Indigenous children deserve voice to build better future

Grassroots perspective would help break down barriers preventing improvements in the lives of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

“That bastard had blue eyes.”

These are some of the last words my grandpa said to me.

“The bastard that took me away. We were at Hamilton Downs and Dad was away mustering. Mum had just made a cup of tea. There was someone at the door. Mum dropped her pannikin, I could hear her crying. That bastard pulled me out from behind my mother. I was trying to hold on to her leg, and Mum just kept crying, ‘please, no’. Why did he do that, Catherine? I cried for my mother every night.”

He told me this story from his hospital bed, as an old man. It is a painful memory, to me as it was to my grandpa. But he needed to give me his story so others could hear it, too, and hopefully understand.

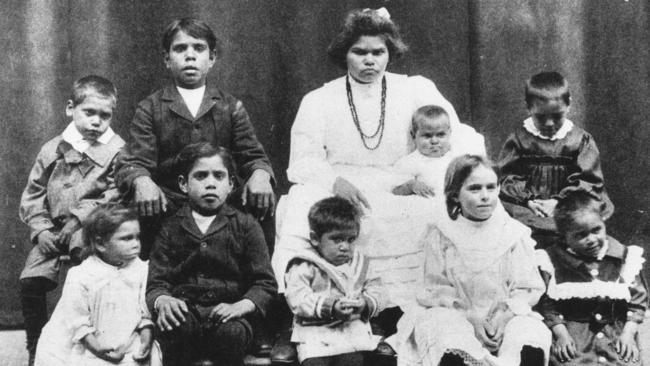

My grandpa was a worker. He and my nana, who was a very important lore woman, who held the songs and stories of her Tjukurpa, would be measured as successful. They raised a family, owned a cattle station, my nana was a renowned artist. They achieved all this while carrying an immense amount of pain and trauma. That’s not what they named it back then but that’s what it was. My grandparents would share stories of the “rifle times”, of children being hidden under logs and blankets to hide from the white men who would shoot them or snatch them.

Nana would also share stories of the great serpents, revered by Anangu. Wanampi the Rainbow Serpent, bringer of rain and essential for life. As children we knew, with both pride and fear, that we belonged to the Kunya, protector of children, giver of water. But the serpents can also take life, they have a duality.

Just as a person can be seen as a success, they can still carry a load of pain and trauma, not only from their own experience but reaching back to the experiences of their parents, their parents’ parents and even further. My mother has a legal degree, my brothers are doctors, my sister works in the banking industry, one of my cousins is a senator. I’m very proud of my family’s achievements but, believe me, intergenerational trauma still figures large in our lives. This is why I made the decision to work in the field of child wellbeing and development. To change the systems, acknowledge the past and build a future where we can break the cycles of trauma.

To deny the impacts of colonisation on a people who have been dispossessed of their lands, their culture, their identity, who were hunted, had their women and children stolen, defies common sense.

To deny that this has resulted in intergenerational trauma is a denial of science, of fact. The evidence is there.

A staggering 65.7 per cent of First Nations children started school developmentally vulnerable in 2021, which would be a damning statistic in its own right but is made only more compelling when one realises that this was a decrease from the 2018 levels.

More and more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are being removed from families and put into out-of-home care. In one state, this has now been reported as hitting six generations of removal.

This is not because they are not loved. No one aspires to be homeless, no one aspires to be jobless, no one aspires to live in poverty, but these are some of the underlying drivers that result in child removal. This is a symptom of systems over which we have no influence. Policies stripped our communities of jobs. Policies invest in outsourcing services instead of developing remote and regional areas. Policy drives millions and millions of dollars away from community-led development and into centralised administration.

This disempowering of people and communities traps families in systems that were designed for us but without us.

We are not making meaningful progress – we are moving backward.

In recent months there have been a host of reports, from the Productivity Commission to the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission and royal commissions, detailing how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children continue to fall through the cracks.

I’ve heard many ask: How would a voice to parliament change these realities, what practical purpose would it serve?

My answer is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have more than 65,000 years of successfully raising children. We would not be the world’s oldest living culture if we did not care for and cherish our babies.

An advisory body, informed by perspectives from the grassroots, from our communities, would help break down the barriers that are preventing improvements in life outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

A voice would help inform the government about the adverse consequences and impacts of policies such as the Northern Territory Intervention, an initiative dreamt up in Canberra, estimated to have cost more than $1bn and labelled Australia’s most expensive political stunt. A voice would be able to speak out about the folly of this failed approach. Let’s be clear: under the intervention life outcomes got worse.

A voice would be heard and consulted about the more than $500m cut from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander services in 2014. On top of this more than $80m was cut from Aboriginal child and family centres, funding that has never been reinstated.

A voice would allow us to have a say in our own affairs, to acknowledge that we have the solutions that can make a better future for our children, where the odds don’t fall more in favour of a young Aboriginal person entering jail rather than university.

In a few weeks we all have a once-in-a-generation opportunity. We can secure a different future for our children, to transform the way governments work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

Our children deserve no less than Yes.

Catherine Liddle, an Arrernte/Luritja woman from central Australia, is chief executive of SNAICC – National Voice for Our Children, the peak body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.