Inside the Canberra rubble

A book about Malcolm Turnbull’s stint as PM, is caught in the wake of #MeToo politics.

That Patrick’s book is on sale at all won’t please Shane Drumgold, the Director of Public Prosecutions in the ACT. On June 23, Drumgold demanded agreement from publisher HarperCollins that the book be recalled from retailers, fearing that it presented “a real risk of serious interference in the administration of justice” in the trial involving rape allegations by Brittany Higgins against Bruce Lehrmann. Failing that, the DPP advised HarperCollins that he would seek an order from the court to that effect.

Drumgold didn’t get his way. The book is still on sale in some bookstores, including online, though not through Australia’s biggest book retailer, Booktopia. Inquirer understands that a deal was cut between HarperCollins and Drumgold so the 4000 books already distributed to bookshops could remain on sale but no further stock would be sent to stores.

The DPP’s intervention raises a critical issue: how do we get the balance right between protecting freedom of expression on issues of public concern and protecting a fair trial?

Patrick told Inquirer: “I don’t know how stopping someone in Perth reading the book will help a rape trial in Canberra.” Understandably, HarperCollins won’t comment beyond saying it has temporarily paused further supplies of the book to retailers.

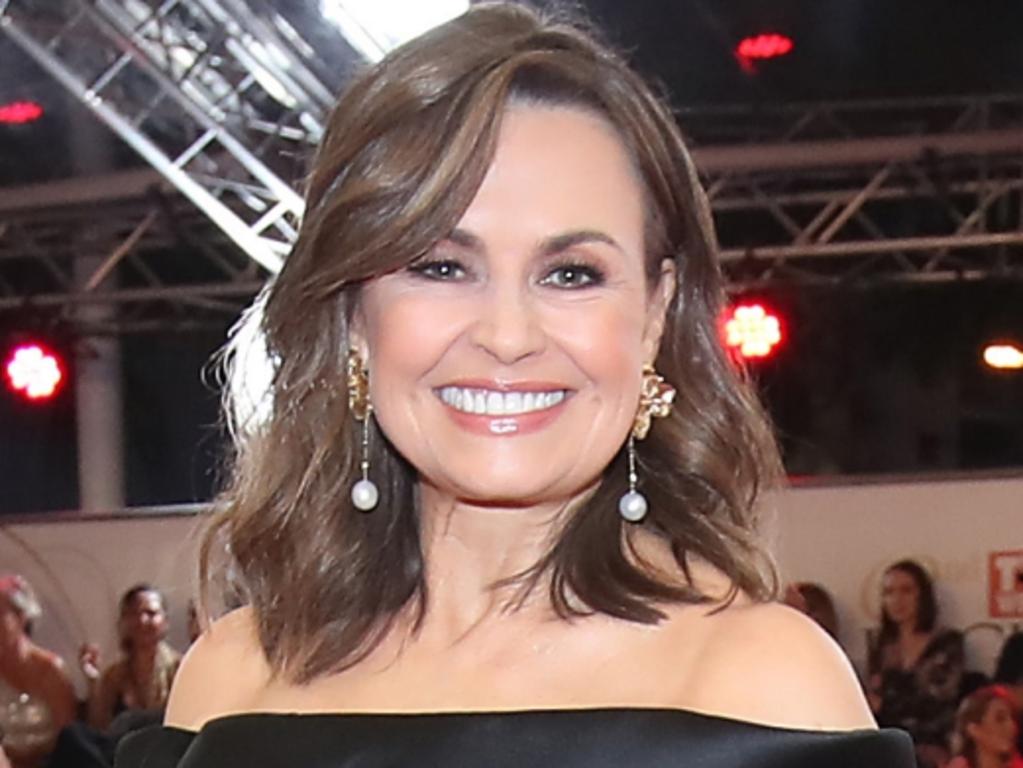

In fact, the DPP’s demand and the deal hatched with HarperCollins makes no sense. The horse bolted when, on June 19, Lisa Wilkinson gave a Logies speech boomed around the country by the Nine Network, and repeated across other media outlets, that caused ACT Supreme Court Chief Justice Lucy McCallum to vacate the rape trial that was set for June 27.

It is worth revisiting why Wilkinson’s foolish and dangerous comments attracted a rare and long overdue spray of judicial wrath about the importance of the presumption of innocence.

Wilkinson’s Logies speech was delivered after a general warning from the judge and a more specific warning by the DPP. That lack of professionalism provides a stark contrast to how Patrick deals with the Higgins issue in Ego.

When McCallum was told Wilkinson received an award for journalistic skill, not the truth of the Higgins story, the judge responded: “Mightn’t good journalism be mindful of criminal proceedings and remembering to insert the magic word ‘alleged’?”

“Somewhere in this debate the distinction between an untested allegation and the fact of guilt has been lost,” she said.

Instead of pursuing Wilkinson for potentially committing a criminal offence, a move that also might rein in the zealots, the DPP instead has overcorrected by interfering with the sale of Patrick’s book.

