India’s lesson is this virus is just getting started

We shouldn’t demonise India. This virus has embarrassed nearly every government in the world and shows Covid still has a long way to run.

As one Indian famously observed: they die agonisingly, like fish out of water, gasping for breath.

Australia must help India in every way we can, urgently, on humanitarian and geo-strategic grounds. But we shouldn’t demonise India. This virus has embarrassed nearly every government in the world at one point or another.

Trying to understand where we are with the virus globally is challenging because there are so many cross currents, so many things happening that we never predicted, some good, some terrible.

Health Minister Greg Hunt, who has performed very effectively throughout this crisis, has as good a handle on the situation as any politician. He tells Inquirer: “We know we don’t know everything (about the virus). “But we do know that, one, it’s got a long way to go, and two, vaccination does work.

“Lockdowns, vaccines and some degree of immunity (in countries which have had large-scale infections) can work together to bring rates down. But you can also see how it can get away.”

Hunt’s comments are the beginning of wisdom because they make two uncomfortable admissions: we don’t know everything about the virus, and the virus still has a long way to run.

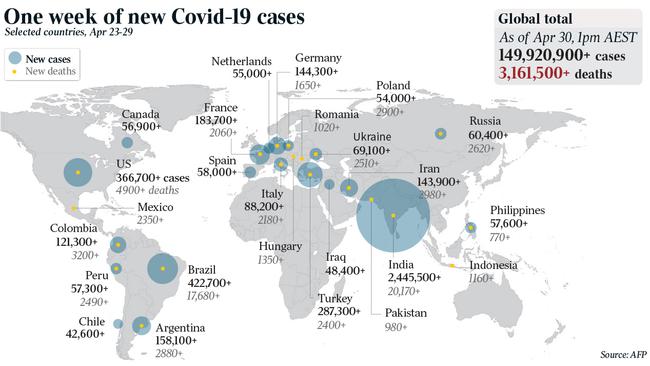

Let’s review some stark numbers.

According to figures released by the national cabinet on Friday, there have been 150 million cases of COVID-19 infections and more than three million deaths. In just one day this week, there were nearly 900,000 new cases and more than 14,000 deaths globally.

National cabinet didn’t say so, but these figures massively understate the number of COVID deaths. Today, people are dying all over India who cannot get to hospital and whose deaths won’t be recorded as related to COVID. That has happened in many, many countries.

We are now about 16 months into the pandemic. Infection rates around the world have never been higher and new mutations are proving extremely tricky to deal with.

Trying to get perspective on the trends and the meaning of all this information is difficult.

When Australia first became really conscious of this pandemic a little over 12 months ago, like many journalists, I spoke to as many experts as I could about what was going on, what it meant and how it would play out. How would it end, I asked a senior government official.

All these infections have burned themselves out, he told me.

That hasn’t happened yet.

One senior medical figure of the highest quality assured me that coronaviruses didn’t mutate like the flu virus. If we got a vaccine, the virus wouldn’t mutate away from the vaccine like the flu virus does.

Alas, the virus hadn’t read the right text book. It’s mutating its head off. None of the experts I spoke to anticipated anything like “long COVID”, the often debilitating syndrome that afflicts many people who get the virus and recover. In Britain, more than 1 per cent of COVID recoverees have suffered from long COVID for more than three months. This figure is somewhat higher among working-age people who recover from the virus.

Some half a million Brits have had long COVID for more than six months. The Economist magazine speculates, pretty gloomily, that their chances of full recovery are slim.

Other people told me early on there was no effective aerosol transmission, which would make the virus much worse. We now know there is extensive aerosol transmission.

Those Australian experts who were wrong about the virus burning itself out, or how much it could mutate, or who didn’t anticipate long COVID, were not remotely incompetent. They are the highest-quality people, working as hard as they can and operating at the limit of human knowledge. The problem is that human knowledge of the virus still has pretty severe limits.

I fully get it that the virus is not literally a sentient being. But metaphorically, or just through the bias of all living organisms to survive and reproduce, it is proving itself cunning, adaptable, unpredictable and brilliantly opportunistic.

So far Australia has done very well throughout this virus. My patriotism does not constrain me at all from castigating either the government or the nation when something goes wrong. But a simple empirical test establishes the point — there is no country in the world, not one, where you would rather have spent the virus so far.

But past success doesn’t guarantee future success, as India is showing today, and as many other nations have shown. Australia’s success has come in large part through the contemporary application of medieval plague policy, keeping the virus out and isolating those who are infected.

Now, the hyper modern element of our policy — vaccination — is moving forward. About 2.25 million people have been vaccinated. The Morrison government has sensibly given up targets, because there are so many uncontrollable and uncertain factors. But there is a widespread belief in official Australia that everyone in the nation who wants a jab will have got at least their first vaccination by year’s end, with some millions having completed the two doses. The government, and Australian vaccine manufacturers, are already working on the booster shot strategy which will almost certainly be necessary for late 2022.

But so much of this is still genuinely uncertain. Anyone who claims they know what the virus will do next year needs sympathetic counselling or reference to the Fraud Squad. The world’s hope remains vaccines.

A few days ago, the world passed the one billion mark for vaccines delivered into people’s arms. That doesn’t mean one billion people have been vaccinated. A lot of people have had two doses. It is also the case that fewer than 1 per cent of those vaccines have been given to people in poor countries.

The virus is separating the world pretty savagely — rich and poor. The virus itself doesn’t discriminate. But rich countries can buy or manufacture vaccines, they can afford the non-pharmacological interventions (social distancing), and they can treat people who do get sick effectively in good hospitals, which massively reduces the mortality rate.

So rich countries like the US and Britain, even if they greatly mismanaged things initially, have been able to combine effective lockdowns, social distancing and mask wearing with rapid vaccination and good-quality hospitals, as well as that natural immunity which comes from so many of their citizens having had the virus. This has taken a fearsome toll in deaths — nearly 600,000 in the US and nearly 130,00 in the UK. Nonetheless, so many people having had the virus means there are a certain number of people who can’t get it again. Thus, combined with vaccination programs, COVID infection rates in both the US and Britain have fallen sharply. But these are two of the richest countries in the world, which have devoted a massive amount of money to researching, producing and buying vaccines.

This week saw another milestone. Brazil became the first nation after the US to register more than 400,000 COVID deaths. That is a sign of the new and deadly trend in COVID. It is switching from first world countries to developing countries, but they will have much less capacity to vaccinate en masse and to take all the other necessary measures.

When the virus first came round, once it got out of Wuhan, it hit first world countries harder than developing countries. There were a lot of reasons for this. The first version of the virus hit older people much more often than younger people. Rich, Western nations had older populations. Also, the virus spread through international travel. Citizens in rich countries are globe-trotters. Annual holidays abroad, or numerous international business trips per year, are almost a sacred human right for much of the Western middle class. And then people in Western nations are typically much more obese than people in poorer nations and thus got much sicker with COVID.

So the first crises were in northern Italy and New York, two of the richest regions in the world. Both health systems were nearly overwhelmed. That New York didn’t use some of its specialist facilities set up just for COVID doesn’t mean the system wasn’t overwhelmed. New York shunting infected old people out of hospital and back to aged-care facilities, where they died in huge numbers, was a terrible decision born out of the stress and over crowding of the hospital system at the height of the crisis.

But now the virus is moving decisively into developing countries, such as India and Brazil and Bangladesh and the Philippines. In time, let me make this one doleful prediction, it’s likely to do its worst in Africa too.

Why has this happened?

There are several causes and one caveat. The caveat is that we don’t quite know for sure exactly why it has happened. But we do know that India is being hit both by the British variant, and by the Indian double mutant variant. There is still a lot of scientific uncertainty about the latter especially. But it seems likely that both are more infectious than the original virus and are more inclined to attack young people.

At the same time, India relaxed social distancing policies before this second wave came crushing down. A number of its political leaders, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi and indeed the Health Minister, seemed to think either that India was immune to the virus or had somehow “defeated” it.

And so it went from cautious, careful and successful to complacent, careless and now living in the midst of disaster. But no country has defeated the virus, at least not yet. The virus doesn’t accept defeat. India thought it had got past the worst and allowed huge political rallies and religious festivals. While we’ve all made mistakes, no comment in the whole virus saga has ever been dumber, whether coming from a politician or a commentator or anyone else, than to say the worst of the virus has passed. India, thinking it had weathered its crisis and failing to anticipate the nightmare a second wave would bring, did not accelerate either vaccine production or medical oxygen production. Now it is having to gobble up all industrial oxygen production and try at breakneck speed to ramp up medical oxygen production.

All this is having geo-strategic consequences. Indian prestige and the sense that it is an emerging superpower has been dealt a terrible blow. Hopefully, it’s a temporary blow. The world, especially Australia, is coming to rely on India as a central element of global governance, international economy and geo-strategic stability.

China and Russia have prospered through vaccine diplomacy. Russia has supplied, or will supply, 70 countries in Asia, eastern Europe and Latin America with vaccines. China will similarly supply 90 countries. The Chinese and Russian vaccines are less effective, and less fully tested, than the Western vaccines, but for poor countries they are better than nothing — although in some parts of the world, especially Africa, a nearly insane suspicion of vaccines is keeping jab rates low. This may be tragic for Africa.

But here’s the big sleeper. Some virus mutations are showing a modest ability to break through vaccinations. Vaccines are overwhelmingly effective in shielding you from serious illness, hospitalisation and death. It’s less clear if they prevent secondary transmission.

But the bigger the total number of infections in the world — and the total number is rising rapidly — the bigger the virus’s potential for mutation. And this virus is full of surprises. There is absolutely no guarantee that it won’t, in time, find a way around or through our vaccines.

This virus may change the international way of life permanently. As Hunt observes, we don’t know everything, and it’s got a long way to run.

The scenes in India are heart-rending. Hospitals are full. Oxygen is exhausted. People are dying on the pavements outside clinics, unable to gain admission.