Incidents and accidents have been changing the course of music for years

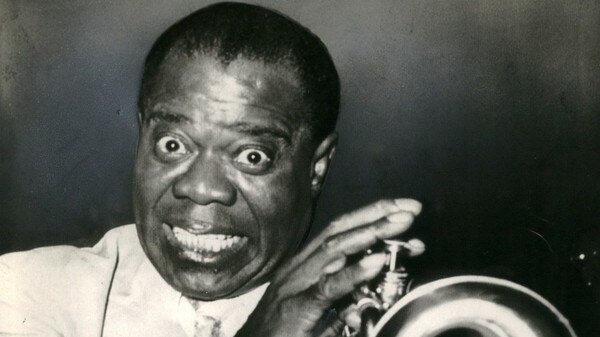

Louis Armstrong forgot his words and popularised scat, Dave Davies slashed his speaker and gave birth to metal: these are the mistakes that changed music.

Science fiction writer and academic Isaac Asimov insisted that right and wrong “are fuzzy concepts” and perhaps nowhere is that more obvious than when people make music.

Music revels in the knotty imperfections of the human hand. No finger sliding up any guitar string – not even if attached to the hand of Melbourne’s John Williams, perhaps the world’s supreme instrumentalist – lands at precisely the same spot twice. No passage of piano notes ever comes in at the same duration. No drummer strikes any part of his kit with exactly the same momentum and at the same angle twice.

These differences may appear to be imperceptible, but even the untrained ear – and certainly the brain to which it sends messages – discerns quite subtle, unintended nuance. And that is why music created by machines, or, more often these days, “corrected” by digital technology such as Auto-Tune, is mostly obvious.

The proliferation of this technology and these devices’ unerring capacity to produce and reproduce sounds with spiritless precision are why today’s popular music only sometimes takes unexpected strides in a new direction, and rarely since the mid-1990s. Auto-Tune became available in 1997 and soon took over the recording world. It’s no coincidence.

We have been familiar with music changing course through an unending series of incidents and accidents. And thank God for them. Since February 26, 1926, during a Louis Armstrong recording session, to extreme metal outfit Venom in more recent times, and beyond, music’s mishaps have shaped what we love listening to.

When Satchmo (Armstrong was at first nicknamed Satchel Mouth; over time this contracted) recorded Boyd Atkins’s song Heebie Jeebies in Chicago early in 1926, he was almost certainly singing into a horn that collected the sounds of all band members and instrumentalists and cut it directly to a wax disc. (Microphones had been invented the year before, but were hardly common). Armstrong, his penetrating trumpet playing already legendary, regularly sat about two metres back from the pack. On the day his Hot Five came to record Boyd’s song, the words to which he had not yet memorised, he dropped the lyric sheet. With no one beside him to pick it up, from the 1.48 minute mark he vocalised sounds with “words” that fit the melody – and scat was popularised. Plenty of singers had been scatting at live shows, but it had never been a recording technique.

Soon scatting was mainstream and even Bing Crosby, America’s favourite singer, scatted across a few songs. Wordless vocals had become another instrument. By 1961, Ella Fitzgerald had won two Grammy Awards for her legendary scat vocals on Mack the Knife recorded during a live concert in Berlin. Even the Doors’ Jim Morrison famously scatted the middle section of the 1969 live version of Roadhouse Blues, but then a few dozen Budweisers will do that.

Perhaps the accident that changed music most happened late in 1960 when Marty Robbins recorded one of his biggest hits, Don’t Worry. On guitar was Nashville gun Grady Martin, but he was none too pleased. A faulty fuse in an amplifier distorted his instrument’s sound (there have been other explanations, but these are the facts according to Jordanaires singer Gordon Stoker who was at the session and spoke about it not long before he died in 2013).

“Grady said there was a tube blown out in his amplifier,” said Stoker. “He wanted to get a different amp and Don Law (the Englishman producing that day) said, ‘I like the way it sounded, old boy’. We were standing there and I know it was in his amp.”

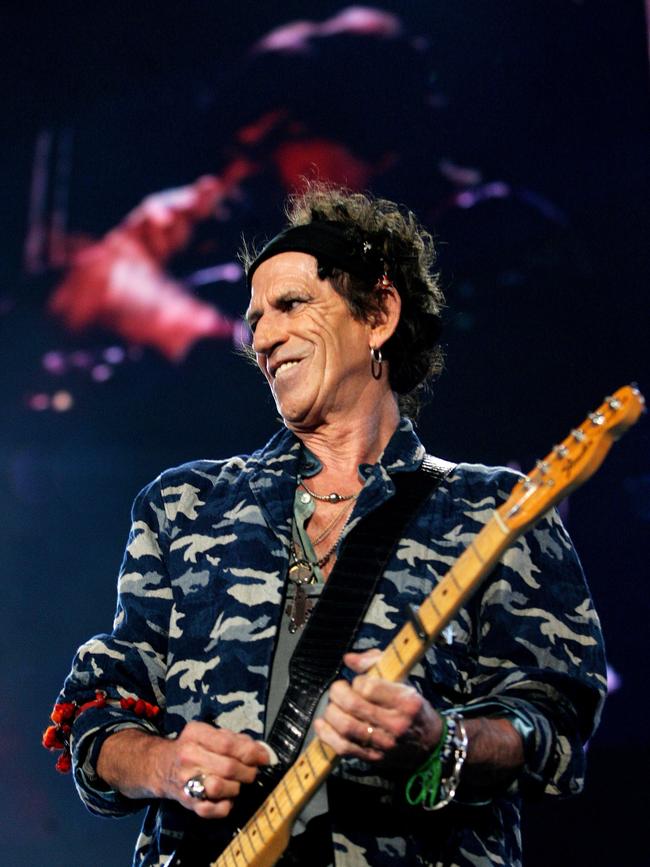

Martin must have come around to the new sound too; by the end of the year he had recorded a corny instrumental using it, appropriately titled The Fuzz. By the following year bands were seeking equipment to mimic the fuzzy tones and the Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz Tone plug-in device was born. The sound remained a gimmick until the Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards bought one and used it on (Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, which topped charts around the world and popularised intended distortion. And after Satisfaction, bands no longer played rock ’n’ roll. It was just rock.

The same week that the Stones’ single came out, Jeff Beck’s fuzzy lead guitar dominated the Yardbirds’ Heart Full of Soul, and the sound would soon be a major part of rock, including Jimi Hendrix’s Foxy Lady, the Guess Who’s American Woman and Iron Butterfly’s In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida.

English band Venom did not intend to forge a new direction for heavy metal music when it released its first single 40 years ago. When the three musicians recorded their barbaric yawp in a low-fi studio in Wallsend, outside Newcastle-upon-Tyne, they proved incompetent. Anthony “Abaddon” Bray, the drummer, did not realise the snare was the most important part of his kit and ignored it entirely, pounding out a rhythm on the toms. That very amateurism, combined with the poor recording equipment, meant the song In League With Satan sounded like no metal record before it. From that track sprang all the metal variants that are grouped under the heading “extreme metal”. By not knowing what they were doing, Venom had inadvertently invented a genre.

The first hints of metal, some argue, had been born in 1964 when Dave Davies of the Kinks inadvertently invented yet another distorted guitar sound by taking a razor blade to the speaker cone of his amplifier in frustration: the damaged speaker made his guitar suddenly sound unhinged. A few years later Black Sabbath’s lead guitarist, Tony Iommi, lost two fingertips on his right hand in an industrial accident the day before he was to start with the band. To continue playing, he shaped false tips out of plastic, but found he struggled to bend the strings. Only by downtuning his guitar to make the strings loose could he manipulate them, and so the ominous, deep sound that bands still produce today was created.

The invention of dub music in Jamaica in the late 1960s was an accident, too – the result of human error. A studio engineer forgot to add the vocal track to a mix that King Tubby, another engineer, was assembling. When the instrumental version was played at a dance the next weekend, the crowd loved it. Bunny Lee, a reggae producer, later recalled telling King Tubby about the reaction of the partygoers: “Tubbs, the mistake we made was a serious joke. It mash up Spanish Town! The people went wild … It played about 20 times.”

When new technology has forged genres, it has not always been by design. Hip-hop would have been impossible without the Technics SL-1200 turntable. Rather than being propelled by a belt, it used a motor and so reached playing speed almost immediately. This made the techniques employed by hip-hop DJs, such as scratching, possible. The pitch-control slider allowed DJs to slow down or speed up records, too, which made beat-matching feasible; different records could be bled seamlessly into one another. None of that had been foreseen by the turntable’s designer, Shuichi Obata, in 1979.

Hip-hop and electronic dance music owed further leaps to a technological mistake: the distinctive “sizzling” sound of the Roland TR-808 drum machine – the foundational sound of electronic music in the 1980s – came from a defective transistor. Once transistor manufacturing standards improved, the imperfect ones disappeared and Roland could no longer find them. In 1983, because there were no faulty transistors left, Roland had to stop building the TR-808, after a run of just 12,000.

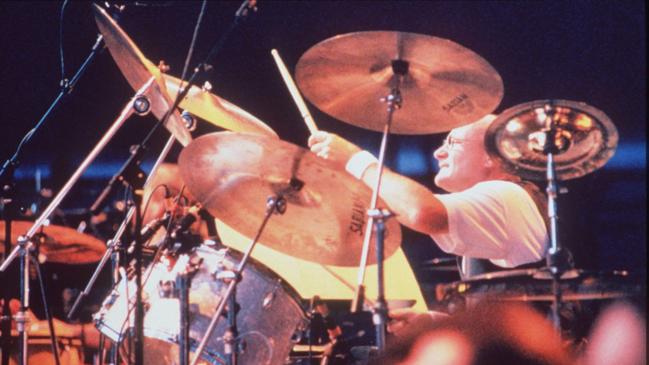

Anyone with ears in the 1980s became very familiar with another studio accident that created what is known as the “gated reverb” drum sound. It was used to great effect on Phil Collins’s In the Air Tonight, Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the USA, David Bowie’s Let’s Dance, and Kate Bush’s Running Up That Hill. And then, it seemed, on every other record until January 1, 1990.

It came about when Collins was playing on former Genesis bandmate Peter Gabriel’s third solo album late in 1979. The producer, Hugh Padgham, left a talkback mic – used to speak to the studio musicians by those at the console outside – on and it recorded Collins playing on the song Intruder. The mic was heavily compressed and the sound passed through what is known as a noise gate. Padgham and Collins each saw the potential in this and immediately started work on perfecting this serendipitous sound. Essentially, the drum sounds builds quickly – milliseconds really – to the maximum level and is then digitally cancelled. The suddenness of this sound, and its unnaturalness with no reverberations, is arresting. It seized the imagination of western rock music for years. You can still hear it today, but, mercifully, less often.

And then there is the backwards running tape, a phenomenon that John Lennon chanced on and the Beatles first used the following day when recording the 1966 song Rain. Lennon had taken reel-to-reel tapes of the day’s work home to review. Shortsighted, he spooled the tape on the wrong way and immediately heard himself sing Rain in reverse (the band’s producer George Martin always disputed this, but Lennon stuck to his guns). At the end of song the line “If the rain comes they run and hide their heads” plays backwards. For a year or two the band regularly recorded vocals and instruments backwards, sometimes with daft messages, a technique that became known as backmasking. It has been used ever since by artists as varied as Kiss, Iron Maiden, Pink Floyd, Prince, Journey and Oasis, sometimes to disguise very naughty lyrics indeed. Electric Light Orchestra did it more than a few times, and on the song Fire On High – the B side of 1975’s Sweet Talkin’ Woman in Australia – at the 27-second mark there is what appears to be gibberish, but backwards it clearly is “The music is reversible, but time is not. Turn back! Turn back! Turn back! Turn back!”

When the surviving Beatles recorded the comeback single Free as a Bird in 1995 – based on an unfinished Lennon song from 1977 – they returned to the habit. In its dying moments Lennon appears to say “Made by John Lennon”. When that moment is played backward he clearly states “Turned out nice again”.

Music aficionados often complain that there’s nowhere left for rock and pop to go. They need only wait for the next time a musician doesn’t know what they’re doing and, by mistake, makes a breakthrough. Perhaps right now, someone in a factory somewhere is putting faulty wiring into a computer and, somewhere down the line, someone else will realise that glitch will make a sound not heard before. A new style of music will be born.

Additional reporting:

The Economist

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout