IR reforms designed to stop workers being ripped off

The Workplace Minister points his finger at unscrupulous employers.

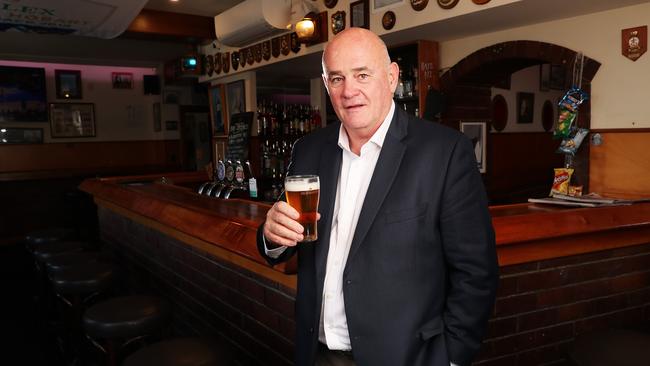

As the chief executive of the nation’s peak hospitality group, the Australian Hotels Association, Stephen Ferguson has been lobbying politicians about industrial relations, taxation, gaming and, naturally, alcohol policies for the past 10 years.

Ferguson was previously chief executive of the Brisbane Racing Club, where he ran the Eagle Farm and Doomben racecourses, employing 100 full-timers and up to 600 casuals on a single day during peak carnival periods.

He personally negotiated separate enterprise agreements with six unions covering workers at the racecourses. Later, after he moved to the AHA, and the Covid pandemic struck, he secured a groundbreaking deal with the United Workers Union for significant award changes to help firms stay open and save jobs.

In short, Ferguson knows industrial relations. He also knows politics and how to cut a deal, holding negotiations with Workplace Relations Minister Tony Burke that resulted in the government this week announcing two changes to the casual employment provisions in the Closing Loopholes Bill.

Burke will remove a provision to ensure heavy penalties not apply to companies that mistakenly misclassify an employee.

He will also make amendments to address concerns that casuals could not be employed with regular patterns of work if they wanted to be.

Ferguson went public to describe the Burke changes as “good news for both casuals and employers alike”. While the original provisions would have been “diabolical” for employers, the changes mean “we can work with this bill”.

Rival business lobby groups, which have sought to present a united front in their curious strategy to try to scuttle the entire bill rather than seek amendments, were furious.

Tania Constable, chief executive of the Minerals Council of Australia, which has committed up to $24m to campaign against the changes, went hard. “These phony amendments won’t help small businesses with the fundamental problem which is the complex definition of casuals that is three pages long and has 15 different tests.”

Ferguson was unimpressed. “Phony is saying you completely oppose the bill but have the intent to rush in seeking amendments late in the piece,” he tells Inquirer. Asked to elaborate, he says: “One business group I have spoken with has the clear intent of waiting till the last minute to table their requests if things don’t go as they plan. They are compiling their plan B right now.” He declined to name the organisation.

“I’m there to represent my members, full stop. Our interest was very narrow. It just relates to casuals. Other business groups’ interests are much wider including labour hire and other issues. So they’re free to go down their path and we’ll choose ours.”

In an interview with Inquirer, Burke says he decided on the amendments to ensure the legislation remains consistent with the government’s policy intention which is “anyone who wanted to remain a casual had no problems being able to do so”.

“There was one section in the civil penalties that created a different problem and could in fact have caused some employers to feel that they needed to convert casuals even if the casuals didn’t want it,” he says. “That was contrary to what the government had always said we wanted to do so that’s why we worked through how to amend the civil penalty provision.”

Burke is also making amendments to the bill’s labour hire provisions to make it clear that service contractors will not be caught by the new laws.

University of Adelaide law professor Andrew Stewart supports the government decision to allow Fair Work Commission orders to ensure labour hire workers cannot be paid less than directly engaged employees for the same work where the host organisation has an enterprise agreement.

But Stewart, who advised the Rudd government on the drafting and structure of the Fair Work Act, maintains the bill’s wording risks capturing service contractors.

“The government has expressed an intention not to bring contracts for ‘specialised services’ within the scope of the new power. But as drafted, the bill specifically includes such arrangements, albeit the FWC may choose not to regulate them,” Stewart says.

Burke says the policy intention embedded in his second reading speech is that “we do not intend to include service contractors except where the service is effectively labour hire”.

“I am completely confident we are going to be able to exclude service contractors,” he says.

“I am also completely confident that once we do that, the organisations that have been running the campaign against the bill will just move to the next issue and will also say in some way we haven’t fixed it.

“Because ultimately what some of these organisations are wanting to do has nothing to do with the arguments they are raising publicly, it’s simply about them trying to do the work for their members so that the wages bill is lower.”

The bill seeks to tackle employers undercutting enterprise agreements they negotiated by engaging labour hire for the same work on lower pay. Qantas and BHP are targets of the laws given their contentious and significant use of labour hire arrangements.

It was not that long ago that many conservative politicians and like-minded commentators cheered on the airline’s hard line cost-cutting industrial relations practices. With Qantas on the nose with the electorate, these formerly sycophantic observers now treat its claims with scepticism, even ridicule.

While Qantas asserted this week that additional compliance costs from the labour hire changes could force it to increase passenger ticket prices, Tony Sheldon, the former Transport Workers Union leader and ALP senator, maintained the airline had been “gaming the system” by putting in place labour hire arrangements that resulted in some employees being paid up to 50 per cent less than directly engaged employees doing exactly the same job.

BHP claims the cost of the labour hire changes to the company will be significantly higher than its previous estimate of $1.3bn annually and threatens to make its $300m apprentice and traineeship program unfeasible.

Burke tells Inquirer: “When I see the $1.3bn figure from BHP, I find it hard to believe that they are underpaying their staff by that much. Some of the things that they’ve done in those figures at different points has been to include all service contractors. At other points, they have presumed that everybody would go to the highest rate of pay within a relevant agreement. The concept here is just really simple: if you’ve agreed to rates of pay in an enterprise agreement then that’s what should apply to your workplace. It’s not more complicated than that.”

Burke points to miners appearing before the inquiry where they claimed the changes will drive up costs and threaten investment before admitting they are not covered by an enterprise agreement, a central requirement to be covered by the laws.

“If you go to a whole lot of the Senate inquiry evidence, it’s clear the extent to which the companies that use the labour hire loophole are giving themselves a competitive advantage over other Australian businesses in what I would say is an unreasonable way,” he says

“You had some businesses appear before the Senate inquiry and at the start of their evidence were saying how disastrous it would be and at the end they were acknowledging they didn’t have an enterprise agreement in place.

“The business groups are showing a high degree of solidarity in this campaign. I’ll give them some organisational respect for it but there is not a lot of integrity in the way some businesses have claimed that this will affect them when they know on any analysis it won’t.”

Stewart says certain companies will face increased costs. “It seems fairly clear that there are some businesses that have exploited loopholes in the transfer of business rules to be able to outsource work and escape from their own, as they very often call them, legacy enterprise agreements,” he says.

“I love that idea of something that’s legacy when what firms seem to mean when they talk about legacy conditions is stupid decisions made by previous management that we now think are way too generous.

Stewart says the government has made no secret of the fact that the mining industry and airlines are two of the likely targets of the proposed laws.

“Clearly, there are going to be some businesses that will end up having to incur extra costs if their indirectly employed workers have to be paid more, or paid the same as their directly employed workers,” he says. “It stands to reason that’s going to increase their costs. It depends whether they try and pass it on or whether it just means slightly smaller profits.

“It’s a question of imposing costs that are derived from an enterprise agreement that those businesses agreed to. It’s not like the Fair Work Commission would be saying we think you should pay your employers more than you agreed. It’s saying you ought to be paying your employees what you agreed to pay them – even if they don’t happen to be your employees directly but employees you have obtained through another employer.

“That’s the essence of the reform. In the end, the principle behind the legislation is a really clear one. If you’ve negotiated to pay certain wages and provide certain conditions, you should keep your promises.”

As a result of the bill’s proposed minimum standards for gig work, Uber claims ridesharing prices for passengers will jump by 60 per cent and delivery fees by 85 per cent. Doordash calculates the average delivery cost could rise by more than 210 per cent, based on having to pay workers minimum pay, superannuation, leave entitlements, penalty rates and allowances such as fuel.

Burke says he expects the reform will introduce a floor on gig work pay, but where that floor lands will be up to the commission.

“I’ve got no doubt that those platforms where the rates flex up and down at different points because of demand, that will still happen,” he says. “There’ll be a floor below which the rates can’t go. And the commission I presume will take into account the fact that rates also flex upwards when they take into account the nature of the engagement.

“People who want the flexibility of being able to choose when they work, engage in and out as they wish, to organise it how they want, all of that will still be there. The commission will be explicitly prevented from those sorts of rostering concepts that are appropriate for an employee relationship and not appropriate in a gig economy.”

He refutes the platform cost estimates, saying the modelling wrongly assumes the commission will “photocopy award conditions and award rates of pay (when) the entire purpose here is for the commission to be able to take into account how gig platforms operate”.

As for any increased cost to the consumer, he says there will only be “some modest pass through”.

Another key component is the proposed criminalisation of wage theft which has the support of Perth cafe worker Bethany Slavik. She was sacked by text this year after she questioned why was being paid below the minimum wage on weekends.

After a Fair Work Ombudsman inspector contacted her boss, she was sacked. She later received backpay and compensation.

“A lot of my co-workers were visa workers and had no other choice and that’s my main reason to continue fighting on this,” she says. “I had no idea wage theft was not a criminal offence. It just seems so strange that it isn’t.”

The Greens want the government to extend wage theft to cover superannuation, and Burke says the government is open to the proposal.

He maintains the government will not bow to the crossbench calls to split the bill. “I view it as a really serious imperative for the entire bill to be passed as soon as possible and I hope as the crossbench continues to look at the detail, and work through the issues, they form the same view.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout