomed Washington way, and after endless prosecutorial pressure, Abrams pleaded guilty to two minor misdemeanour charges of not providing sufficient information to congress. The charges were regarded as so paltry that George HW Bush, the very embodiment of probity, subsequently pardoned Abrams, and George W Bush brought him back to serve as deputy national security adviser.

Now he is worried that Biden stands on the brink of a potentially disastrous mistake with Iran. Trump withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the deal the Obama administration did with Tehran. This deal, which was widely criticised at the time and opposed by Republicans, allowed a certain level of uranium enrichment by Tehran, afforded legitimacy to the ayatollahs’ regime mastering all the stages of the nuclear cycle, and had quite short sunset clauses on all manner of weapons and technology that meant Iran would be well placed to pursue nuclear weapons down the track.

Since the Trump administration withdrew from the deal, the Iranians have breached its provisions. The Biden administration wants to go back to that deal. Abrams thinks this is potentially a grave mistake.

“There is a fallacy at the centre of their (the Biden administration’s) policy,” Abrams tells me.

“They do not really defend JCPOA as an adequate long-term solution. What they say is let’s get back to the JCPOA and then continue the diplomacy, to make the agreement longer and stronger, to stretch out the sunset clauses and include issues like missiles and Iran’s regional misconduct.

“To get back to the JCPOA, Iran has to come back into compliance with the agreement and we have to lift all economic sanctions. But here’s the fallacy: if you get to this point, you have destroyed all American leverage, and there is no reason to believe Iran will negotiate and accept additional limits.”

I ask Abrams what would have happened if Trump had been re-elected and continued with the tough sanctions. He says: “We had a theory — we’ll never know if it would have worked. Iran was under enormous pressure. If Trump had been re-elected, the Iranians would have realised they faced four years or more of this unless they agreed to negotiate a much better deal. They have a presidential election in June and we thought we had a very good chance of persuading them to negotiate a better deal.”

But even if that had not worked out, the sanctions still achieved outcomes on their own. “There’s pretty good evidence that sanctions have led to a decline in the amount of money Iran gives to (Lebanese terrorist group) Hezbollah. Hezbollah was much better financed 10 years ago. Sanctions do weaken your enemy,” he says.

Abrams believes the Obama administration negotiated the JCPOA incompetently: “We (the US) went into the negotiations with the unanimous view that Iran should not do any uranium enrichment. If you ask (then secretary of state) John Kerry why the Obama administration gave that up and allowed Iran to enrich uranium, he’d say no agreement was possible unless we gave it up. I don’t accept that. Many Europeans, even those sympathetic to the Obama approach, thought the American negotiating team was poor and made concessions they did not need to make.”

Iran has abandoned the restrictions. Having been supposed not to enrich uranium beyond 3.7 per cent, they have done so to 20 per cent and, Abrams says, have 15 times more enriched uranium than they were supposed to have.

He has no doubt Iran wants nuclear weapons: “That’s the only logical conclusion from this behaviour. We have seen how countries behave which want nuclear energy but aren’t after nuclear weapons. It’s not like this. The Iranians have consistently lied and cheated. You don’t need to enrich uranium at all for nuclear energy; you can import and export as much of it as you need.”

Given the threat Iran poses to European security, why have the Europeans so consistently been against tough US action? Abrams offers a thoughtful response: “That’s a difficult question. I think the answer lies in this thinking — if you don’t take whatever is the best negotiated option on offer from the Iranians, what is the alternative? Maybe they just go down the road of nuclear weapons. But as (former secretary of state) George Shultz said, if they do that, then maybe you have to do something about it. That’s what the Europeans can’t contemplate, and it’s what the US can contemplate.”

Abrams believes that if Iran keeps on the road to nuclear weapons, then either the US or Israel will eventually take military action: “I believe that Israel or the US would act to prevent Iran from building a usable nuclear weapon. In both cases, there are two questions: what is the point on the road where one must finally act militarily, and will we have the requisite intelligence to know when that point has been reached?”

One of the greatest problems in Western discussion of Iran, Abrams believes, is the extreme difficulty the Western mind has in grasping the nature of a truly religiously, or ideologically, motivated national government: “The fundamental problem in Iran is the nature of the regime. It is the world’s largest state supporter of terrorism and extremely repressive. It’s too dangerous to let that regime develop nuclear weapons.

“The people in power in Iran are almost exclusively motivated by their view of Islam and their view that Iran has a special role as the world centre of Shia Islam. It’s very hard for people in the West, who are mostly secular, to understand that they really mean what they say.

“The Ayatollah Khameini is a cleric. The people who run the country are clerics. No doubt some have embraced corruption and lost their faith. But there is no reason to doubt that the leading clerics very much believe in their project.

“One objective of the Obama administration, and this might be true of the Biden administration too, was to build a much more positive relationship with Iran, to show Iran that if we could negotiate our nuclear issue, Iran could open up to the world.

“But that is not an attractive notion to the ayatollahs, that Iran should be more open to the world and look more like the West … that Western culture should be more available. The idea that the goal of his administration should be to bring the greatest prosperity to the Iranian people does not appeal to the Ayatollah Khameini.”

Henry Kissinger, Abrams recalls, once observed that the Iranian leadership had to decide whether their country was a nation a or a cause. They have made their choice, Abrams thinks, but it is not the choice Kissinger would have preferred.

Australia is not a major player in the Middle East but Abrams believes the US/Australia alliance is an essential part of the global security architecture. On Australia, as on China, there is a deep American bipartisanism. But on Iran, policy remains intensely contested. Trump was perhaps more successful in the Middle East than in other regions, with Israel signing so many historic peace agreements and with the Arab Gulf states lining up strongly behind US leadership. Biden could easily blow this all away and get nothing out of the ayatollahs. He certainly can’t say he wasn’t warned.

China, Russia and Iran are acting in an organised formation to damage the US and its key allies, including Australia. Increasingly, it is important for democracies and sympathetic nations to act in concord to promote the values and interests of democracies.