Inside Albanese and Kishida’s unprecedented pushback against China

It’s not a military alliance, nor a peace treaty. But new declaration does use language almost identical to Australia’s pact with the US.

This is in the face of unprecedented Chinese assertiveness and unprecedented Japanese and Australian pushback.

In an exclusive interview with Inquirer on the eve of his Perth summit with Albanese, Kishida hailed Japan and Australia as “the core of a partnership of like-minded countries in the Indo-Pacific”.

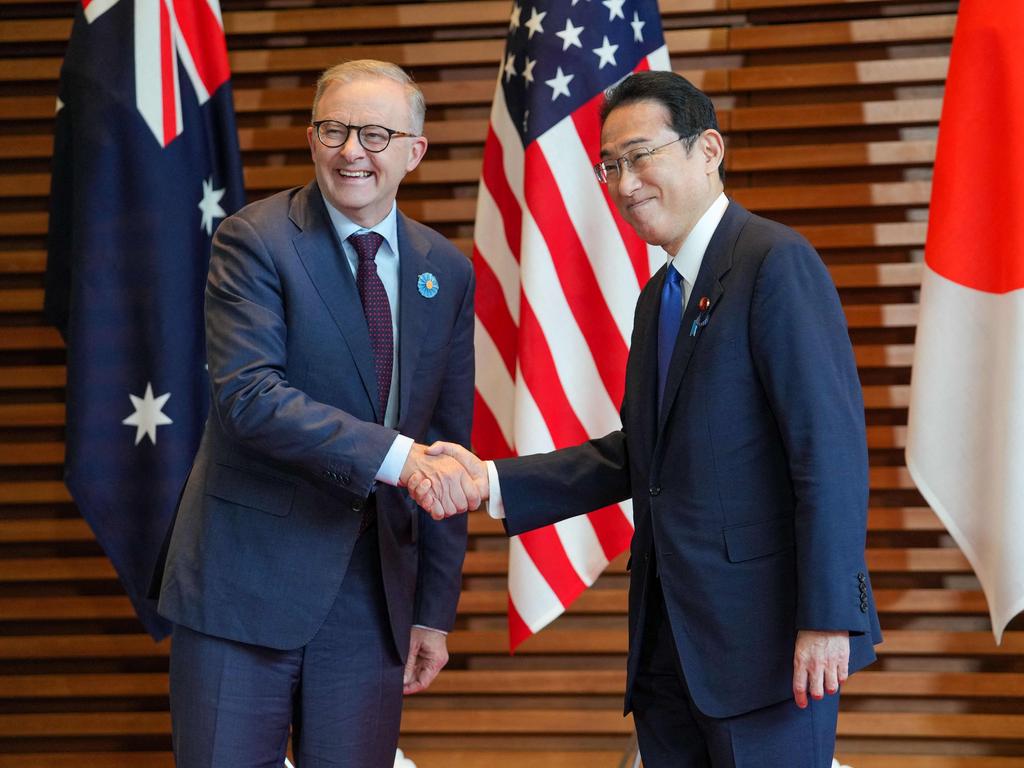

Kishida arrived in Perth on Friday night for a Saturday full of meetings with Albanese, as well as with West Australian Premier Mark McGowan and a number of Australian businesses. The visit is short because it is extremely difficult for Japanese prime ministers to travel abroad while the Diet, the Japanese parliament, is sitting. The visit will constitute the formal annual leaders’ meeting.

Kishida said Japan and Australia “share basic values” and he wants to take the relationship “to a new level” across three domains: security and defence co-operation, the promotion of a free and open Indo-Pacific, and resource and energy co-operation.

In remarkably frank and hard-hitting comments, the Japanese leader condemned Chinese military actions in the region, especially near Japan, and pledged Tokyo would fight to defend its territory and its interests.

“Unilateral attempts by China to change the status quo in the East and South China Seas, as well as the expansion and increased vigour of its military activities in the vicinity of Japan, are of serious concern to the security of the region which includes Japan as well as to global security,” Kishida said.

He was defiant in the face of what he sees as Beijing’s attempted coercion: “Japan intends to resolutely and comprehensively defend our territory, territorial waters and territorial airspace including the Senkaku Islands, and to uphold a free and open international order with the US-Japan alliance forming the cornerstone of our peace and stability. We will firmly maintain and assert Japan’s position and strongly request that China take responsible actions.”

On Saturday, Kishida and Albanese signed a new Joint Declaration on Security Co-operation. This is much more than an update of the 2007 declaration signed by then prime ministers Shinzo Abe and John Howard. That was mainly concerned with terrorism, nuclear non-proliferation and North Korea. This new declaration is concerned with building deterrence and strength in the face of Chinese military assertiveness. It is by far the most ambitious and consequential security agreement between the two nations so far.

The new declaration is not a military alliance, nor is it a peace treaty. But it uses language almost identical to Australia’s ANZUS alliance treaty with the US. It will commit Australia and Japan to consult each other on contingencies that affect each others’ security, and consult on responses to such contingencies. That language is almost an exact reproduction of the formal provisions of the ANZUS treaty, and no one in the region will miss the connection.

Beijing is sure to campaign diplomatically against the declaration, just as it complained in 2007, and just as it campaigns against the AUKUS agreement involving the US, Australia and the UK.

Kishida also condemned, in the toughest language, Beijing’s actions in relation to Taiwan: “A series of military activities by China in the vicinity of Taiwan in August, in particular the launch of ballistic missiles into the seas adjacent to Japan including into our exclusive economic zones, presented a grave concern to the security of Japan and the safety of our citizens.

“We strongly condemned and objected to these actions by China, and urged China to immediately cease its military exercises which were seriously impacting on the peace and stability of the international community.”

In written answers to questions, Kishida said Japan and Australia, as well as G7 countries, shared the same position on Taiwan, and expected that the issue of Taiwan’s relations with Beijing would be settled peacefully.

For his part, Albanese said during the days preceding Kishida’s arrival that Japan is one of Australia’s closes friends and partners.

Earlier this year the Morrison government signed a Reciprocal Access Agreement which allows the armed forces of both nations to train in each other’s territory and to enhance joint exercises.

Albanese said: “This visit provides the opportunity for Australia to further deepen its relationship with Japan … Discussions between leaders will look to strengthen the defence and security partnership, and will consider next steps to implement the Reciprocal Access Agreement which will enhance the ability of defence forces to operate and exercise together.”

Albanese chose to invite his Japanese counterpart to visit Perth, partly to emphasise the growing strategic partnership between Australia and Japan in critical minerals, and the resources and food trade generally. The two leaders will sign a memorandum of understanding on critical minerals co-operation. Next year Albanese will host a summit of the Quad, involving the leaders of the US, Australia, Japan and India, on the east coast of Australia.

Tokyo views Australia as a critically important and reliable supplier of natural resources and food to Japan. Kishida told Inquirer: “Japan highly appreciates Australia’s role as a stable supplier of resources and a trusted destination for investment. Furthermore, co-operation on decarbonisation … is a new frontier for the economic partnership.”

Well-informed sources suggest the Japanese have been a little spooked by some of the debate around Australian gas production and the need to priorities domestic customers over longstanding export customers like Japan, as well as some of the hostility to such resources projects in Australia.

“The export of resources and energy in the form of coal, iron ore and LNG from Australia to Japan, and the investment in those sectors from Japan to Australia, have underpinned the economic relationship between our two countries,” Kishida said.

He will seek a personal assurance from Albanese about the reliability of Australian gas exports to Japan. For his part, Albanese will assure Kishida Australia will not be interrupting long-term gas contracts with Japan. Historically, Japan has strategically relied on Australia for energy security.

This is at least the fourth meeting between the two leaders. Albanese went to Japan for a summit meeting of the Quadrilateral Dialogue (Australia, Japan, the US and India) almost the minute he was elected. He then met Kishida again at the NATO summit in Spain, where they had a series of meetings, and saw him again when he visited Japan for Abe’s funeral.

Kishida is a former foreign minister and speaks English well. Officials and diplomatic observers say the two men get on and interact productively and in a relaxed fashion in meetings. Kishida is not currently enjoying great popularity in Japan but his ruling Liberal Democratic Party remains dominant and he has extended the strategic policy and outlook of the late Abe, who was a great friend of Australia and a profoundly important champion of the US alliance system in Asia.

Kishida wants his visit, and the new Joint Security Declaration, to “outline the direction for Japan-Australia security relations for the next decade”.

Japan’s ambassador to Australia, the highly regarded Shingo Yamagami, was quoted in interviews in the lead-up to his Prime Minister’s visit saying explicitly that the new situation in the South China Sea and in the Taiwan Strait required Japan and Australia to upgrade defence co-operation “in order to increase deterrence”.

In his interview, Kishida was both ambitious and constrained about the Quad. He said: “The Quad is not a framework for security co-operation. It is a framework for the promotion of a wide range of practical co-operation aimed at realising a free and open Indo-Pacific. Japan, together with Australia, intends to provide leadership for initiatives in our region such as the Quad, and to strengthen co-ordination on a variety of issues including co-operation with Pacific Island nations.”

Kishida also expressed his support for Britain joining the Trans Pacific Partnership free-trade deal. Both Tokyo and Canberra oppose Beijing’s bid to join the TPP. For Canberra it is inconceivable that it could countenance Beijing joining the TPP while it still has trade embargoes against a number of Australian exports.

However, Canberra’s position goes beyond these specific trade measures Beijing takes against Australia. As Kishida says, the TPP is partly designed to enhance reliability of supply lines in crucial products. Beijing has shown a disturbing willingness to disrupt supply to Japan, Australia and other nations for political reasons. The domestic politics of the US make it impossible for Washington to join the TPP at the moment. It would not be remotely in either Tokyo or Canberra’s interests to have China join the TPP while the US remains on the outside.

Kishida is also greatly exercised about the dangers of Russia’s aggression in Ukraine leading to the use of a nuclear weapon. He also foreshadows the possibility of North Korea conducting another nuclear test.

On Russia, Kishida expressed views very much in strategic alignment with those of Albanese and the US-led Western world. He said: “Russia’s aggression against Ukraine is a threat to the very foundation of the international order. Amid this, threats to use nuclear weapons have contributed to worldwide concern that yet another catastrophe resulting from nuclear weapon use is a possibility.

“We should never tolerate the threat of the use of nuclear weapons by Russia, let alone the use of nuclear weapons. We must ensure that Nagasaki remains the last place to ever suffer an atomic bombing.”

Kishida is also concerned about recent North Korean missile activity: “As for North Korea, its repeated actions, including its launch of a ballistic missile that flew over Japan on October 4, present a serious and imminent threat to the national security of Japan and threaten the peace and security of the region and the international community. Such actions are unacceptable. North Korea may engage in further provocative actions in the future, including another nuclear test.”

The fact the Prime Minister of Japan should speak so frankly to the Australian people, through a newspaper interview, of the grave strategic threats in our region and internationally, posed by China, Russia and North Korea, should serve to underline to our nation how difficult and dangerous strategic circumstances have become.

Kishida has a wide understanding of the breadth of the Australia Japan relationship, and he and Mr Albanese will pursue much common activity in areas of Green and decarbonising technology, as well as the traditional resources trade.

But there is no doubt the urgency in the relationship comes from the darkly complex security environment.

Dr Mike Green, the head of the US Studies Centre at Sydney University, is a former Asia director at the US National Security Council and the foremost American expert on Japanese strategic policy.

Green believes Japan, Australia and South Korea are the US’s three most important allies in Asia, and that Japan and Australia have both become increasingly important. He also believes Canberra and Tokyo are growing into much more intimate security partners.

“It’s striking how close Japanese and Australian views of China are,” he tells me.

“The Japanese public has been at this point for 10 or 15 years; the Australian public has arrived at this point over the last couple of years. Because (China’s leader) Xi Jinping won’t soften Beijing’s policies, this is unlikely to change.

“Xi has long argued that this is essentially a bipolar region and the US needs to make compromises to accommodate China’s rising power. What the Albanese/Kishida summit shows is that this is a multi-polar region and Japan and Australia have a major influence on the region.”

In a major research project, the US Studies Centre has recently commissioned extensive public opinion surveys in the US, Japan and Australia to gauge sentiment on strategic issues.

The results, which indicate a growing strategic alignment among the three countries, will be publicly released at the end of the month, but Green shared some of the highlights with me.

“Two things in particular indicate the alignment,” he said. “Between 52 to 55 per cent of US, Japan and Australian publics say China is more harmful than helpful in Asia. And a majority of Japanese and Australians don’t want the US to change policy on China.

“As well, a plurality of respondents in Japan and Australia said their countries should send forces to join the US if it takes military action on Taiwan. That shows a significant consolidation and alignment of concern about China in all three countries and a willingness to push back and decouple from China over hi-tech.”

The surveys also showed strong support for the AUKUS agreement in all three countries, even though Japan is not a member of AUKUS. There is significant US and Australian support for Japan to be part of AUKUS.

Green also reports that the standing of Australia in Japan is very high. Enhanced security co-operation with Australia enjoys strong support in Japan.

The relationship with Japan has been the most significant, remarkable and sustained Australia has had with any Asian nation. Singapore rivals it perhaps in some ways for intimacy but not for overall importance.

After all the bitterness of World War II, it was visionary leadership in both Japan and Australia which led in 1957 to the historic Japan Australia Commerce Treaty, pursued by the vastly under-rated – in strategic affairs – Menzies government in the vastly under-rated decade of the 1950s, in which Australia became a fully modern nation and set the basis for the next 70 years and more of its strategic and global outlook.

That commerce agreement, between two nations, which had recently been ferocious enemies, was critical in bringing Japan back into the front line of nations and ultimately of global powers. Now, new leaders, Kishida and Albanese, face a crisis and an opportunity just as great, and perhaps much more consequential, than their forebears in the 1950s.

Kishida’s strong words and commitments, and the two nations’ new security declaration, as well as their wider trade and environmental agendas, suggest they just might meet their rendezvous with history.

Two unlikely leaders, Japan’s Fumio Kishida and Australia’s Anthony Albanese, will bring their two nations into the closest security, political and economic partnership they have ever attempted.