Iranian women are daring to dream that this time their cries will be heard

The timeline of civil disobedience in the Islamic Republic is dotted with false dawns. But there are signs, at last, that the theocrats who have ruled since 1979 may be forced to make concessions.

Today, aged 28, she’s doing what she can to support a new generation of protesters who have taken on the pitiless might of the regime, reaching out to friends and relatives involved in the unrest that was triggered by the death of Mahsa Amini after her arrest by the notorious “morality police”, hoping with all her heart that this time the story will have a different ending.

And there are signs, at last, that the theocrats who have ruled since 1979 may be forced to make concessions – though Almasi insists it won’t quell the protests. “I believe this time it is different,” she says from her home in Sydney’s west. “What we are seeing is the start of a genuine revolution.”

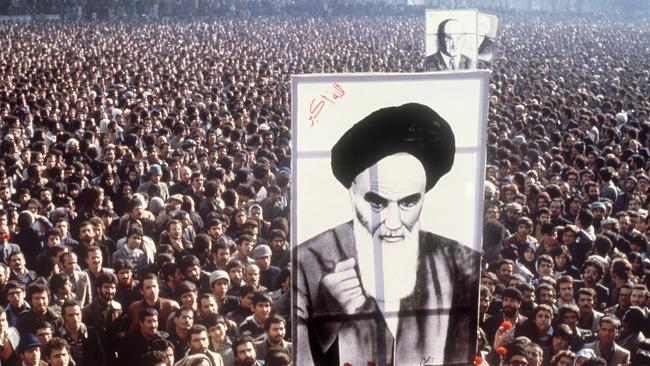

That’s a loaded word given the country’s recent history. The Islamists came to power under the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomenei, overthrowing the secular, US-backed monarchy in a populist uprising. Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi might have encouraged young women in the capital to step out in miniskirts, their hair flowing free, but he also ran a police state every bit as vicious as that set up by the incoming Islamic Republic.

For most Iranians, the thugs of the shah’s Savak were replaced like for despised like by the ubiquitous Basij, the “eyes” of the regime, as well as the so-called “guidance patrols” of the morality police accused of killing 22-year-old Amini on September 16 in Tehran. The reimposition of crippling economic sanctions after then US president Donald Trump disavowed an international deal to slow Iran’s development of a nuclear bomb has left most of the 80 million-strong population poorer than ever.

The parallels don’t end there. The slogan of “women, life, freedom” chanted by the overwhelmingly young demonstrators echoes their grandparents’ war cry: bread, work, freedom. People open their windows at night to shout “death to the dictator”, just as they once demanded “death to the shah”.

Almasi is far from alone in being encouraged by the latest protesters’ resolve.

“During the Green movement in 2009-10 it was mainly students asking for reform … fair elections, changes to the system, things like that,” she says. “The only change people want now is regime change. They want freedom in how they live their lives and I think a lot of frustration with the economy, society and the way the country is run is coming out.”

But let’s not get too carried away. The timeline of civil disobedience in the Islamic Republic is dotted with false dawns. Take the so-called Green movement protests that swept up Almasi as a 17-year-old. These erupted over a clumsily rigged presidential election in 2009 that returned hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Millions took to the streets, only for the campaign to collapse when its leaders were rounded up; most remain behind bars or under house arrest to this day, banned from ever speaking out.

Preparing for university entrance exams, Almasi was determined to march in defiance of her parents’ forcefully expressed wishes. They’re Kurds, a persecuted minority, so she already had one strike against her as far as the state was concerned.

Her mother, Maryam, decided if she couldn’t stop her headstrong daughter, she would join her.

They went to three or four rallies before being arrested. The terror of it still haunts Almasi. She was dragged away to a dusty construction site with other protesters.

One young woman said something to a militiaman: he lashed out, savagely clubbing her head.

“I can still see her blood flowing on … the ground,” Almasi says.

“Horrible, just horrible.”

Even now, she can’t bring herself to talk about the six months she spent in jail, so unspeakable was her treatment and the conditions. But international human rights groups have documented what went on. Beatings and sexual assaults were commonplace for female detainees. The most Almasi will say is: “I was threatened with death.”

Another blow fell upon her release: a gifted student, she had been on track to study law at the prestigious University of Tehran, but was told not to bother applying. Eventually, she was admitted into a less desirable communications course. Yet if anything, that made her more defiant. On International Women’s Day, March 8, 2013, she and two friends plastered the campus with flyers decrying women’s rights violations. “We thought we would be all right,” she remembers.

“We waited until midnight to distribute them – there was no one around.”

When she told her mother what she had done, Maryam insisted she come straight home to Karaj, a satellite city 30 minutes’ drive from the capital. Soon enough her roommate phoned: don’t come back, the frightened girl said, state security had stormed in and tossed the dormitory while looking for Almasi. Strike three.

Her father, Dariush, agreed the family had to flee with her younger sister. They stayed with relatives for a while, and ended up in the Kurdish centre of Kermanshah in the country’s west, moving from house to house. Dariush managed to put enough money together for a flight to Kuala Lumpur. They waited until the airport was quiet over a holiday and he could bribe their way onto the plane.

They weren’t safe, however. When he checked in with people he trusted in Iran, Dariush was told to keep moving; the authorities claimed to know where the family was. They got to Jakarta and paid a people smuggler to put the four of them on a boat to Australia, which was intercepted off Christmas Island in late April 2013. After their claim for asylum was accepted, they were granted temporary protection visas and settled in Melbourne. Sadly, her parents have since separated, while Almasi moved to Sydney two years ago to pursue opportunities as an interpreter and in IT.

As difficult as it is for her to track the drama unfolding in Iran – she continues to suffer PTSD – the young woman found herself drawn into the vortex. She’s in touch with relatives, old friends and classmates who have taken up the cudgels. “It’s a thunderstorm of feelings,” she says.

If she can’t be there to share the danger, the least she can do is share their stories. The regime, as it did to snuff out nationwide demonstrations in 2016 over energy prices and further mass dissent in 2017 and 2019, has shut down the internet. But VPNs that encrypt emails or texts while disguising the user’s online identity offer a viable workaround. Almasi sets up a private connection and passes on the log-in details to the party she wants to communicate with. “This is how people are getting messages and video out,” she says. “It’s why the world knows what the regime is doing to them.”

Her phone and laptop ping through the night with harrowing accounts of the crackdown. As we report in the news pages, the content is confronting. A close friend in Kermanshah messaged her recently, saying: “Next to me someone got shot to his neck. I don’t know what happened.” Another in Tehran wrote: “As soon as someone chanted, guards were shooting and hitting everyone … it was like a war zone.”

You have to admire their stubborn courage. British-based Iran expert Alam Saleh, who is waiting for his visa to come through to join the Australian National University in Canberra, says the tentacles of state security reach into every corner of people’s lives. The Basij – the Organisation for the Mobilisation of the Oppressed – is a militia suborned to the omnipresent Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps, sitting octopus-like at the centre of power and politics.

In a chilling case of life imitating art, the Basij are the “eyes” of the regime imagined by Margaret Atwood in her 1985 book, The Handmaid’s Tale, inspired by the ascendancy of the ayatollahs. Implacably loyal to Khomenei’s successor as supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, the Basij run everything from student guilds to medical schools and multimillion-rial businesses, while mobilising riot squads and a vast network of informers. On top of that, there’s the police, the military, judiciary and a thicket of intelligence providers grouped into no fewer than 12 factionalised and often-rival agencies by Saleh’s count. Very little goes unseen in Iran.

Can the protesters prevail this time? The academic answers cautiously. The regime is clearly “in a bind”, he says. The demonstrations have transcended the initial outrage at Amini’s death after she was detained for allowing a stray lock of hair to escape her headscarf. “The issue of the hijab is not about a piece of cloth,” Saleh argues. “It goes to the regime’s legitimacy, its Islamic identity, and that is not something it can easily compromise on. If they make changes it will be on an informal basis. It won’t and can’t be put down on paper and … I’m not sure that will satisfy the protesters.”

The movement is organic, seemingly leaderless, meaning it can’t be decapitated. Tina Hosseini, a Melbourne-based activist with the Iranian Women’s Association founded by her refugee parents, says strikes have broken out among oil workers and at sugar factories in Haftapeh, a longtime hotspot of dissent. “We’re also seeing people coming out in the most religious cities of Iran like Qom, which hasn’t happened before,” she notes.

The protests don’t have the mass of the Green movement – numbering in the thousands, rather than the five and six-figure throngs from 2009-10 – but they are persisting, despite the regime’s ferocious response. The US-based Human Rights Activists News Agency says at least 224 people have died and 6000 have been arrested to date, with 29 children among the casualties.

A chanting crowd descended on Amini’s grave in her hometown of Saghez in northwest Iraq on October 26 to mark the 40th day of mourning observed under Islamic tradition, setting off a fresh wave of unrest. In the capital, women tossed their hijabs onto bonfires, shouting “Freedom!” Security forces let loose tear gas, beat people with batons and fired pellets, rubber-coated rounds and live bullets at demonstrators in Shiraz and Qazvin, contraband video shows.

Condemning the violence, Anthony Albanese urged the regime to exercise restraint, saying Australians “overwhelmingly stand with the women and the people of Iran in standing up for human rights.”

But Hosseini wants the Prime Minister to back the talk with action and, at a minimum, proscribe the IRGC as a terrorist organisation. She says the government should freeze the assets and bank accounts of any senior Iranian official who has secreted wealth in this country, and also follow a Canadian lead to sever diplomatic and economic ties. It’s quite a list.

Almasi, for her part, has more immediate concerns. Her five-year temporary protection visa expired last month and she’s yet to be told whether it will be renewed, adding to that “thunderstorm” of emotion. She’s torn between her loyalty to those who stayed in Iran to fight the good fight and heartfelt gratitude to be safe in Australia.

Would she go back if the opportunity presented? “That’s a very difficult decision,” she tells Inquirer. “Iran is my home, so I would love to. But I love this country with every cell of my body. Even though the politicians haven’t been kind to us, the Australian people have been amazing to me and my family. If the day comes, I honestly don’t know what I would do.”

No one better understands what is happening on the tumult-filled streets of Iran than Naz Almasi. As a schoolgirl, she was arrested and brutalised by the ayatollahs’ hard-eyed enforcers before fleeing the country with her family to seek a new life in Australia.