Ego deserves to be read for many reasons. It is a meticulous, measured and intelligent record of a tumultuous and critical period in Australian politics. Patrick’s style is Truman Capote crisp. Even so, the book could have been 200 pages longer given the material that the Australian Financial Review journalist had to choose from.

Every prime minister dreams about a long and successful period in office, followed by permanent adulation. Patrick’s book is a historical record of why that was not to be for Turnbull; why a talented man has become a disparaged figure in politics, not just Liberal circles. Patrick traces Turnbull’s campaign against fellow Liberals, including his successor, who Turnbull imagined were responsible in different ways for his short-lived and uncelebrated stint as prime minister. While Turnbull and Kevin Rudd have much in common, Rudd won’t be remembered for trying to tear apart his own party.

As Patrick concludes, “Turnbull’s destiny seemed so clear, almost preordained, that when he got to the top, he lacked the self-awareness or humility to lead … Turnbull wasn’t a successful prime minister because, as he demonstrated after leaving office, he was, ultimately, selfish. It was all about Malcolm.”

Perhaps swallowing too many bitter pills is not good for one’s sense of humour.

Turnbull was miffed about the invitation to the launch party for Ego last month. It featured a photo of the book and this: “Please join Malcolm Turnbull* at the official launch of Aaron Patrick’s new book.” At the bottom of the invitation it said: *TBC”. In Paris, Turnbull reportedly complained to HarperCollins chief executive Jim Demetriou claiming the invitation was misleading and deceptive. It was a joke. Comic Rodney Marks impersonated Turnbull at the launch and roasted Patrick.

Gags aside, Ego is important because, despite its title, it is not just about Turnbull. It chronicles the fracturing of a political culture that needed to change. Refreshingly, Patrick captures the good, the bad and the ugly of the reckoning over sexual politics that, finally, came Canberra’s way.

Patrick’s intellectual curiosity and journalistic objectivity won’t please a swath of vigilante journalists in the Australian media. Unlike Wilkinson at the Logies, Patrick is careful to maintain the presumption of innocence when writing about the Higgins affair. He uses those magical words “alleged” and “allegations” as any good journalist does without prompting from lawyers, a judge or a DPP.

This is not the first time Patrick has been drawn, unwittingly, into the messy sexual politics of the day. He featured in Helen Garner’s 1995 book The First Stone: Some Questions about Sex and Power as the public school kid from Ballarat who boarded at the University of Melbourne’s prestigious Ormond College and became a lawyer. Garner altered names and some details to protect identities back then. Patrick is the public school contrast to Ormond’s otherwise privileged private school milieu as Garner explores the pursuit of a man accused of indecent assault by two female students. Though the man ultimately was acquitted by the courts, his career was shattered.

Three decades later, Patrick is a contrast to a different zeitgeist. His book Ego has become a symbol of how a careful, important book can get caught in the maelstrom of #MeToo politics. The DPP’s demand that Patrick’s book be removed from sale is part of an all too familiar feature of modernity’s embrace of #MeToo. Balance is not a virtue any more.

Yet there is a need for a debate about getting the balance right between, on the one hand, respecting freedom of expression and on the other protecting a fair trial. There is no balance in the US; media coverage about an upcoming high-profile trial is untamed, often unhinged.

Australia sits at the other end of the spectrum where many lawyers appear to treat jurors as idiots in need of protection. As DPP, Drumgold is, presumably, well-versed in the law. He will know of a 2004 decision by Justice Philip Cummins in a Victorian Supreme Court case involving Carl Williams and others who at that time had been charged with drug trafficking. The Victorian DPP wanted to stop the media publishing any material that alleged, among other things, that the defendants had been charged with drug trafficking.

Rejecting the DPP’s application, Cummins said: “The experience of the courts is that juries are both responsible and robust and are well able to judge cases solely on the evidence led in court.”

The judge pointed out that juries had the best seat in the house to “see the effort which all counsel put into cases, they see the attention to evidence, they see the testing of evidence and often the destruction of apparently persuasive evidence by cross-examination, they hear the directions of the trial judge and they are in law bound by them. Juries by direction, observation and osmosis assume a proper and responsible role as the judges of the facts, judging the case solely on the evidence led in court.”

Cummins added: “The court will not stand in the way of proper public debate about matters of high importance. However, the court will not permit a campaign of vilification in the media about individual persons who are the subject of trial proceedings.”

By getting caught in the vortex of Wilkinson’s irresponsible Logies speech, Patrick’s book will stand as a record of a period in Australian politics when balance was lost, when revenge triumphed over virtue in public life.

There is an apocryphal story doing the rounds of the eastern suburbs of Sydney that a bookstore not far from Malcolm Turnbull’s home in swank Point Piper has put Aaron Patrick’s new book, Ego: Malcolm Turnbull and the Liberal Party’s Civil War, out of sight to spare the feelings of Australia’s fleeting first couple should they wander in to browse for books. This is untrue. A visit to the store this week revealed that this book, about the damage wrought by Turnbull’s attachment to revenge politics, is displayed in clear sight.